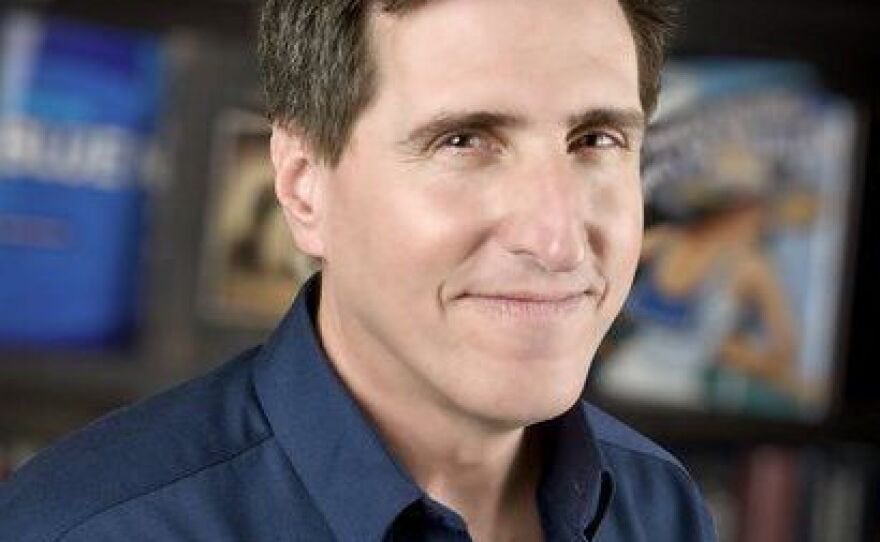

Paul Rudnick has made a name as a playwright, novelist, columnist and screenwriter. Now he's turned his attention to the Young Adult market with a kind of Cinderella story starring a young woman named Becky, who's grown up in a trailer park.

When Becky's mom dies, she discovers a mysterious phone number. Calling it, she receives a mystical offer: A legendary New York fashion designer will make her three dresses, one each in black, white and red, and if she'll only wear them — and do everything he says — she'll become history's most beautiful woman.

The book's voices are diverse, funny and surprising. Rudnick joined NPR's Rachel Martin to talk about the power of fashion, the terrors of first seeing someone reading your work, and the high that comes from hearing an audience laugh.

Interview Highlights

On capturing the voices of teenagers

"[It was] shockingly easy. Shamefully easy, I would even say. When I first had the idea ... I tried a lot of different approaches. I even wondered, was this a play, or a movie or a book? And it wasn't until I began writing in the voice of Becky herself — in the voice of an 18-year-old girl — that the story really flew. So I'm not quite sure what it says about me, or what a mental health professional might conclude, but I had a blast."

On his favorite magical device in the story

"I guess because I've been enough of a fashion addict, and I've read enough issues of Vogue in my life, that I love the idea of endowing clothing, or high fashion, with the power that we almost wish it had. I think whenever anyone is getting dressed for the evening, especially if it's a Friday night or if it's an occasion or if it's a first date, you're hoping that what you look like will elevate you. Your outfit and your shoes and your makeup and your hair will send the absolute perfect message to whoever you're about to meet — even if you don't know who that is.

"So I love taking that final step, of saying, 'OK, you're gonna put on this dress, and it's gonna do everything you could ever hope for and beyond.' "

On whether that magic ever happens in real life

"It can work until you leave the house. [Laughs.] Or, what's shocking to me, is every once in a while, you see a photo — whether it's something online, on someone's phone, on someone's Facebook page — and you weren't aware that that photo was being taken, and you look OK! Or even better than that!

"And depending on what kind of mood you're in, you can say, 'Oh, you know, it was a trick of the lighting. It was because I was standing in just the right corner.' Or you could say, 'Oh my god, I guess for at least a split second, I looked like that!' I think that could kinda make your day."

On the pleasures of writing screwball comedy

"I think I come from a pretty funny family, where humor was always sort of a very important balance wheel, especially when things went bad. Sometimes a joke was the only weapon you had. In fact an early play I wrote, called Jeffrey — people didn't imagine that this play would be possible, 'cause it was a comedy set during the AIDS crisis. But again, I saw people all around me who had such great senses of humor. And humor was the only thing that could get anyone through a situation like that, often — you know, until medicine helped a little bit.

"And beyond that — it's funny, I never sit down and say, 'This is going to be comic; this will be a screwball romp.' That's kind of what happens. That's just the way my brain is wired, which I'm eternally grateful for. And I guess I also love the challenge of providing that particular breed of pleasure."

On seeing people respond to his work

"When they actually laugh — first, I'm incredibly grateful to the actors involved. But beyond that, it's an enormous gut satisfaction that I somehow can't imagine a writer gets from a serious work. (Although it's also deeply and selfishly satisfying to make a reader cry.) But when you say, 'Yeah, that joke worked,' or 'That character was funny,' or 'That hit a comic nerve,' it's a real high."

On first seeing someone reading one of his books

"I wanted to fall to my knees; I wanted to write them a check. I wanted to photograph them. I wanted that photograph to be turned into a stamp. I just couldn't believe it. I immediately assumed that a member of my family or a friend had paid them to do that. ... Or that if I looked too closely, they'd actually have hidden another book inside the cover of mine.

"There was some sort of insane high that I got, because I thought, 'Oh my God, someone is actually reading the book; they seem fairly far along in it, so they're gonna finish it. They seem to be enjoying it. And My God they paid for it.' I think it's every writer's secret fantasy."

On why he didn't introduce himself to that reader

"I let it be a private moment out of sheer paranoia. You know, because I didn't want to say, 'Oh, you know you're reading my book,' and have them say, 'Eh. Yeah, somebody gave it to me; I don't get it.' I thought it was safer, to let it — to keep the bubble aloft."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))