When I was 17, my mother sent me to live with some relatives in South America for a year. I'd been screwing up royally and my antics were becoming difficult for her to manage as a struggling single mother of three. She'd been threatening for a long time to ship me off to Colombia. I never imagined it would happen. But she'd finally had enough, and after many tears and reservations, she followed through on those threats in hopes that I'd return grateful and rehabilitated. She didn't know her plan would work as well as it did, or that over the course of the next 12 months I'd learn to love something other than marijuana, rap music, and vandalizing private property with a spray can. That something was literature, and in particular, Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis.

Published in 1915, 100 years ago this month, The Metamorphosis remains the standard by which I measure any supposed work of genius. It was also one of the first things my uncle gave me when I'd arrived in Bogotá as a punkass teenager. "Take this," he told me. "This will help to pass the time." It did, and I was floored by the magic of it. After that, I read everything of Kafka's I could get my hands on. But it all began with The Metamorphosis, which served as something of a gateway for my rehabilitation.

The Metamorphosis opens with the most famous — and possibly most evocative — first sentence in all of literature: "When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin." This vermin into which Gregor gets transformed is a sort of cockroach or beetle with wings; Kafka never gives us specifics, nor does he offer the reader any clear explanation as to how or why it happened. But that sentence sets the scene for Kafka's exploration of alienation, existentialism, and what it means to belong.

"I cannot make you understand," says Samsa regarding his transformation. "I cannot make anyone understand what is happening inside me. I cannot even explain it to myself." For me, a lost teenager adrift in a new country, these words provided a kind of comfort. They made me realize that no one has it all together, and that if I chose to, I could find some solace and perhaps even strength in that fact.

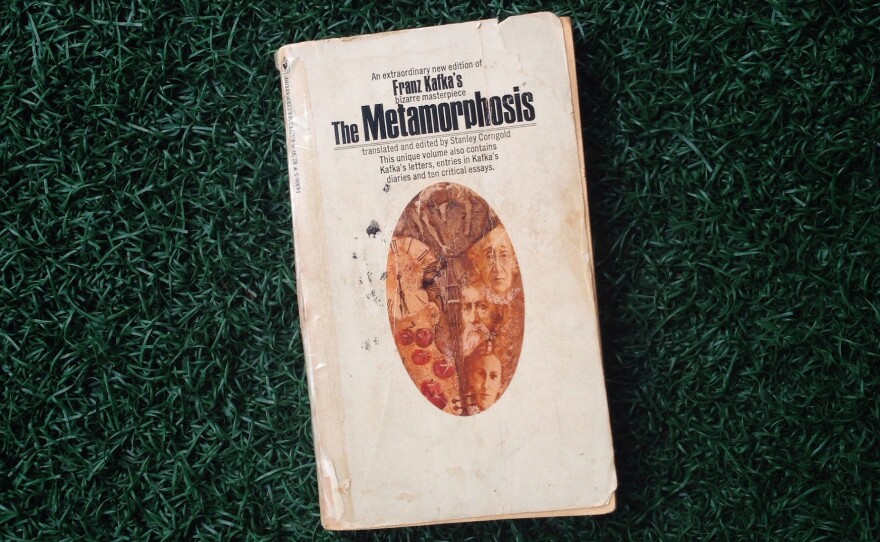

As readers everywhere revisit the masterpiece at its centenary, I find that the most enjoyable way to do so is to take in its beautiful absurdity as if for the first time: With a pen, underlining text and making note of lines and phrases that stand out. My favorite version of the text — if only because it was the one that came to me when I most needed it — is the 1972 edition, translated and edited by Stanley Corngold, that my uncle handed me that day in Bogotá.

The Metamorphosis was written while Kafka was working as an assessor at the Workers Accident Insurance Institute, a government agency that analyzed injuries caused by industrial accidents and administered benefits to those in need. And what he experienced in that position — from the failings of bureaucracy to the shortcomings of the law — helped inform his fiction. He continued to work at the agency for much of his life, until tuberculosis forced him to retire.

But perhaps even more than any office job, his father had a profound impact on the way Kafka approached life and writing. It's no secret that Kafka's father was a less than ideal father; he's long been described as a tyrant who possessed an awful temper and never encouraged his son in his creative pursuits. "You are unfit for life," Kafka wrote to him in 1919. The frustration that Kafka felt toward his present father closely resembled some of the anger that I felt toward mine, only in my case it was through his absence.

Had any of Kafka's work, from 'The Trial' to 'The Castl'e and 'Amerika' been tossed into the flames, I'm not sure where I'd be, actually.

As Kafka was dying in 1924, at the young age of forty, he demanded that his close friend Max Brod burn every last one of his remaining papers. But, as the story goes, Brod chose not to honor his friend's wishes, opting instead to publish a portion of the manuscripts. Needless to say, I'm glad the work survived. Had it not, had any of Kafka's work, from The Trial to The Castle and Amerika been tossed into the flames, I'm not sure where I'd be, actually. It's possible I'd be in jail or maybe high someplace terrible. That's damn depressing, sure, and you could even say dramatic. But it's all the way right and true.

Juan Vidal is a writer and critic for NPR Books. He's on Twitter: @itsjuanlove

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))