Civic discourse is unraveling across the country, and one of the most pronounced local examples is at San Diego County Board of Supervisors meetings.

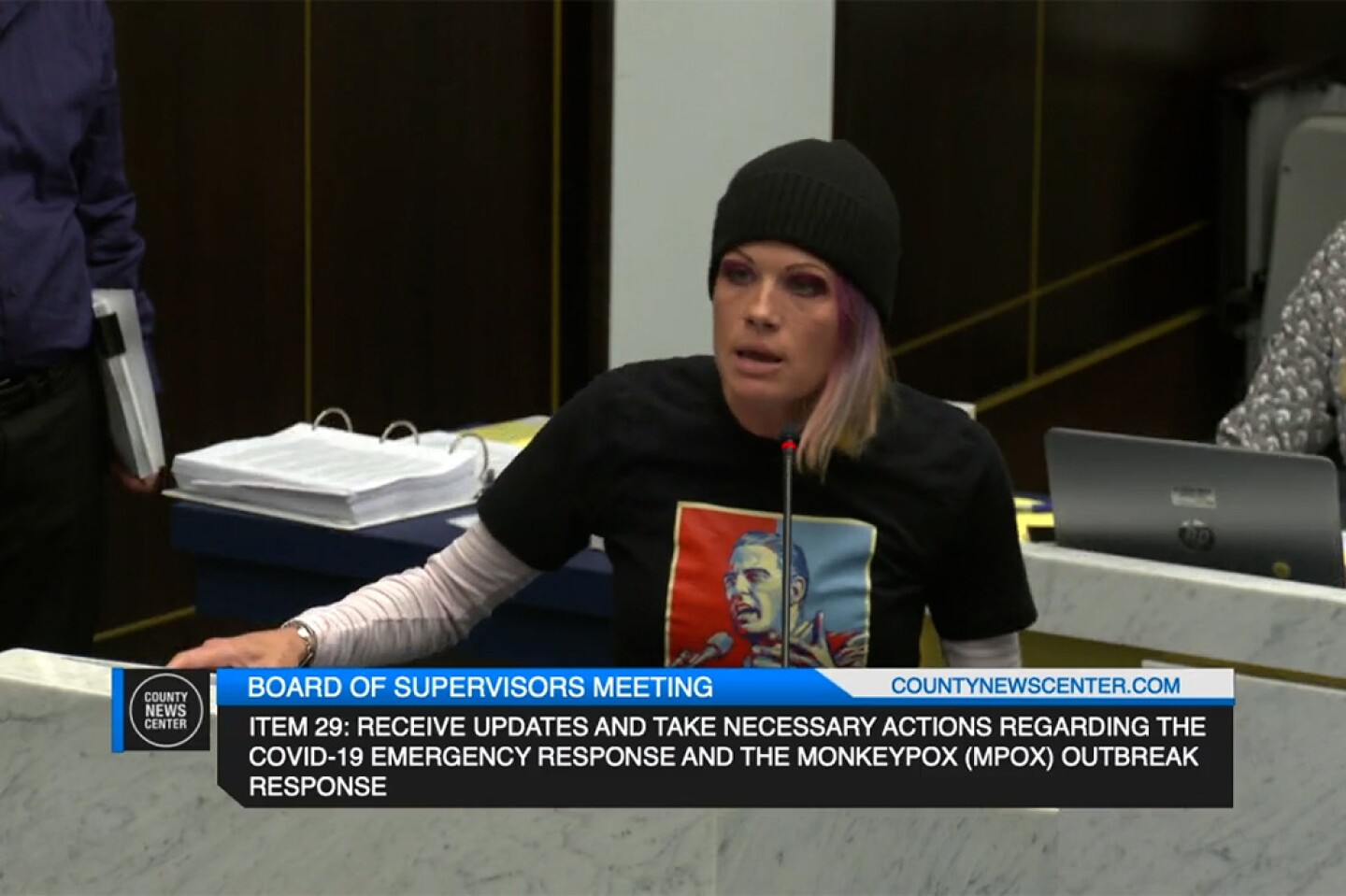

Name-calling, mockery, outbursts and profanity-filled tirades are now standard fare, sinking the mood and scuttling the people’s business.

