An artist with an idyllic childhood might be as rare as a house with walls made of air, but both play a part in the story of architect John Lautner.

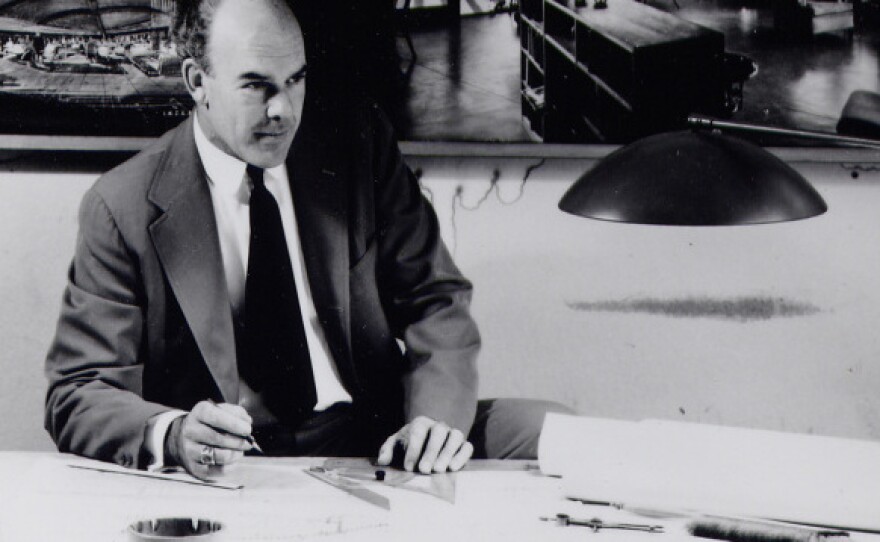

Lautner's homes have appeared in Hollywood movies, but the architect himself wasn't particularly well-known when he died in 1994. Still, in 2011 — the centennial year of Lautner's birth — his hometown of Marquette, Mich., has honored him with two exhibitions: one at Northern Michigan University's DeVos Art Museum and one at the Marquette Regional History Center.

The Marquette commemorations speak to Lautner's connection to the region. Before moving to Los Angeles, where he spent much of his adult life, Lautner had worked with famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright as a Taliesin Fellow. In the 2009 documentary Infinite Space, Lautner explains the shock of arriving in L.A. after growing up and working in the Midwest.

"It was so damned ugly I was physically sick for about a year," he says. "I'd been used to ... everything beautiful, and here everything's ugly. I couldn't imagine doing anything as ugly as Los Angeles."

'Cliff Dwellers' And 'The Big Lebowski'

Lautner tried to encourage deep respect for nature in everything he made; from his influential 1949 design of Googie's coffee shop in L.A. to the family houses Hollywood has used as bachelor pads in films like Diamonds Are Forever, A Single Man and The Big Lebowski.

The villain pornographer in that last cult classic lives in Lautner's Sheats-Goldstein House. He and The Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, negotiate a deal under a huge triangulated slab of concrete that serves as a roof while The Dude chills on a Lautner-designed sofa and rays of light dapple the living room through 750 drinking glasses that Lautner embedded in the ceiling. His desire was to recreate the rays of light that pierce through tree canopies in old growth forests, like the one he spent time in as a boy. Those experiences were central to his architecture.

"When I first started, I thought about the cliff dwellers and the nomads and what people really are, you know, psychologically and every other way," Lautner says in the documentary. "And they want to be free, but they want a little shelter."

Lautner's houses have cave-like areas that provide a sense of security. You feel grounded, and then, with your back to the shelter, he gives you hypnotic views of heaven, city, forest, ocean — any entity larger and more meaningful than a single-family home. Just look at the Elrod House in Palm Springs, which Lautner built with retractable windows around existing boulders on a hillside.

Wim de Wit heads the department of architecture and contemporary art at the Getty Research Institute, which holds Lautner's archives. He describes the Elrod House experience as unforgettable.

"You stand in the house; you see that huge structure around you with this concrete vault above you and rocks coming out of the mountain into the house," de Wit says. "And all of a sudden somebody [pushes] the button and the glass wall [opens] up. That is just an experience that I think everybody should have once in their life."

In Lautner houses, redwood walls swing open on hinges; curtains of air form walls that divide spaces; skylights open to the heavens; so-called "infinity pools" start in the house, flow under glass walls, outdoors and then seem to drop off the side of the earth.

Approaching 'Sublime'

Lautner's most famous house might be the Chemosphere in the Hollywood Hills, an eight-sided capsule on a pole that looks like it belongs in The Jetsons. The design was really just a low-cost way to build on a bad site without ruining the natural landscape — and, of course, to provide a nice view. The materials had to be hauled up the side of the hill, partly by the client himself. The process recalls Latuner's own experience as a boy back in Michigan, when he helped his parents build a house on a rock shelf overlooking Lake Superior. His mother, an artist, named the house Midgaard, Norse for "between heaven and Earth."

"To be at Midgaard, it's a little bit like you've been taken back in time," says Melissa Matuscak, director and curator of the DeVos Art Museum in Marquette. "When you stand out on the rock in front of Midgaard and you look over Lake Superior, you literally feel like you're floating over water. It's very quiet; it's very serene. I think you get very close to this idea of 'sublime.' I really do. I can't think of a whole lot of other places that I've felt such a powerful force of nature."

Matuscak says she wants the locals to appreciate John Lautner as well as the beauty that surrounds them, just like he did. Maybe they'll even feel Lautner's longing to be home.

"I like to think that when Lautner was designing these houses ... he was hoping to sort of recapture this boyhood wonder and feeling," Matuscak says, "gazing out into the landscape and sort of feeling like you were really joined between yourself and the landscape that you see."

Many owners of Lautner houses in Southern California say they've never felt as comfortable living anywhere else. Michael LaFetra has lived in a Lautner in Malibu for years.

"I would be lying if I said that I giggled every morning," he says. "But the truth is when you see the play of the wood and the concrete, inevitably by the time that I've walked down to have my first espresso I've at the very least smiled, if not giggled out loud."

With a house like that, it's hard not to want what he's having.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))