The home of Sean Morey bears the impressive signposts of his 10-year career in the NFL: a Vince Lombardi trophy for his Super Bowl championship with the Pittsburgh Steelers in 2006. A hefty Super Bowl ring. A framed photograph showing Morey in midair, launching himself like a missile to block a punt. With that play in 2008, his Arizona Cardinals became the only team in NFL history to win a game in overtime with a blocked punt.

But look in Morey's medicine cabinet, and you'll find other vestiges of his NFL career: the bottles of pills that he takes to mitigate the effects of brain injury he sustained playing football. Propranolol to help with debilitating headaches. Lexapro, an anti-depressant, to -- as Morey puts it -- "lengthen my fuse." Ritalin to help him focus. Trazodone to help him sleep.

Morey suffers from post-concussion syndrome.

Hundreds of other NFL players have been diagnosed with far more serious conditions: dementia, ALS, Parkinson's and severe cognitive decline. On autopsy, the brains of more than 50 players show clear signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a progressive degenerative disease.

Morey hopes that by retiring from the NFL when he did, in 2010, he's avoided that fate.

By the end of his career, Morey was considered one of the best special teams players in the league. Special teams players sprint down the field to block and tackle on kickoffs and punts. Because of the speed and the explosive collisions that result, the kickoff return has been considered one of the most dangerous plays in football.

Morey was small for the NFL -- just 5 feet 10 inches and 190 pounds. But he was fast and relentless. He was what's called a wedge breaker. "I basically hit and blocked everything I could, as hard as I could," he tells me. "Anything that moved."

And over his career, he suffered dozens of concussions. "Somewhere in the high 20s. You know, I was pretty reluctant to admit how many I'd had," he says.

But he does remember them in photographic detail; for example, one concussion that knocked him unconscious in 2007. "I was asleep," he recalls. "You feel like you're waking up from a dream. But you see the grass, you hear the noise, and you realize, 'Oh! I'm in a football game!' So you get up, and I start walking, but I'm walking sideways."

Another time, he stumbled off the field to the opposing team's bench.

In his final season in 2009, he had four concussions in just one game, he says. "Every time I hit somebody it was like getting tasered," he says.

That was when doctors told him it was time to hang up his helmet. "They said, 'There's a chance you'll never get over these headaches,' " Morey says. " 'You've been symptomatic for too long, and I just can't with a clear conscience let you play football anymore. You've gotta retire.' "

When I sat down to talk with Morey and his wife, Cara, at the home they share with their three young daughters in Princeton, N.J., they told me about the symptoms that Sean has shown over the past four years. He'll get crushing migraine headaches that knock him out of commission for days at a time. He'll launch into bouts of explosive rage, shouting at his family. He has trouble focusing, forgets things and loses his train of thought.

Sean says there's no question these symptoms are related to brain trauma sustained playing football. "You cannot have that kind of pain and have it not be related to brain damage," he says. "The dysfunction, the pain, the misery, the confusion, the desperation, the depression. ... There were instances in my life that would never have existed had I not damaged my brain."

Cara Morey has watched her husband turn into someone she doesn't recognize. "He gets a look in his eyes that you're pretty sure you've never met this person before. ... It's very scary. It's a type of rage that I had never seen, and I don't think anyone should ever see, and I don't think my girls should ever have seen it."

"There's years of my life, but more importantly, there's years of my daughters' life, that I wish I could rescript," says Sean.

Cara admits that she may be in denial about the extent of her husband's injuries and whether he might get progressively worse. "I don't want to ask myself that question because I'm scared of what the answer would be," she says.

Morey is among dozens of retired NFL players who have agreed to donate their brains for medical research when they die. He hopes his brain might provide some answers.

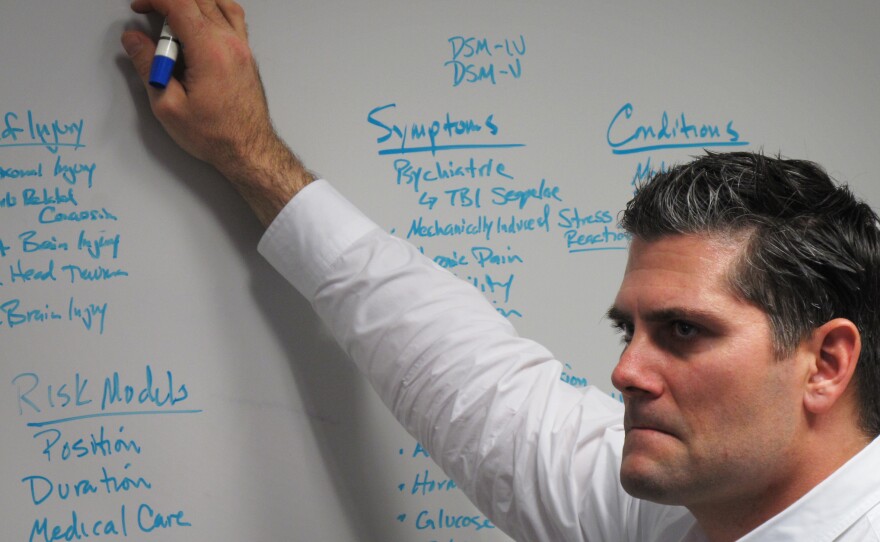

For now, he accepts that the damage he sustained is permanent. He doesn't think it's getting worse, so he tries to adapt. He writes a lot of reminder notes, sets alerts on his phone, stays on top of his meds. And he has devoted himself obsessively to learning about concussions and helping other players who are suffering.

He was founder of the NFL Players Association's committee on traumatic brain injury. Now, he's an independent advocate for players' health.

Morey is constantly on the phone with other retired NFL players, trying to persuade them to join him in intervening in the $765 million concussion settlement that's now being reviewed by U.S. District Judge Anita Brody.

The deal was reached between the NFL and thousands of retired players. But Morey is concerned that a lot of players are left out: players who may not have the most serious conditions, such as Parkinson's or ALS, but who are still suffering the consequences of brain injury in the NFL.

This Sunday, Sean Morey will tune in to watch the Super Bowl from home. He's hoping for a tough, physical, exciting game. But he'll be watching with a very critical eye. "Every time someone gets concussed, I'll rewind it," he tells me. "I'm looking at, did they even evaluate him? Did anybody look at him? Did they shrug it off? What's the report back? Well, they're saying, 'Oh, he got shaken up on the field.' They won't use the word 'concussion.' I'm like an educated, informed spectator. I'll watch it more closely."

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.