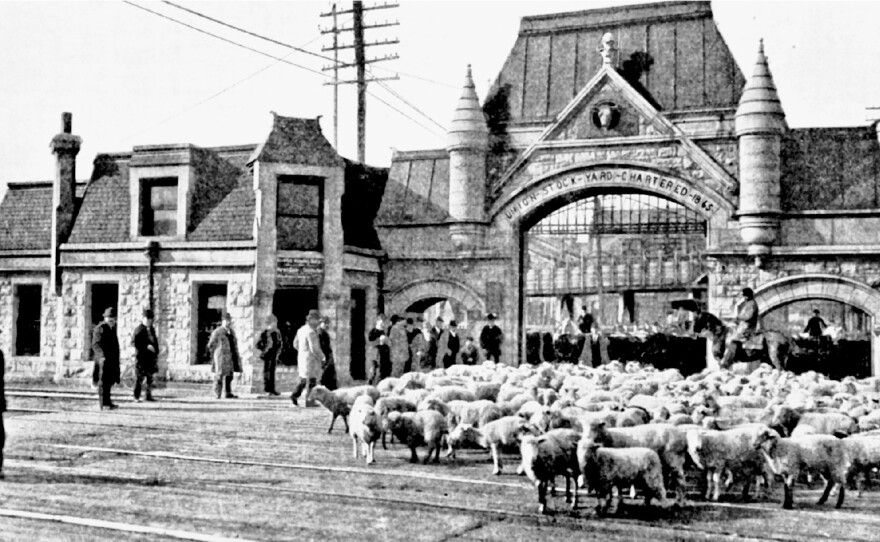

It's impossible to pinpoint the exact moment American's embraced industrialized food. But the first Christmas after the Civil War is a key date to note. That's when Chicago's infamous Union Stock Yard opened to the public in 1865.

"Its promoters clearly thought there could be no more appropriate way to observe a festive Christian holiday in the midst of America's capitalist hothouse than to open the greatest livestock market the world would ever see," writes Dominic A. Pacyga in his new book, Slaughterhouse: Chicago's Union Stock Yard And The World It Made.

"See" is the key word here. Because the new modern industry was quite a spectacle to behold, says Pacyga, and it was by watching it that Americans began to change their relationship to meat. We caught up with Pacyga by phone to talk about how Chicago instigated that transformation. Here's part of our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity.

Why were the Union stockyards so important?

The Union stockyards were so important because this mass industry really changed the way Americans, well, the way the world, thinks about food. Also it was sort of the beginning of mass industrialization, at least in Chicago. The use of assembly line techniques — or really, "disassembly" line techniques — began very early in Cincinnati, but they were used here in Chicago very effectively.

In the book, you mention that when the stockyards opened, they were quite a tourist attraction.

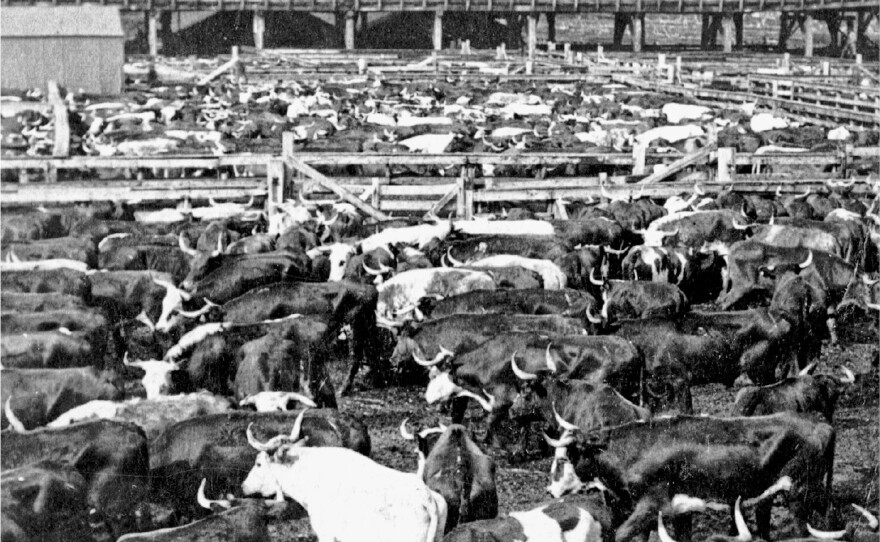

And remained a tourist attraction well into the 20th century. By the turn of the 19th century, about 500,000 [people] a year were coming to visit the stockyards and the packinghouses. We should keep the two apart. The stockyard was a livestock market: 450 acres covered with pens and railroad chutes and office buildings.

