Adam Summers used to trade Snickers bars to get free CT scans of dead fish.

He likes fish. A lot.

Summers is a professor at the University of Washington in the biology department and School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences.

"I've always been a fish guy," he says. "It's just been in my blood since I was as small as I can remember." Summers was a scientific consultant on Finding Nemo and did similar work with Finding Dory.

He describes himself as a biomechanist — he studies "how physics and engineering govern some parts of biology." Some of that refers to, for example, studying how humans could use ideas from the structure of a fish skeleton to design an underwater vehicle.

"A lot of what I do is in the realm of what's called biomimetics," Summers tells NPR. "I'm looking to the sea for inspiration, for biomimetics solutions to technical problems."

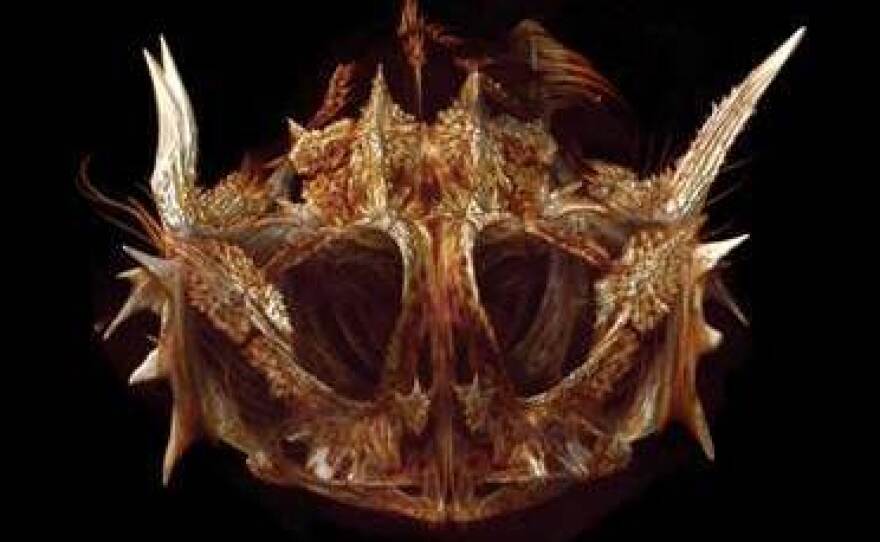

He's based on an island about 60 miles north of Seattle, at the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories. The lab is only a short walk from the water — from "the water's edge to the cutting edge," Summers says. As part of his work at the lab, his team is trying to make 3-D CT scans of all 33,000 varieties of fish.

So, why?

Researchers like Summers want to understand how fish work. To do that, he says, "one of the very, very useful things is to understand exactly what the skeleton looks like. It is shockingly complex. Your skull is just a few bones. Fish skulls are dozens and dozens of bones."

That's where the CT scans come in. The machines are usually used to see the insides of humans. Many years ago, Summers wanted to see the insides of fish.

"I would beg, borrow and bribe my way to getting good CT scan data," he says. "I would go with my pockets full of Snickers bars to a particular scan tech who worked at night and didn't mind if I showed up with a damp bag full of stingrays. And I would trade Snickers bars for free CT scans."

Eventually, private donors ponied up funds for a small CT scanner for the Friday Harbor lab, a move Summers called "transformative."

Now the goal is to create a digital library with 3-D images of all 33,000 species of fish. Summers says it can be done in about three years by scanning multiple fish at the same time.

"I love the idea of getting all this stuff up on the Web for anyone to access for any purpose," he says. "To allow the general public and every scientist out there to just download these data is fabulous."

In three months, he says the team has put up scans for more than 500 fish. He predicts the project will save money — he says research agencies frequently scan the same species more than once. Having the data open for anyone will eliminate any research overlap.

"Every aspect of fish is absolutely fascinating," Summers says. "It has just an unbelievable amount of information there to be picked out."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.