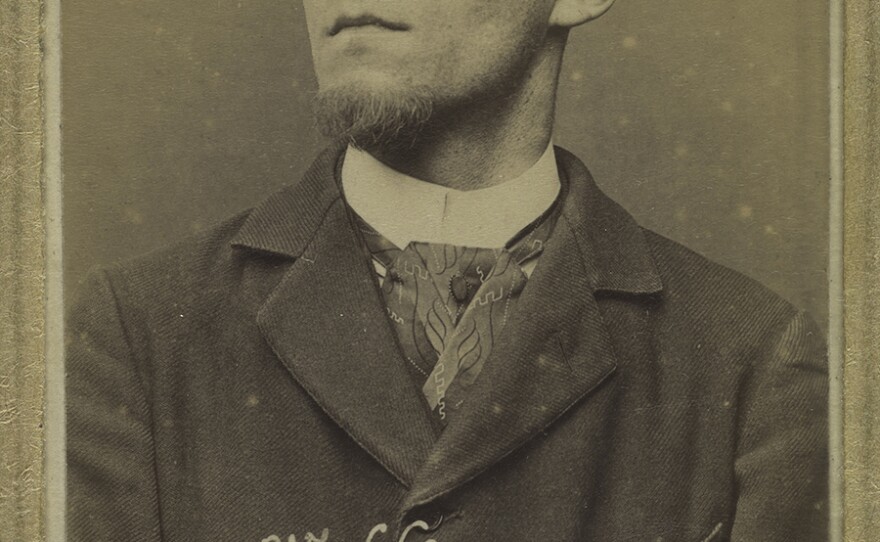

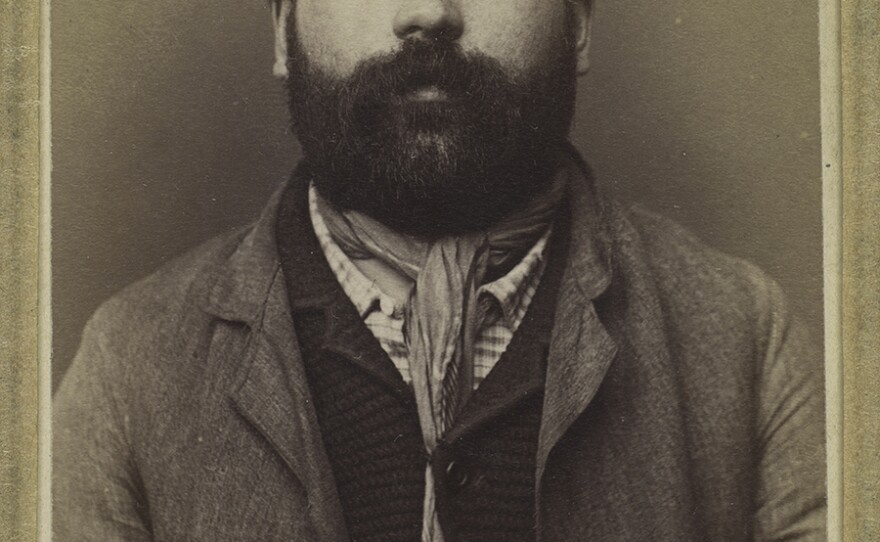

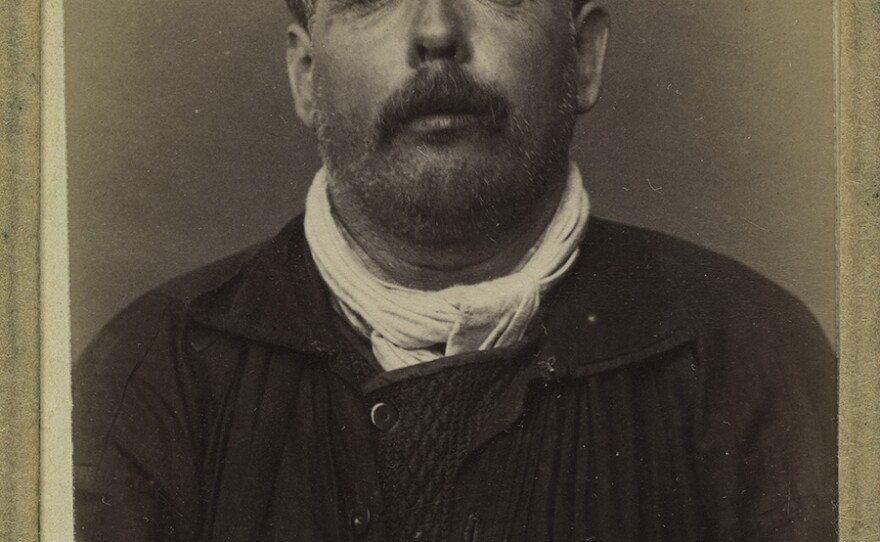

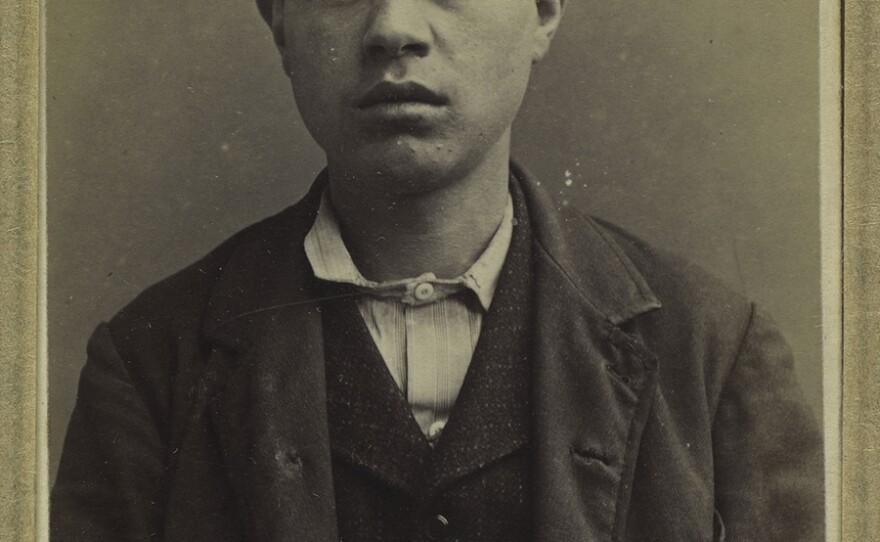

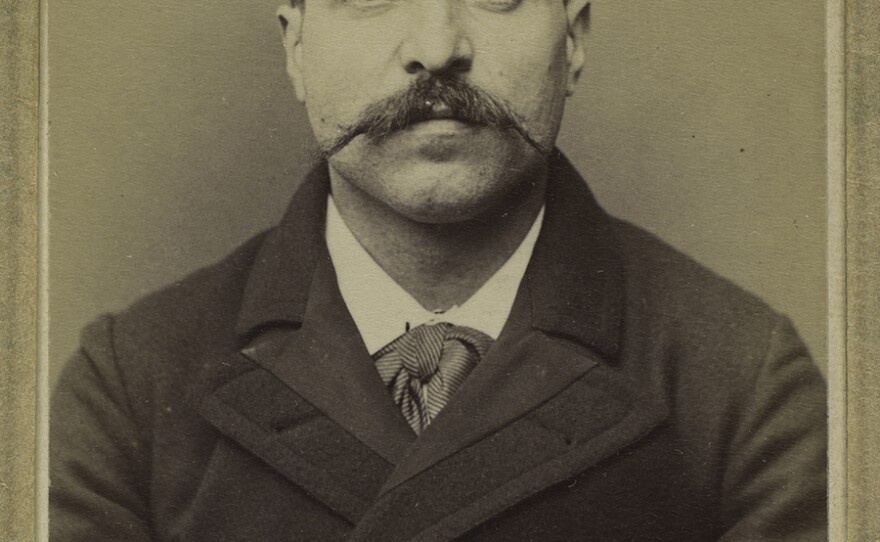

