The Affordable Care Act requires all Americans to get health insurance or pay a penalty. To help coax people to buy a health plan, the federal government now subsidizes premiums for millions of Americans.

In just a couple of months, the Supreme Court will rule in a major case concerning those subsidies. The question to be decided is whether the law authorized that financial help nationwide, or just in the minority of states that set up their own insurance exchanges. A decision to take away those subsidies could leave millions without insurance.

Attorney Tom Goldstein, who runs SCOTUSblog, has closely followed the case and says the law is ambiguous. "This is a real, serious question," he says. "The law doesn't tell you whether Congress wanted to limit the subsidies only to those states where the state itself went to the trouble of setting up the exchange, or whether Congress wanted everybody who needed the help to be able to get the subsidies."

In my home state of Louisiana, a lot of people could be affected by the upcoming court decision. About 186,000 people there have used HealthCare.gov to buy insurance, and nearly 90 percent of them get subsidies. Here are the stories of a few of the people I spoke with:

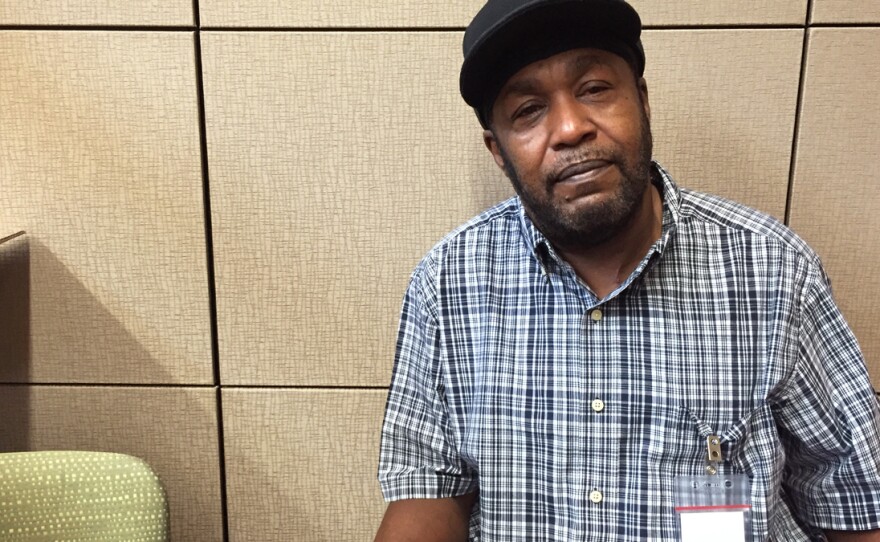

Carlton Scott

Carlton Scott is 63. Sitting at the kitchen table of his home in Prairieville, La., near Baton Rouge, Scott tells me he worked at a chemical plant for 30 years before he retired. Last fall his company let him know it was scaling back his retiree benefits.

"Around October, he says, "they wrote me a letter saying [that] in December we'll no longer be covered."

Those reduced benefits included Scott's health insurance, which he was really counting on.

"I thought they would take me to my grave," he says. "I really thought the company would take me to my grave."

He was deeply angry, and in a bind. At 63, Scott is too young for Medicare, and Louisiana hasn't expanded Medicaid. Obamacare, he says, was a good option for him.

He pays $266.99 per month, "to the penny" for his plan from BlueCross BlueShield of Louisiana. Like a lot of people I spoke with, Scott could rattle off the exact amount. Money is tight and people track their expenses carefully.

If Scott loses his subsidy, he may eventually lose his health insurance, too. He could pay more for a little while if he has to, he says. He gets $2,600 a month between Social Security and his pension. But he worries about friends who don't make as much.

"I got a friend of mine ... down the street," Scott says. "He gets Social Security and pension too. But it's not as much as mine — not half as much."

When asked about the case soon to be decided by the justices of the Supreme Court, Scott laughs.

"They all got insurance, too," he says. "I guarantee you that. They all got insurance."

He thinks the court should "leave it like it is. I mean, what are people going to do? Get sick, go to the hospital [and say], 'I don't have insurance. Won't you please help me anyway?' " It just won't happen, he says.

LaTasha Perry

LaTasha Perry is at the other end of her career. She's 31 and works at the front desk of a community health center in Plaquemine, La. She's healthy and rarely needs a doctor, she says, but bought coverage under Obamacare because it was cheaper than paying the penalty.

Perry's children have Medicaid as their health coverage. Her job offers health insurance, but she doesn't buy it. Like a lot of people who work but don't make a lot of money, she says she can't afford the insurance her company offers.

"I would pay at least $100 a month for the insurance here," Perry says. "With my subsidy, I pay $13."

That leaves her money for other necessities, she says. "Food for my kids. I'm a single parent. It's hard." Charles Dalton

Charles Dalton, of Shreveport, was very glad to get Obamacare coverage. He's 64, and after retiring as a paramedic didn't have any health insurance. Then he got sick.

"I'm disabled," Dalton says. "But I would be totally incapacitated without seeing this doctor."

Before the Affordable Care Act became law, insurance companies could take a person's health status into account when setting the price of the monthly premium, and even refuse an applicant for health reasons. That used to make insurance unavailable or unaffordable for many sick people. And now — with subsidies — Dalton says he pays $149 a month. He hopes the Supreme Court doesn't touch the subsidies.

"They're just going to make a difficult situation more difficult," Dalton says. The Affordable Care Act, he says, has helped make his existence "more livable."

"You're not asking for a handout," Dalton says. "But if you get a helping hand, the last thing you need is for it to be snatched out from under you."

Attorney Tom Goldstein says the Supreme Court justices have a particularly tough job, trying to balance the specifics of the law with its human dimensions.

"The consequences are so real and so powerful," Goldstein says, "that, if the challengers win here — and maybe they deserve to win, maybe it's what Congress intended — but it's hard to avoid the conclusion that millions of people would lose access to health insurance."

This story is part of NPR's reporting partnership with WNPR and Kaiser Health News.

Copyright 2015 Connecticut Public Radio. To see more, visit http://www.wnpr.org.