A KPBS review of public comment at the meetings found incivility skyrocketed a year into the COVID–19 pandemic. In the fall of 2009, KPBS found two incidents. Last year, in the same three-month period, there were 167.

There was a time when people addressed the supervisors with politeness, even deference, using words like “honorable” to address them. Today, public commenters might open their remarks with, “Good morning, board of tyrants,” then accuse them of murder, wish aloud they would drop dead and lob racist insults.

The shift started in 2021 as supervisors became the face of COVID-related restrictions. Protestors flooded the meetings, public comment periods stretched on for hours, and the same group of commenters became meeting regulars. As their speech veered into threats or racist remarks, it raised questions of how to quell hostility that disrupted public meetings without violating First Amendment protections. That question continues today.

How did KPBS get this data?

KPBS created a sample method to analyze changes in civility at San Diego County Board of Supervisors meetings. We reviewed public comments over the same three-month period in 2009, 2014, and 2019 through 2023, which spanned the terms of presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. With input from academic researchers, a team of editors created a rubric of incivility categories: general incivility (disrespect, rudeness, sarcasm), profanity (swear words), intimidation (creating fear), meeting paused because of outburst, meeting ended because of outburst, indirect threats, sexual/offensive comments, accusations (calling someone racist or a “baby killer”) and direct threats.

Then, one KPBS reporter watched 54 meetings and noted when there were instances that met any of the category criteria. Next, a team of two reviewers did a blind control test of the original reviewer’s work, watching a random sample of clips that the original viewer highlighted, as well as a random sample of clips the original viewer did not highlight as uncivil. The reviewers agreed with the original reporter’s work more than 90% of the time, which outside experts said was satisfactory.

At one point, the comments even garnered national attention on late night talk shows. A man, who called himself Matt Baker, railed against supervisors over COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

“Your children and your children’s children will be subjugated!” Baker said, after delivering a lengthy whistle. “They will be asked, ‘How many vaccines have you had? Have you been a good little Nazi? Heil Fauci! Heil Fauci! Heil Fauci! Heil Fauci!’”

The man also brandished a copy of the Nuremberg Codes, alleging supervisors were transgressing the principles by conducting human experiments.

“The pandemic has left us with an unaddressed case of national PTSD,” said political scientist Carl Luna, who is director of the local Institute for Civil Civic Engagement in San Diego. “It scared the bejesus out of people. Frightened people will gravitate toward whatever conspiracies help them to make sense of the world. So you ended up with more people moving into crazy land.”

KPBS’s study

Luna’s analysis is backed up by KPBS’s own review of supervisors meetings. KPBS watched public comments from a three-month sample of meetings in 2009, 2014 and 2019 to 2023 — spanning the terms of presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Sure enough, the tide turned a year into the pandemic.

Keith Allred, executive director of the National Institute for Civil Discourse, which was created in the aftermath of the 2011 assassination attempt on former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, said the review tracks with his own network of research spanning the United States.

“Incivility and its sharper forms, political violence, are on the rise,” Allred said. “It is beyond question.”

