In 1849 an American farmer watched a sow give birth and was moved to record a diary entry: "Pigs! Pigs! Pork! Pork! Pork!"

The writer's enthusiasm — dug up by historical geographer Sam Bowers Hilliard for Hog Meat and Hoecake, his examination of Southern foodways — is understandable. Swine reproduce far more quickly than cows and sheep, thanks to brief gestation periods and large litters, and pork only improves when cured with salt and smoke. If your goal is to produce a great deal of meat and then store it at room temperature — crucial before refrigerators came along — the pig is the animal for you.

Enormously useful as they are, swine have not been universally adored. The history of pigs is a tale of love and loathing. As long as pigs have existed, people have weighed their hunger for meat against worries about how the animals lived and what they ate. And today, we have just as much reason to worry about how pigs are living.

Pigs and people have similar digestive systems and similar diets: Both are omnivores who thrive on meat, roots and seeds. It was food that first brought them together. About 10,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers in Anatolia — now Turkey — settled down into villages. Almost immediately, Eurasian wild boars began slinking into town to devour scraps, spoiled grain and rotten fruit. In time, some of those scavenging boars evolved into domestic pigs. Sus scrofa domesticus was the new species perfectly adapted to living alongside people.

By 1,000 BC, however, our partnership with pigs had soured, a development marked most notably in the Book of Leviticus, which deemed pigs "unclean." The Israelites could eat any beast that "parteth the hoof, and is clovenfooted, and cheweth the cud." Cows, sheep and goats got the nod; pigs did not: "though he divide the hoof, and be clovenfooted, yet he cheweth not the cud."

The Koran followed suit in the seventh century AD: "forbidden to you is ... the flesh of swine." Today a quarter of the world's population — 14 million Jews and 1.6 billion Muslims — must avoid pork.

The rules strike many as arbitrary, and there has been no shortage of attempts to expose the supposedly hidden truth. The mostly popular explanation — that the ban protected against trichinosis — is almost certainly untrue (there's no evidence the parasite existed in ancient Palestine, and other meats could be equally dangerous). Some scholars point to the unsuitability of pigs for desert conditions, or the fact that pigs and humans might compete for food. Others suggest that poor people could raise pigs at home and thereby gain control of their own food supply; rulers, intent on total control, banned pigs so the poor would be hungry unless fed by the state.

All of these theories hold a piece of the truth, but the best explanation lies in Leviticus. The approved animals "chew the cud," which is another way of saying they are ruminants that eat grass. Pigs "cheweth not the cud" because they possess simple guts, unable to digest cellulose. They eat calorie-dense foods, not only nuts and grains but also less salubrious items such as carrion, human corpses and feces. Pigs were unclean because they ate filth.

The Jews were not alone in this prejudice. In the great civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, priests and rulers avoided pork at all costs.

Just across the Mediterranean, however, the Romans loved swine with a passion matched by few people before or since. Romans sacrificed pigs to their gods and created an elaborate pork-based cuisine, including some dishes—such as roast udder of lactating sow—that could make even a gentile shudder.

What accounts for these differing views? In the Near East, an arid land, most pigs lived as urban scavengers. The Italian Peninsula, by contrast, boasted vast oak forests, and Rome imported wheat by the shipload. Rather than eating garbage in the streets, Roman pigs spent their days dining on acorns and grain.

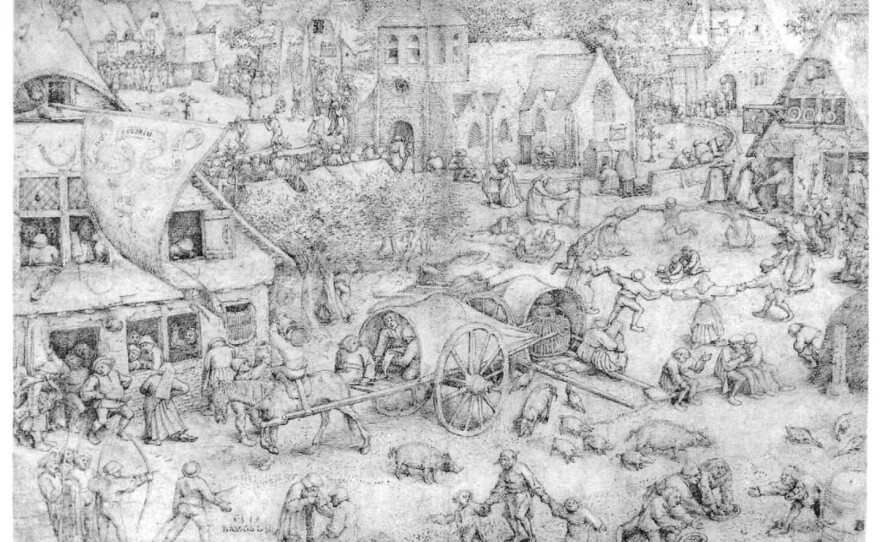

The reputation of pork depends upon the life of the pig. In early medieval Europe, when most pigs foraged in the woods, pork was the preferred meat of the nobility. By 1300 most forests had been felled, and pigs became scavengers. In a medieval British text, a woman explains that she won't serve pork because pigs "eat human shit in the streets." Pigs also dined on human flesh, which was available because executed prisoners, among others, were left unburied. In Shakespeare's Richard III, the title character is described as a "foul swine" who "Swills your warm blood like wash, and makes his trough / In your embowell'd bosoms." An Irish religious text noted, "Cows feed only on grass and the leaves of trees, but swine eat things clean and unclean."

Pigs today eat a wholesome diet of corn and soybeans, but people have new reasons to avoid pork.

The most intelligent of farm animals, swine raised in the confined feeding operations that now dominate the industry endure the most inhumane conditions. They stand on slatted concrete floors, trampling their waste into gutters below. Most sows still spend nearly their entire lives confined to "gestation crates," metal cages so tiny the animals can't turn around (though this is changing.) Sick piglets are killed by being grabbed by their hind legs and slammed against the floor, a practice known as "thumping."

Critiques of such practices, once the concern mostly of animals rights groups, have gone mainstream. This year the restaurant chain Chipotle kept carnitas off the menu at some locations because it couldn't find enough pork raised according to its stricter welfare standards. Other chains, including McDonald's, still serve conventional pork but have pressured pork suppliers to change their ways. As a result the largest pork producers have vowed to phase out gestation crates.

Smaller producers have taken larger steps, adopting methods that would look familiar to ancient Romans: Their pigs roam on pasture or gobble acorns in the woods. That's the kind of agriculture that might prompt not disgust but enthusiastic cries of, "Pork! Pork! Pork!"

Mark Essig is the author, most recently, of Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig. He holds a Ph.D. in history from Cornell University and lives in Asheville, N.C.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.