With his ambulance sirens blaring, Edmund Hassan is speeding to a home in South Boston, after getting a call that someone there is unconscious. He's deputy superintendent of Boston Emergency Medical Services, and he suspects an opioid overdose. These days, he says, his workers have to administer Narcan, the drug that reverses that kind of overdose, roughly three times in every eight-hour shift.

With overdoses from heroin and opioid painkillers a leading cause of accidental deaths in the U.S., people on the front lines of the opioid battle are increasingly turning to Narcan (also known as naloxone) to save lives. In many cities, police, school nurses, and family and friends of drug users, as well as drug users themselves, all commonly carry Narcan now. The Centers For Disease Control and prevention reports that the use of naloxone kits by lay people reversed at least 26,463 overdoses between 1996 and June 2014.

But being saved in the short run from an overdose is no guarantee that someone will stop using drugs. Narcan is one tool to improve the odds of survival, many health providers say, but more long-term solutions to addiction are needed, as well.

Hassan's radio crackles in Boston, and his hunch about the case he's about to face is confirmed: an overdose. Additional workers are dispatched to the scene.

When Hassan arrives at the single-family home, a team of emergency workers and firefighters is already there. Several people are running to the back of the house and down some steps into the basement. In the far corner, a middle-aged man is on the ground; two people are sobbing nearby. The crew rushes to administer naloxone, squirting it into the man's nose.

"OK, he's getting some Narcan now," Hassan explains to a woman standing nearby.

"You just found him here?" he asks her.

"Yes," she says, arms clenched around her body, tears in her eyes. "He's my husband."

"Has he ever used heroin before?" Hassan asks her.

"A long time ago," the man's wife says. "I thought he stopped." His son had discovered him unconscious in the basement.

We are not identifying the man because of medical privacy concerns. Hassan tries to reassure the family, as he and his team continue to work.

The emergency workers massage the man's chest, clap their hands in front of his face, yell his name and adjust a plastic ventilator over his mouth and nose to try to get him breathing again. Hassan explains that an overdose slowly shuts down a patient's respiratory system so the man needs help breathing until the Narcan kicks in.

After more than five minutes, the man's eyes open, and he groans.

"Come on, you want to try to get up?" a member of the team asks, as they walk him to the ambulance. Hassan says the emergency room will take over from here.

"As EMS providers, this call is a success," Hassan says. "In the big picture of health care, is it a success? Well, no, it's incomplete right now. For it to be a total success he'd get into a rehab program and never do heroin again."

After A Narcan Revival, Most Don't Get More Treatment

But, that's not what usually happens Hassan says. "At some point, we probably took care of him before."

Another 31-year-old Boston man named Joseph, who didn't want his last name used because of the stigma associated with his past substance abuse, had just the sort of experience Hassan is talking about.

Joseph says he's been revived by Narcan "about 4 to 5 times in my life" — and it was a terrible experience each time.

"It's horrible," he says of the experience of waking up after getting Narcan. "The worst withdrawals you ever felt in your life. You feel like you want your high back, almost. You just wanna die, you know. It's that bad."

The problem, he says, is that the lure of heroin's high can be so great that the risk of facing Narcan's nasty side effects — even the risk of dying from an overdose — aren't strong enough to beat back the addiction.

Joseph says that most of the time he's been brought to an ER because an overdose, he's been discharged after only about three hours, without any recommendations about getting further treatment.

"They let you kinda sleep it off," he says. "They just discharge you and they tell you you need to get help — you need to do something."

Many ER doctors say that after a Narcan revival, if a patient appears to be breathing fine and walking, they are indeed discharged within a few hours. Many are so sick and uncomfortable they just want to leave. And even if they do want further counseling and extended treatment for their addiciton, access is limited by availability and insurance.