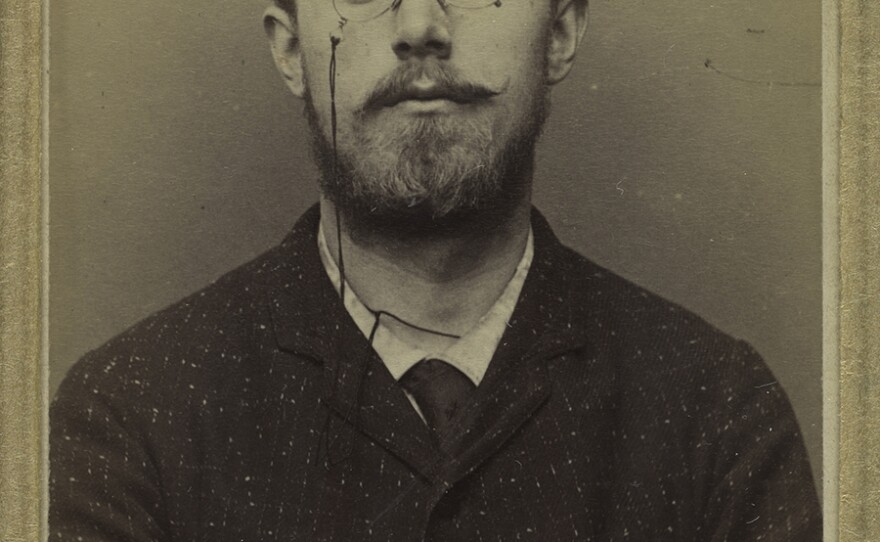

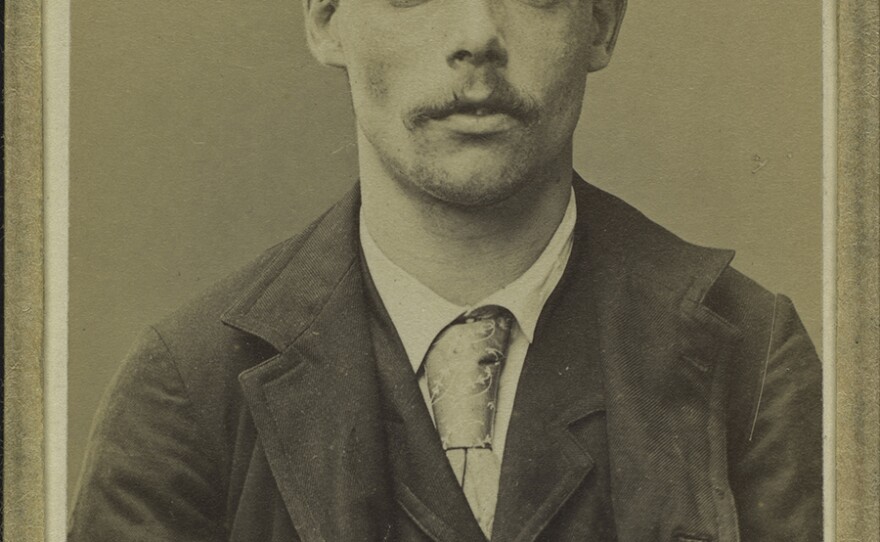

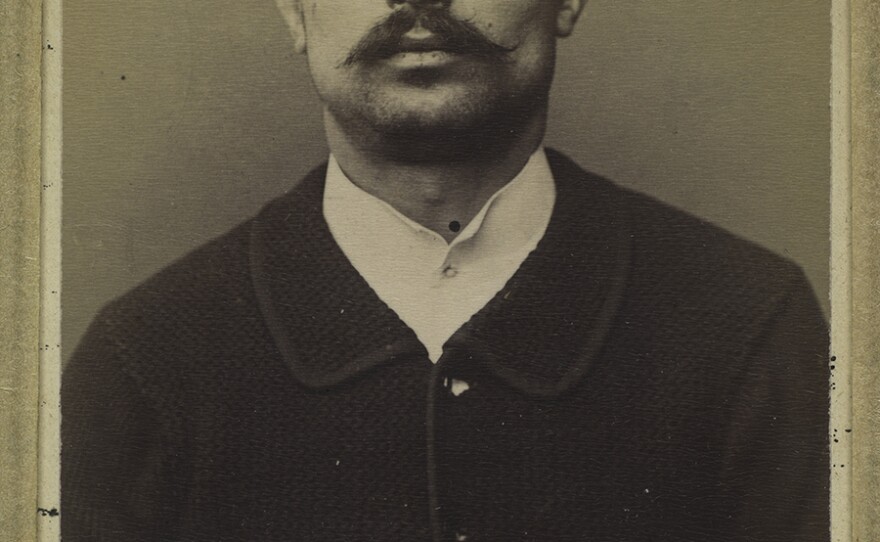

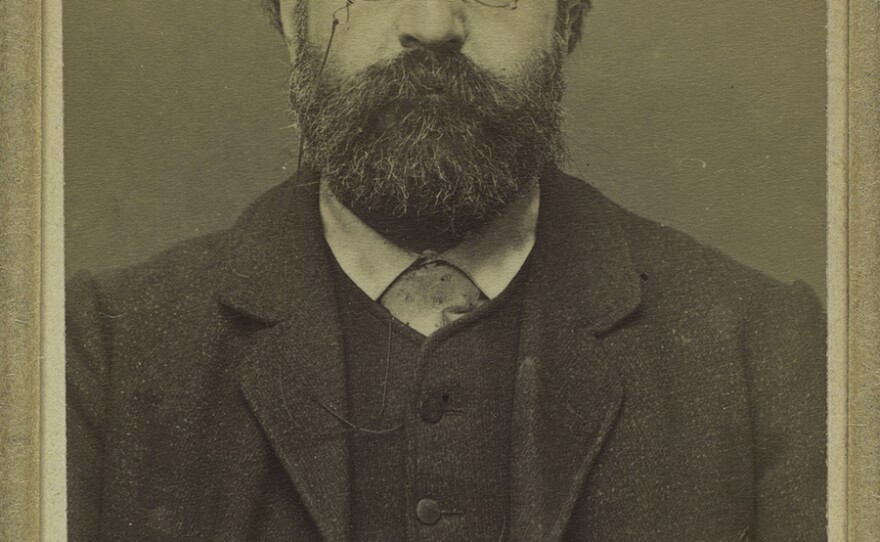