Incivility examples

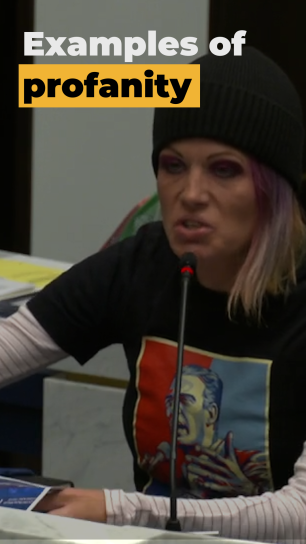

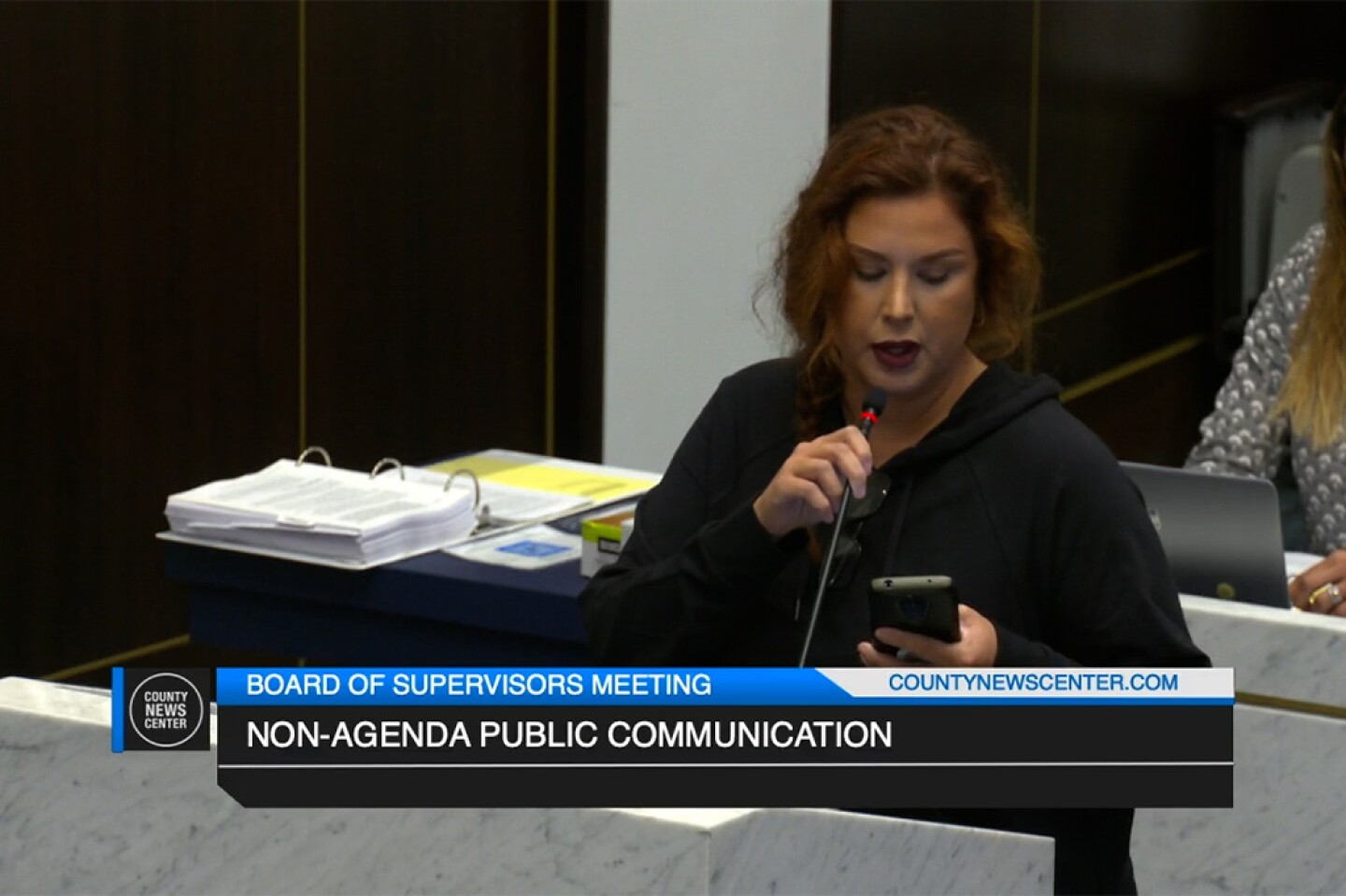

The surge in disrespect at supervisors meetings comes largely from the same group of people who turn out at every meeting. Some of frequent commenter Audra Morgan’s statements include:

“You could save people in the county and not murder them with shots.”

“What are you doing to stop human trafficking? Nothing because you are a part of it, maybe?”

“You’re felons. You should be taken to Gitmo.”