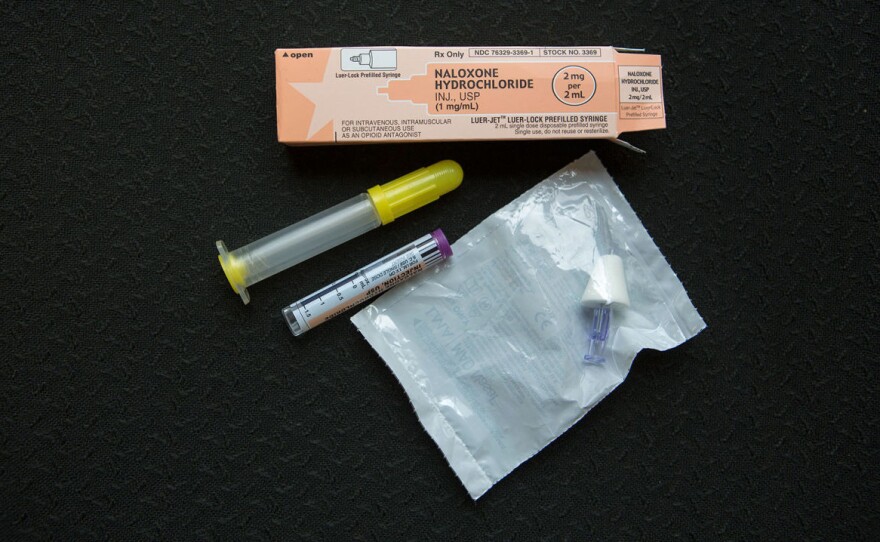

"For myself, basically, they'd have to be able to walk safely, be able to have a conversation, be able to take fluids before they're released," says Dr. Edward Bernstein, a professor at Boston University, and an emergency physician at Boston Medical Center. Before the patients leave after a Narcan revival, most are given their own Narcan kit and information about further treatment.

But less than half the overdose patients revived with Narcan at the medical center actually do go on to get follow-up help with their addiction. That's often because there are no beds available, he says.

"You do feel helpless," Bernstein says. "Especially since we're trying our best, and we have all these different tools now."

About A Third Of Patients Revived By Narcan More Than Once

Repeatedly having to use Narcan on the same patient, can also make a health provider feel helpless, Bernstein says. About 30 percent of those revived with Narcan at Boston Medical Center have been revived there more than once, he says, and about 10 percent of patients more than three times. Those statistics are in line with what's seen in ERs elsewhere, public health officials say.

But that doesn't mean Narcan isn't working, Bernstein says. He believes the repeated revival rate often seen in ERs reflects the fact that addiction, though still too often stigmatized as a failure in character, is a chronic health problem. And like asthma, hypertension, heart failure and other chronic health problems, it's hard to control, and requires multi-faceted treatment.

"Asthma, hypertension, heart failure — we see these folks back numerous times," he says. "So I'm not surprised people with opiate addiction and other addictions come back to the emergency room more than one time."

The broad distribution of Narcan kits is a useful part of the solution, he says — though just one part. "We have to work on, basically, one day at a time, one step at a time, one life at a time. I think it would've been a lot worse if we hadn't had all these things in place."

Sometimes, after a Narcan treatment, Joseph says he felt so bad he just went home and shot up more heroin. "It's a vicious, vicious cycle," he says.

But a cycle he's hoping to break. After struggling with opioid use for 15 years, he's been in treatment for more than a year. Narcan, he says, has been just one step on his journey to recovery.

Ed Hassan says the bottom line is that Narcan saves lives so Joseph and others addicted to opioids can one day save themselves.

"Our job, as EMTs and paramedics, is dealing with the immediate crisis," Hassan says the day he revives the man in a South Boston basement. "We got him breathing again. That's a victory for us, but it is a very small victory. I guess it's one small battle in a very big war."

Hassan may never know if the man in South Boston will win his battle. Though the emergency crew did give him a referral for further addiction treatment, we were prevented by medical privacy laws from learning if he ever followed up and got it.

We left him at the doors of the ER, where his son walked up to the stretcher, took his father's hand and said, "I'm glad you're alive, Dad."

A longer version of this story ran on WBUR's blog CommonHealth, where you can find more coverage of the opioid addiction crisis in Massachusetts.

Copyright 2015 WBUR. To see more, visit http://www.wbur.org.