When it was time to create a new collection, Christian Dior had a ritual: He went to his garden and sat down among the flowers.

Fashion historian Florence Muller gathered drawings, photographs and paintings by Manet, Monet, Renoir and others for an exhibition on Dior and Impressionism, at the Dior Museum in Granville, the designer's hometown. Granville is a dreary little seaside town in Normandy, France, which these days is festooned with photos of roses in celebration of its native son.

Muller says the garden ritual served Dior from 1947, when he famously invented what was dubbed the New Look, until he died 10 years later, at age 52. An old photograph shows Dior, pudgy and bald (one wag said he "looked as if he were made of pink marzipan"), in his garden, finding inspiration. You can see him in real concentration, sitting at a little table, with a pond behind him — he's thinking and drawing, and creating.

"Each season he had to invent so many dresses, perhaps that's why he's holding his head," says Muller. "It's not so easy, you know, the work of a grand couturier."

When he was 15, Christian Dior helped his mother design their pretty garden in Granville. Up a winding seaside road, the Diors' pink house is a modest one.

"It's not a very important house," says Brigitte Richard, chief curator of the Dior Museum. "In fact, it's a house of a bourgeois family settled in Granville."

Dior's bourgeois father was a fertilizer manufacturer. (Handy, for gardening!)

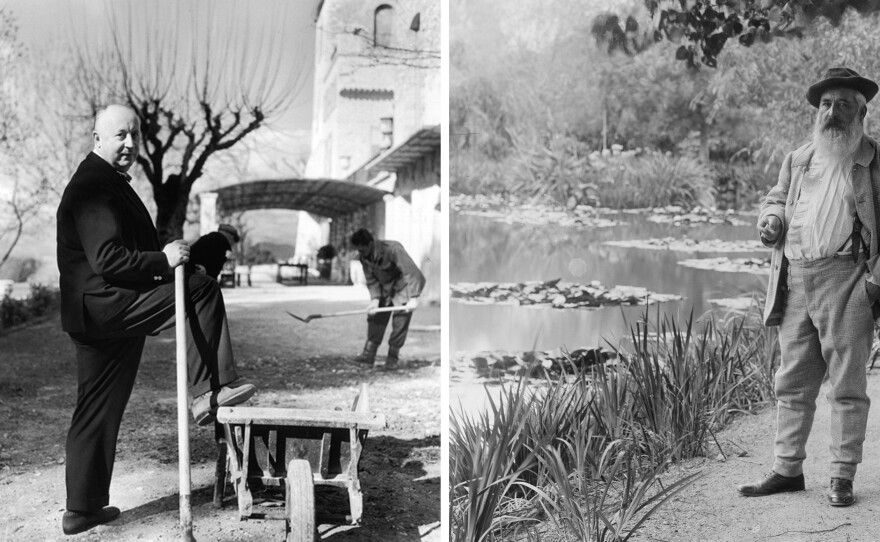

Like the designer, the artists of Impressionism were also inspired by flowers. Muller picked two photos to make the point.

"You have here the idea of painters in their garden," she explains. "Like Monet, of course, [a famous example of a] garden created by an artist. And on the left side, Christian Dior with his gardens that were also creations designed by him."

Dior stands in his gardens, in a suit and tie. Monet, in suspenders and soft hat, looks more relaxed. But both were flower lovers: Monet put gardens on his canvases; Dior put them on women. Dress collections named for flowers; fabrics patterned with roses, lily of the valley (his lucky flower, he said), embroidered bouquets; full, full, skirts that swirl like petals.

"Ha!" said Chanel, just a bit competitively. "Dior doesn't dress women. He upholsters them."

A strapless gown with a gauzy white skirt, once worn by Sarah Jessica Parker, is placed near a Degas ballet class. John Galliano designed the dress — he did the Dior line from the late 1990s to 2011. Other Dior designers include Yves St. Laurent, and these days Raf Simons.

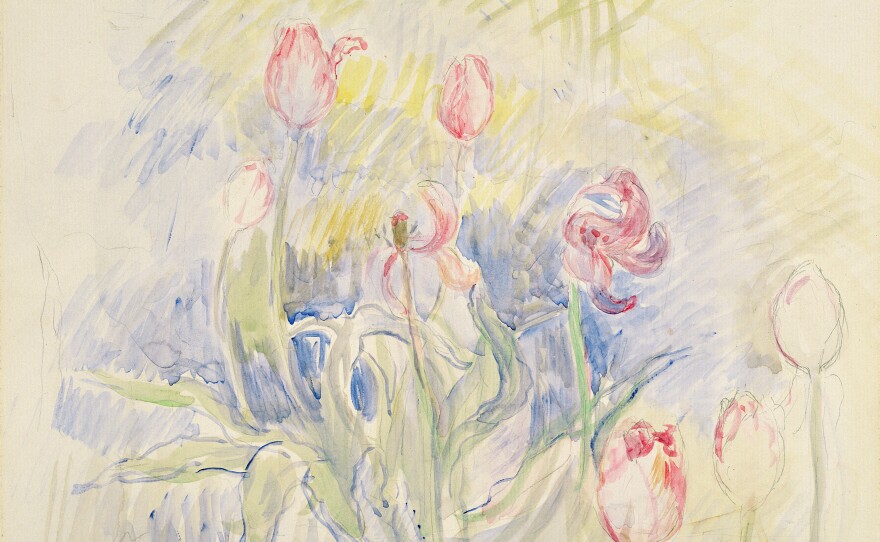

Linking the clothes to Impressionism, a dreary landscape by the young Monet hangs near a dowdy 1956 Dior. Tulips — a watercolor by Berthe Morisot — echoes a brighter Dior, from 1956.

The New Look that put Dior on the fashion map in 1947 — tiny waists, huge skirts, rounded shoulders — made a powerful statement, after all the deprivations of World War II. With his New Look, Dior was saying a new day had dawned.

"It was very important because it was a symbol of a return to prosperity — the beauty of life, you know," Muller says. It was the "return to luxurious things. ... It was like a fairy tale again."

"Dior and Impressionism" continues the fairy tale, with paintings and clothes, at the Dior Museum in Granville. The show ends Sunday.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))