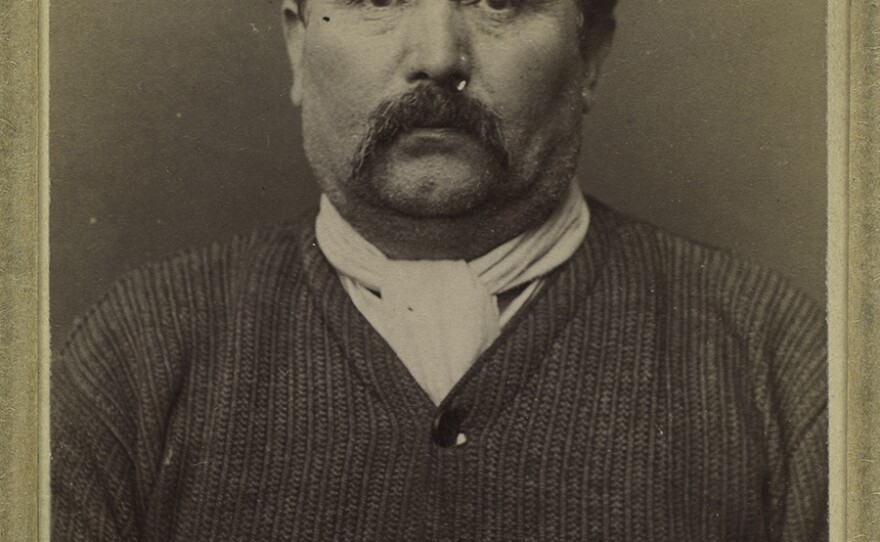

For more than a century, mug shots have helped police catch criminals. Those photos of a person's face and profile trace their roots to Paris in the late 19th century.

Now, some of the earliest mug shots ever taken are on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The black-and-white photos were once on the cutting edge of how police identified suspects.

