Seventy-five years ago, before Theodor Geisel rocked the culinary world with green eggs and ham or put a red-and-white striped top hat on a talking cat, Geisel (whom you probably know better as Dr. Seuss) was stuck on a boat, returning from a trip to Europe.

For eight days, he listened to the ship's engine chug away. The sound got stuck in his head, and he started writing to the rhythm. Eventually, those rhythmic lines in his head turned into his first children's book: It was called And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

The story, which turns 75 this year, is about a boy named Marco who wants to tell his father an interesting story about what he saw that day on his walk home from school — but the only thing Marco has seen (other than his own feet) is a boring old horse and wagon on Mulberry Street.

Marco laments:

That's nothing to tell of,

That won't do of course ...

Just a broke-down wagon

That's drawn by a horse.

That can't be my story. That's only a start.

I'll say that a ZEBRA was pulling that cart!

And that is a story that no one can beat,

When I say that I saw it on Mulberry Street.

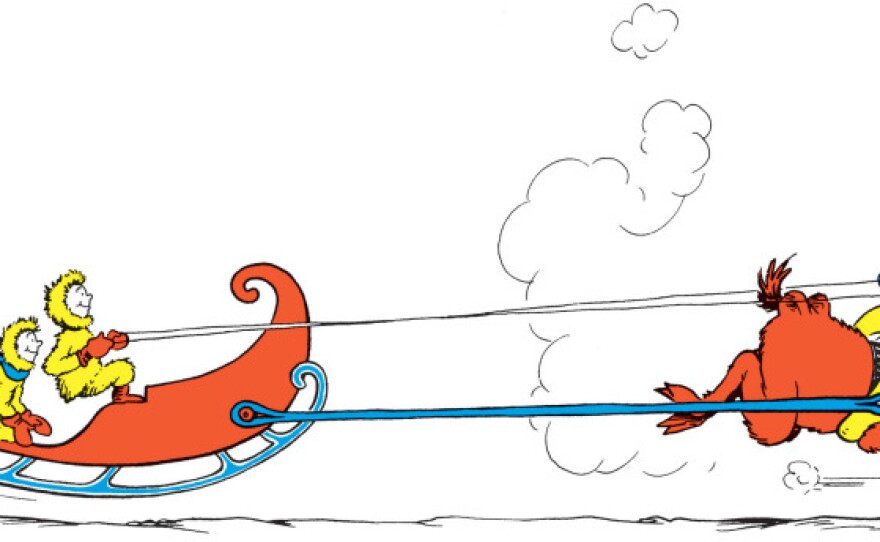

Soon Marco's imagination is running wild — the zebra morphs into a reindeer, and the wagon becomes a golden chariot and then a fancy sleigh.

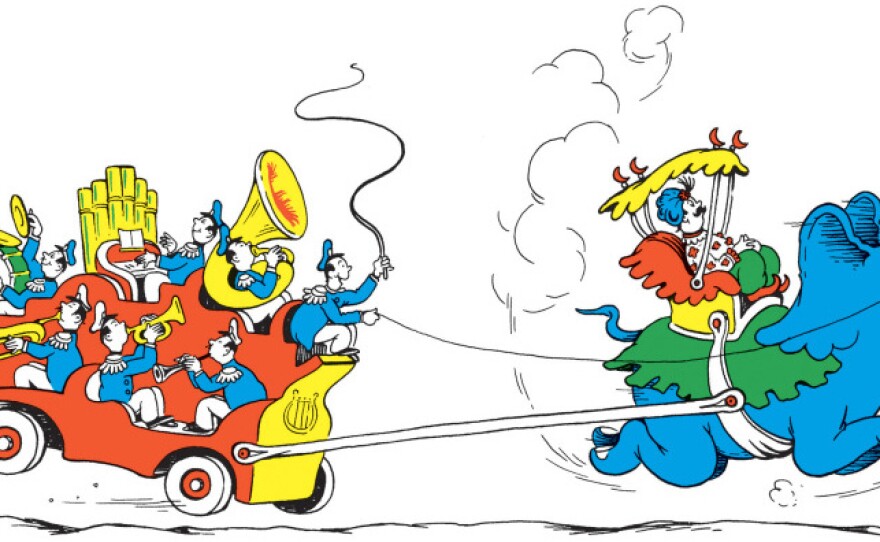

But why have a simple sleigh pulled by a reindeer, when the sleigh could be a brass band, and the reindeer could be an elephant? The little boy imagines the elephant he'll describe to his father:

I'll pick one with plenty of power and size,

A blue one with plenty of fun in his eyes.

And then just to give him a little more tone,

Have a Rajah, with rubies, perched high on a throne.

On and on it goes; two giraffes help the elephant pull the brass band, as a squadron of policemen on motorcycles escort the parade past the mayor and the alderman as an airplane showers confetti from above.

In the end, Marco knows his father won't tolerate a made-up story, so when Dad asks about the sights Marco saw on the way home from school, the dejected little boy just tells the boring truth:

"Nothing," I said, growing red as a beet

"But a plain horse and wagon on Mulberry Street."

Dr. Seuss didn't have an easy time selling the bittersweet story to publishers. "It was rejected 27 times," says Guy McLain, who works at the Springfield Museum in Geisel's Massachusetts hometown.

McLain has become a local expert on Dr. Seuss. He says Mulberry Street might have never been published — if it hadn't been for a chance encounter Geisel had one day as he was walking home in New York City.

"He bumped into a friend ... who had just become an editor at a publishing house in the children's section," McLain explains. Geisel told the friend that he'd simply given up and planned to destroy the book, but the editor asked to take a look.

He said if he had been walking down the other side of the street, he probably would never have become a children's author.

It was a moment that changed Geisel's life.

"He said if he had been walking down the other side of the street, he probably would never have become a children's author," McLain says.

The book was published in 1937. It got great reviews, and the rest is history.

But why Mulberry Street? Turns out, it's a real-life street in Geisel's hometown.

"It was a street very close to his grandparents' bakery," McLain says. "And I think also ... it was the rhythm, the sound of the word that was very important with Dr. Seuss. Because there's nothing special about the street, really."

Except for the fact that the ordinary little street launched one extraordinary career.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))