Some of the statements echo earlier periods of American history when racism was openly expressed. Comedian and frequent public commenter Jason Robo called then county Public Health Officer Dr. Wilma Wooten “Aunt Jemima” and later said the “blackest thing about her is her heart.”

Some speakers expressed ill wishes for supervisors. Robo once told Supervisor Nora Vargas he couldn’t wait for her “arteries to clog” and then said to Supervisor Nathan Fletcher, “Nathan, you should kill yourself.” It’s not unusual to hear the c-word and f-word during public comments.

“It's one thing to tweet things like that or write it in the comments, but to be in a room of human beings and to use some of the vilest language that we've seen is a statement of where we are in our incredibly divisive politics today,” said UC San Diego political science professor Thad Kousser.

Supervisor Terra Lawson-Remer said she regularly hears antisemitic rhetoric. She said commenters say supervisors should go to Auschwitz or be put on trial at Nuremberg.

“As a member of the Jewish community, my feelings are hurt,” Lawson-Remer said. “I feel afraid for people in our community.”

Former Supervisor Greg Cox, who left office in early 2021, said during his 26 years on the board he witnessed only a handful of outbursts from the public. He said the unpleasantness among the public began “building up” in 2020 during the early months of COVID-19 when people were forced to comment by phone because county chambers were closed.

“Once that happened, it became a lot more difficult to control the volume and level of excitement people were demonstrating in their comments,” Cox said. “We saw some phone calls that personally attacked our public health director. Totally inappropriate. Employees don’t deserve that.”

He said people going after supervisors is fair game within reason because they’re elected and “heat” comes with the position.

“If they want to call us a no-good SOB, that’s OK, but if they start using profanity willy-nilly and are excessive, get that person to calm down and escort them out of the chambers,” Cox said.

Roots of incivility

Lawson-Remer partly blames the nastiness at supervisors meetings on Trump and his disparaging comments about people of color and women dating back to his first run for president in 2016. She said that rhetoric normalized toxicity “that we’re all grappling with now.”

Luna said public discourse actually began to decline more than 15 years ago, with Obama’s election.

“While groundbreaking and historical, it also produced a backlash,” he said. “The fact that he was the first African-American president really discombobulated a lot of people who saw a different trajectory for America. You saw a rise in incivility then.”

Undergirding all of this is the waning of the American dream, illustrated by the high cost of housing, food and a college education. UCSD political scientist Kousser said COVID-19 vaccine mandates and forced business closures during the pandemic lockdown weakened faith in public institutions, and intensified the divide among Americans, all of which is amplified by social media.

“All of those things drive people's anger,” Kousser said. “They don't feel like they have anything in common with the other side.”

But even when national politics is divisive, local public government meetings have typically been the bedrock of democracy where hyperlocal issues are discussed, free of partisanship.

“One of the reasons that local debates and local politics survived polarization longer is that we had thicker and stronger connections to our neighbors, and we had a lot of trust that we built up, but that trust isn't free. It's being eroded,” said John Porten, a research manager who specializes in peace-building and local political development at the University of San Diego's Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice.

Porten said some of the erosion is being fueled by outside groups “whose reason for existence is to mobilize people” to attend public meetings and coach them on what to say to cause disruption.

San Diego psychologist David Peters believes the most susceptible people are the ones who are scared.

“People who feel threatened more often react with anger, and they react with unkindness and meanness because they feel more powerful then,” Peters said.

Commenters’ motivations

Frequent commenter Morgan blames her accusation-filled polemics on the supervisors themselves. She said it’s a reflection of “their actions” and the “negative” way they “act toward us.” The former actress also speaks at San Diego City Council and San Diego Association of Governments meetings.

“I come to share things with the people so that they can be more aware, so that I can wake up the masses so they can see what's really going on around them,” Morgan said.

Another regular is Consuelo Henken. She has accused supervisors of having an agenda to “subjugate” and “control people” and accused the board of “coming for their guns.” But she also said she considers them her “brothers and sisters” and “loves them.”