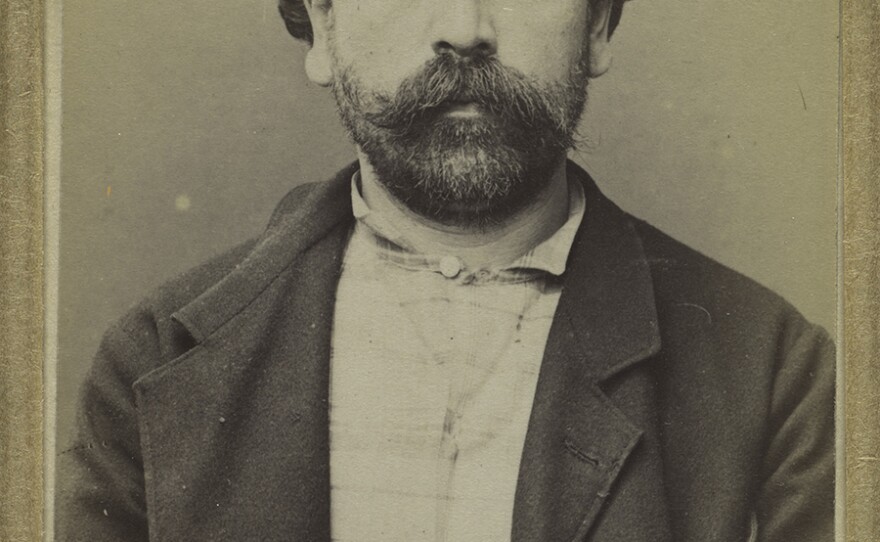

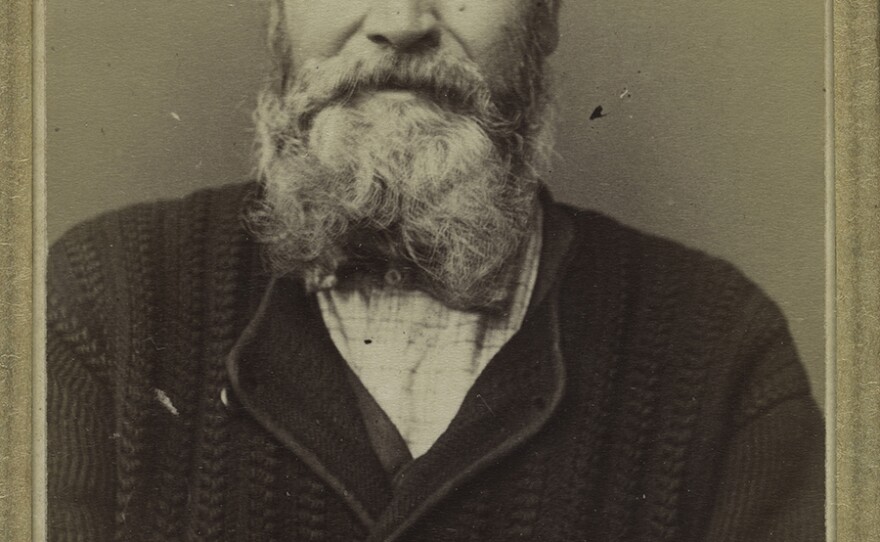

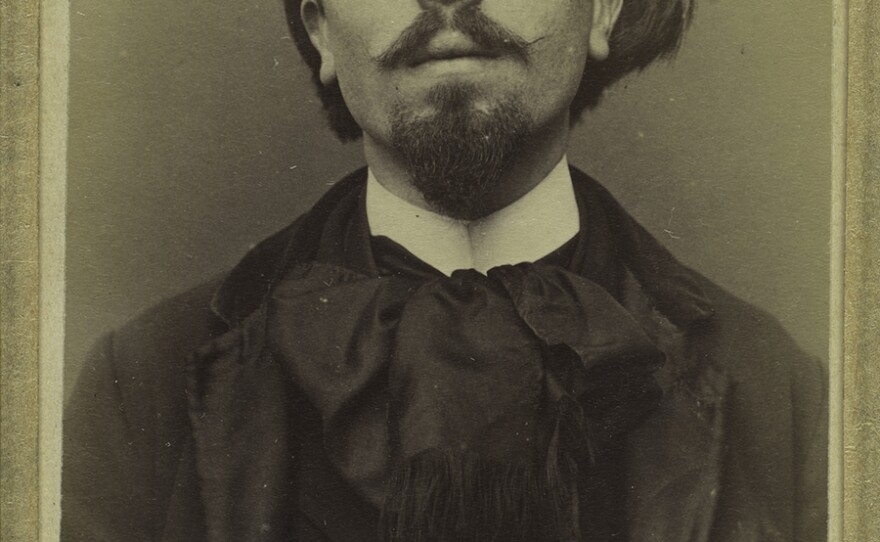

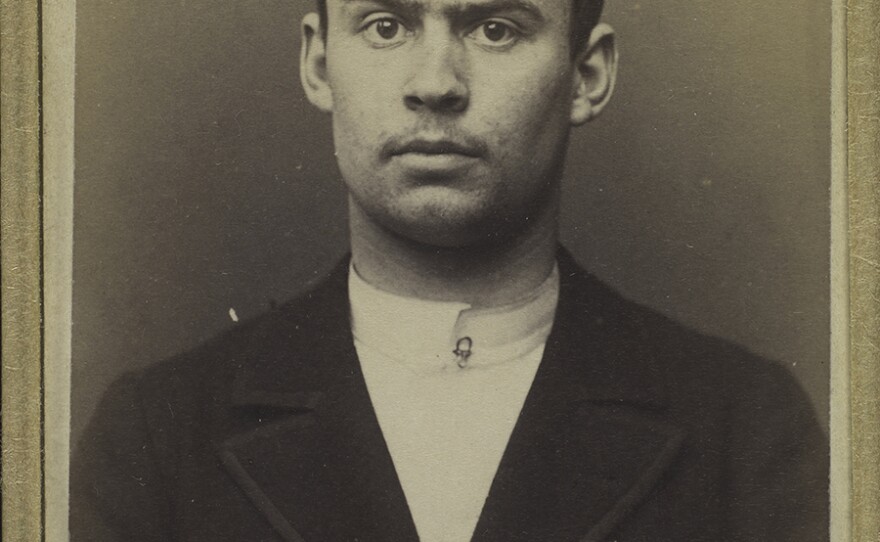

They were taken by a French criminologist named Alphonse Bertillon, and his techniques set the template that police use today.

Rise Of The Modern Mug Shot

Wilhelm Figueroa, director of the New York City Police Department's photo unit, says there are three parts of a mug shot the NYPD takes after arresting someone: the front view and both side views.

He estimates he has probably taken tens of thousands — and seen millions — of mug shots since he joined the department more than 30 years ago.