But the packinghouses adjacent to it were another several hundred acres of meat packing plants. And people would come and take a tour of both. They'd go through the stockyards, usually entering through the stone gate just west of Halsted Street, and then eventually end up in the packinghouses themselves.

At the very beginning, the tours were given by street kids, but eventually the packinghouses had organized tours with uniformed tour guides. You'd walk into a rather nice waiting room and were taken by the guides. There were galleries above the kill floors, so you could watch the whole process.

What exactly did people see when they toured the stockyards?

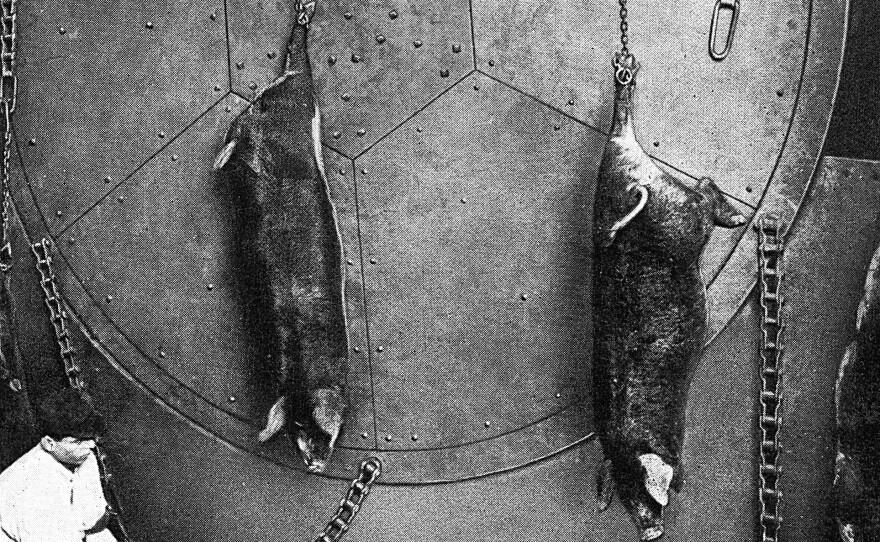

They saw just about everything. Hogs were driven to the roofs of the building, where they were allowed to cool down. And then they were brought onto the kill floor, about 12 or 13 at a time, where a shackler would shackle the hind leg. And then the hog would be lifted into the air by the Hurford Wheel, and they'd go to the sticker, who basically cut the hog's throat. Then it would pass onto an army of 150 men and women who would dress the hog. And then you were taken off to see the soap works, the hide rooms, through the whole thing.

Actually, it's kind of hard for contemporary people to think about 'why would you take children to see this?' But as late as the 1950s, grade school children in Chicago were taken to see the hog slaughter. It was the presentation of the modern. And the fact is that the presentation of the modern was both intriguing and frightening. It was a spectacle. It drew hundreds of thousands of people a year.

How did that "spectacle" or the "presentation of the modern" change the way people thought about their food?

In 1890 it took about eight to 10 hours for a skilled butcher and his assistant to slaughter and dress a steer on a farm. In Chicago, it took 35 minutes. Big packing houses were killing 1,500, 2,500 steers a day. They were killing 6,000 to 7,000, maybe even 8,000 hogs a day. And the same amount of sheep. It was this grand spectacle of something that was very common. I mean, if you grew up on a farm, you knew how to do these things. You knew where meat came from. Suddenly it's removed from everyday life. It's removed form the human experience.

Do you think that, because people were able to watch this spectacle, it actually helped bring about this change that separated us from where meat comes from?

Sure. It made it less personal. Those of us who live in cities don't have a personal relationship with the meat we eat. There's this separation. And it must have been absolutely fascinating to people in the 19th century to see this mass [of livestock] coming together. The Chicago Tribune called it "organized chaos." From 1893 to 1933 there were never fewer than 13 million head of livestock at the stockyards annually. Twice they peaked at over 18 million. Just a massive amount of animals. One author called it "man, meat, and miracle." It was actually the miracle of mass industrialization.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.