She said people think she is a Trump supporter, but she’s actually a registered Democrat. She said she’s worried about how inflation is affecting people’s ability to put food on the table and keep a roof over their heads.

She added she doesn’t mind the cuss words or insults thrown at supervisors.

“It's a shame that people are turned off by that,” Henken said. “But it's their opportunity to come in and, you know, voice what they feel.”

Incivility effects

Three years of relentless rudeness have plunged morale at supervisors meetings. The policymakers have had to call timeouts and pause meetings if public commenters continued yelling past their allotted time to speak.

The breaks to cool off not only disrupt and delay the public’s business, they endanger a sacred function of local government, said University of Connecticut sociology professor Ruth Braunstein. She calls public meetings “idealized spaces for representative democracy” because it's where the public gets to weigh in on decisions that affect them.

“If those meetings are being hijacked by loud negative voices, that's taking time and space from other citizens, and it's also derailing those conversations,” Braunstein said.

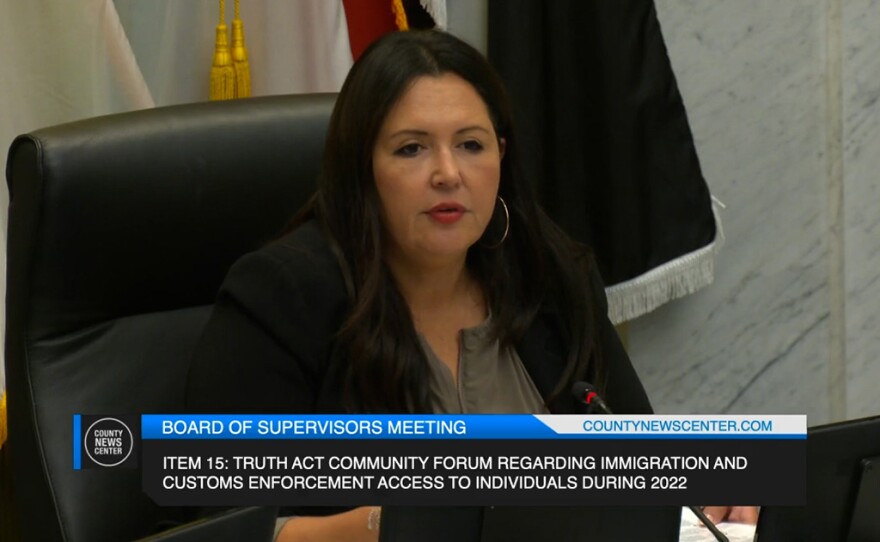

Exhibit A was a discussion late last year on the Transparent Review of Unjust Transfers and Holds, or TRUTH Act. Lawson-Remer said the goal was to have a public dialogue with immigrant communities about deportations.

But the talk was scuttled by regular public commenters Morgan and Henken who refused to stop talking. That meeting was paused until the next day. Public discussion of the TRUTH Act was not taken up again last year.

Erin Tsurumoto Grassi, associate director of Alliance SD, showed up to the TRUTH Act forum to comment but never got the chance because of the disruption.

“When you've taken the time to be able to do that, you're following the process, and then on top of that, it's not just that you're not being able to speak, you're having your dignity completely disrespected in the process,” Tsurumoto Grassi said.

She described a new reality at the meetings, where supervisors are not the only targets of contempt by audience members. She recalled being heckled herself when she and a colleague spoke against a resolution to shut down the border.

“They were yelling and screaming the entire time we were giving public comment,” she said. “It’s no longer about just showing up to oppose, but directed personal attacks as well. I would say an intention to just disrupt the entire process.”

Lawson-Remer said many constituents have told her they don’t want to attend meetings. They get drowned out.

“Being here and listening to this is just so upsetting and toxic,” she said.

But San Diego therapist Peters said the people who are repelled are the very ones who should be at the meetings.

“People of good intention and of good communication and self control pull back from spaces where there's ugliness because it feels unseemly,” he said.

The nastiness is also pushing elected officials to consider leaving their jobs. A USD study last year found more than half of office holders polled had thought about not running again because of harassment.

