Three college-age scientists think they know how to solve a huge problem facing medicine. They think they've found a way to overcome antibiotic resistance.

Many of the most powerful antibiotics have lost their efficacy against dangerous bacteria, so finding new antibiotics is a priority.

It's too soon to say for sure if the young researchers are right, but if gumption and enthusiasm count for anything, they stand a fighting chance.

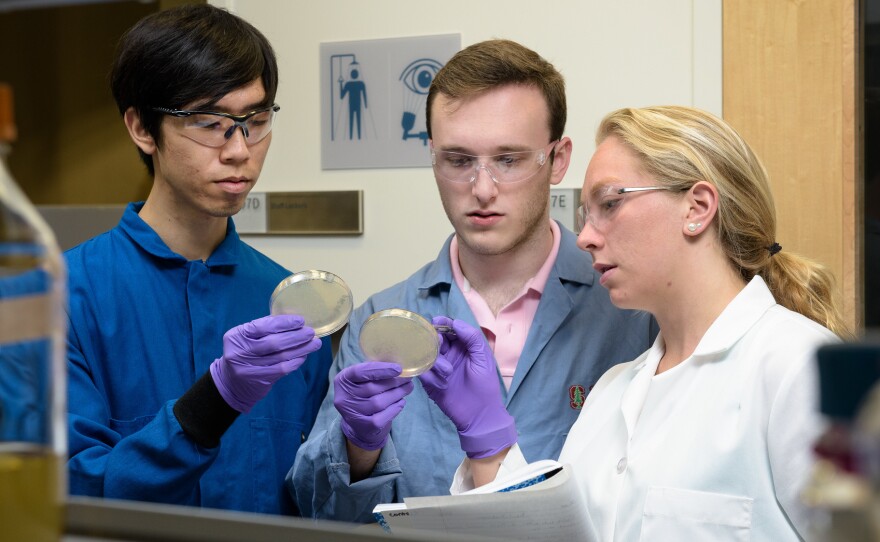

I met Zach Rosenthal, Christian Choe and Maria Filsinger Interrante in the lower level of the Shriram Center for Bioengineering & Chemical Engineering on the campus of Stanford University.

Filsinger Interrante just graduated from Stanford and is now in an M.D./Ph.D. program. Rosenthal and Choe are rising seniors.

Last October, Stanford launched a competition for students interested in developing solutions for big problems in health care. Not just theoretical solutions, but practical, patentable solutions that could lead to real products.

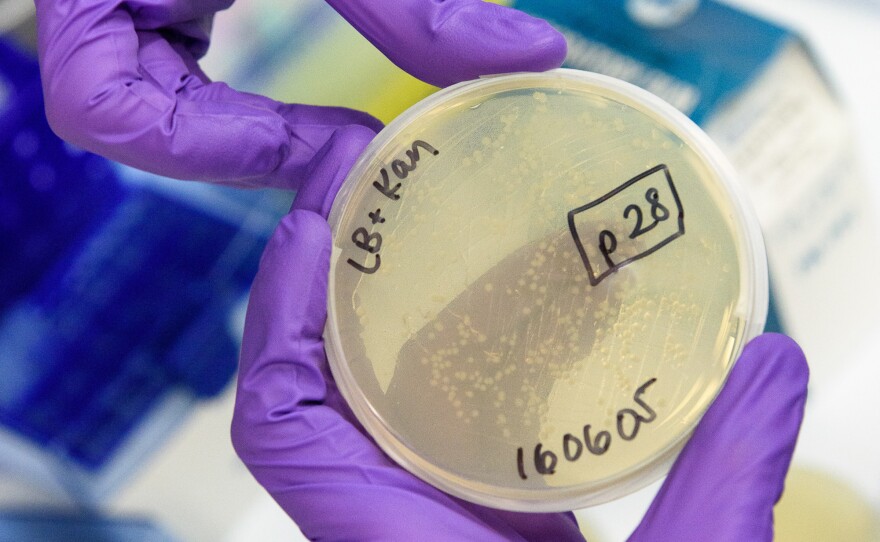

The three young scientists thought they had figured out a way to make a set of proteins that would kill antibiotic resistant bacteria.

They convinced a jury of Stanford faculty, biotech types and investors that they were onto something, and got $10,000 to develop their idea.

"And we want to see if our proteins are more effective at killing these resistant bacteria than what's currently available," says Filsinger Interrante.

Choe says there's a reason industry hasn't solved the antibiotic crisis.

"Big pharmaceutical companies aren't that interested in pursuing antibiotics," he says, "largely because the market size is small, and because bacteria develop resistance relatively quickly."

But these young entrepreneurs think they've licked the resistance problem.

"The way that our proteins operate, that if the bacteria evolve resistance to them, actually the bacteria can no longer live anymore," says Rosenthal. "We target something that's essential to bacterial survival."

Bacteria have managed to evolve a way around even the most sophisticated attempts to kill them, so I was curious to know more about how the proteins these young inventors say they've found worked.

"We're not able to disclose, unfortunately," says Filsinger Interrante. It's their intellectual property, she explains, that they hope will attract investors. "We think that our protein has the potential to target very dangerous, multidrug-resistant bacteria."

"I've been working in the field of antibiotics for the past 25 years and this is as good as any an idea as I've heard," says Chaitan Khosla, a professor of chemical engineering and chemistry at Stanford. He's also the director of a new program called ChEM-H, for Chemistry, Engineering & Medicine for Human Health, that's supporting the students' hunt for a new antibiotic.

But Khosla warns that many good ideas fall by the wayside, and even if the team's proteins clear the initial hurdles, it would be years or decades before there's a product ready to bring to market.

The trio are aware of the long odds. But for now, Rosenthal says they're going to give it all they've got, even it means working late into the night, after classes and other commitments are finished.

"I lose some sleep, but I love what I'm doing, so it's worth it," he says.

The team reports preliminary results for their new antibiotic proteins are looking good, so all that work may be paying off.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.