"No one looks like a criminal per se. There's nothing about a person's face that says, 'This person's a criminal,' " he says. "We're all capable of great good. We're all capable of being bad people."

And profile mug shots are capable of helping police tell similar-looking people apart.

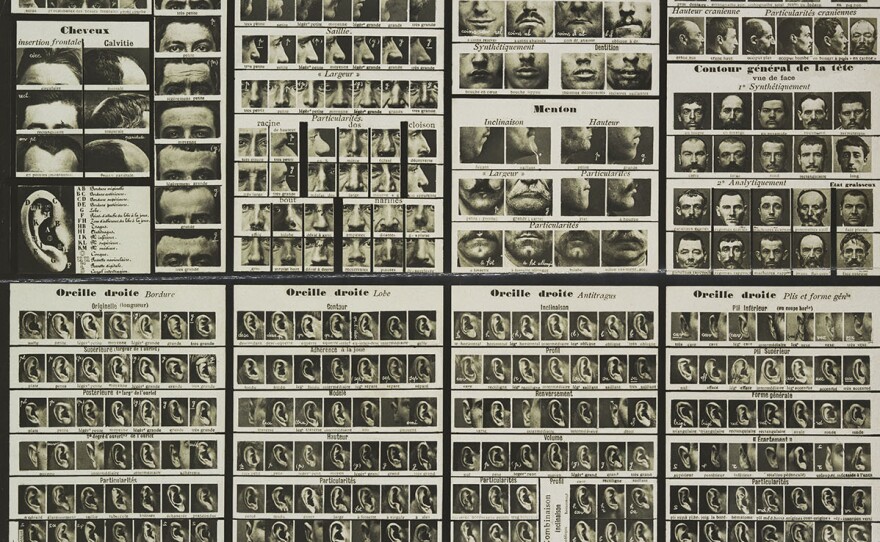

"Take 10 different people, take pictures of their ears and you'll be to identify each and every one of them because we all have different facets to our ears. Some of us have longer earlobes, some shorter, some thicker, some thinner," he says.

It's an observation that Bertillon championed back in the late 1800s. He went on to create a system for identification that the Paris Police Prefecture adopted in 1882, giving rise to the modern mug shot.

He wasn't the first to introduce mug shots to police, but he did standardize the way photos were taken and added the profile mug shot so police could zero in on a suspect's unique features.

"Men can grow facial hair to cover their chin, but you can't change the shape of your nose except through surgery. And you can't change the contours of your ear," explains Mia Fineman, one of the curators for the Met's new photo exhibition Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play, which features some of Bertillon's work.

The mug shots were part of a broader system of measuring and comparing body parts to help police departments organize thousands of criminal records. In 1884, Bertillon's system helped Parisian police identify 241 repeat offenders. His work became so famous that in Arthur Conan Doyle's The Hound of the Baskervilles, a client offends Sherlock Holmes by calling him "the second highest expert in Europe" — after Bertillon.

A Mug Shot Legacy

His reputation, though, faded as more police departments learned that fingerprinting was a simpler way to identify people.

Still, his style of mug shots became the standard. Jonathan Finn, a police photography expert who wrote Capturing the Criminal Image, says he is "still very much with us" today in other ways.

"Whenever you go through an airport or at a train station and anything else and somebody asks to see your identification document, that all has roots in the late 1800s and the work of people like Bertillon and his contemporaries," Finn says.

Figueroa says he thinks of Bertillon whenever he comes across an interesting mug shot.

"It could be an interesting curve of the ear, a unique tattoo. It could be a unique port-wine birthmark," he says.

Even in an age of DNA testing and iris scans, he says he doesn't think Bertillon's photo legacy is going anywhere.

"A victim still records the person had black hair, the person had a tattoo that said 'Mom' on their right shoulder. We still live in a very visual world," Figueroa says.

It's one that may have forgotten about Bertillon's name — but is still holding on to his mug shots.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.