Allred, of the National Institute for Civil Discourse, said the public might be left with the most extreme voices to represent them.

Lawson-Remer said had she known how poisonous the supervisors meetings would become, she may have never run for office in 2020. But she doesn’t want to quit because she occupies a swing seat on the board.

She copes with the fallout from what she calls “the abuse and attacks” by surfing or going bike riding. But the next couple days after board meetings are “pretty terrible, frankly.”

Lawson-Remer gets little sympathy from Henken.

“If these people can't handle it, then get out of the arena,” Henken said.

But political scientist Luna said the sentiment of “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen,” doesn’t apply.

“When somebody has lit your kitchen on fire, it's not on you that you can't take the heat,” he said. “You've got to stop the civic arsonists out there from burning things down.”

First Amendment limits solutions

Despite the harassment, veiled threats and salty speech, supervisors have little recourse in confronting the incivility.

“For a threat to be unprotected by the First Amendment, it has to be that it is reckless in causing a person to reasonably fear for his or her physical safety,” said constitutional scholar Erwin Chermerinsky, who is also dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law. “Under the First Amendment, speech can't be stopped or punished just because it's offensive. Profanities are protected.”

UCSD political science professor Kousser said this reality leaves lawmakers in a tricky spot.

“How do you get the choir voices or the voices who can't be there to have a government serve their interests and make sure that it makes decisions without everything being drowned out by one voice,” he said.

Supervisors tried after Wooten was called Aunt Jemima. They restricted public comment time to one minute per person if more than 10 people wanted to speak. They also banned “threatening language, whistling, clapping, stamping of feet.”

And if sessions turn disorderly, Chairwoman Nora Vargas can pause the meeting after three warnings and have the unruly person removed. Vargas and the other supervisors declined interview requests. Lawson-Remer, who is the vice chairwoman, said those rules don’t go far enough.

“If I was running these meetings, this would be very different,“ she said.

Lawson-Remer said she would reduce the time someone can speak to one minute, unless the topic warranted more. And she would issue only one warning to disruptive speakers before ejecting them and prohibiting them from addressing the board in person again.

But that would be a violation, according to David Loy of the California First Amendment Coalition. A person can be removed for being out of control but cannot be barred from all future meetings based on that prior disruption. But he said supervisors can use the power of their own words.

“They can say, ‘We do not like this speech. We do not think it's acceptable. We have to allow people to say what they have to say because that is their First Amendment right. But we do not want this to impact other people's right to be heard,’“ Loy said.

Allred of the National Institute for Civil Discourse said adding perspective about the actual size of the group of rowdy people who regularly speak could help too.

“If I were a supervisor, I would keep putting that in context, I would say, ‘I am so grateful that so few of the 3 million people who live in San Diego conduct themselves that way,’” he said.

The rest of the onus in restoring civility at local government meetings may lie with many of those 3 million San Diegans and the country at large. Analysts said people must attend local government meetings no matter how odious they find them and make their voices heard.

But that’s just the start. Sociologist Braunstein said people have to return to neighborhood-based politics and organizations. That means transcending political, social and religious differences to solve problems in their own communities.

“You don't have to agree on everything,” she said. “You just have to work together on that. Then if a conflict emerges in your community, you have some of those social bonds, some of that trust built up so that it doesn't devolve as quickly into the pitched warfare that we're seeing today.”

No strategy would be complete, Braunstein added, without deradicalization. She said it’s up to everyone to help fellow citizens “identify misinformation and disinformation,” debunk conspiracy theories and immunize them from future manipulation.

“There are organizations right now that are working with communities to equip people with tools to build up the resiliency and deal with some of these threats, particularly young people who are growing up online and are exposed to all kinds of disinformation and misinformation,” Braunstein said.

Political scientist Luna said inaction isn’t an option. Democracy is like a relationship. It demands conversation and compromise to tackle basic problems and move forward. Without it, people lose faith in government institutions.

“And those who want to just burn it all down will get a better opportunity to do so,” Luna said.