Doctors describe 16-year-old Sebastian DeLeon as a walking miracle — he is only the fourth person in the U.S. to survive an infection from the so-called brain-eating amoeba.

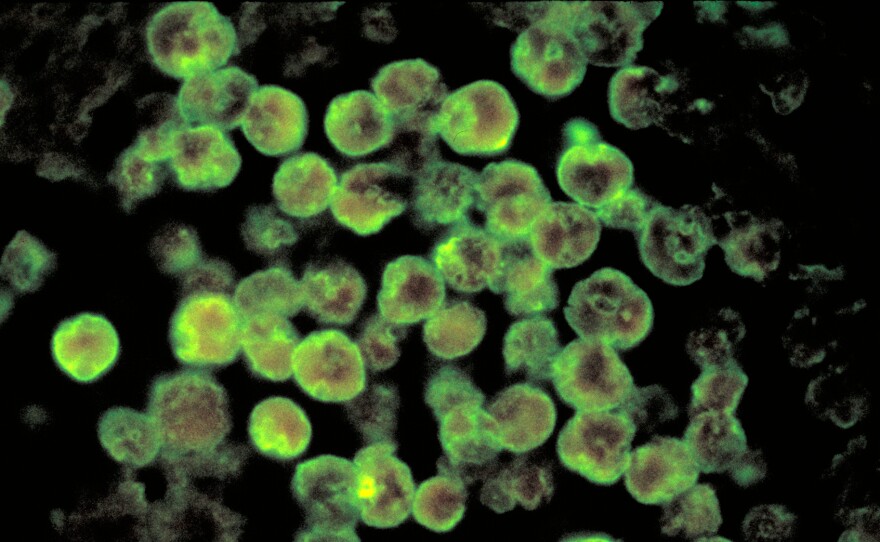

Infection from Naegleria fowleri is extremely rare but almost always fatal. Between 1962 and 2015, there were only 138 known infections due to the organism, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Just three people survived. This summer, two young people, one in Florida and one in North Carolina, became infected after water recreation. Only one had a happy ending.

DeLeon is a 16-year-old camp counselor. The Florida Department of Health thinks he got the infection while swimming in unsanitary water on private property in South Florida before his family came to visit Orlando's theme parks.

So many things had to go right for DeLeon to survive. On a Friday, he had a bad headache. The next day, his parents decided this was way more than just a migraine and took him to the emergency room at Florida Hospital for Children.

Doctors persuaded the family to do a spinal tap to rule out meningitis, even though he didn't have a stiff neck, the telltale symptom. Sheila Black, the lab coordinator, looked at the sample and assumed she saw white blood cells. But then she took a second, longer look.

"We are all detectives," Black said. "We literally had to look at this and study it for a while and watch for the movement because the amoeba can look like a white cell. So unless you're actually visually looking for this and looking for the movement, you're going to miss it."

That movement triggered the alarm: This was an amoeba case. And that's when the pharmacy reached out to a small Orlando drug company called Profounda, which has a drug called Impavido that was originally developed as a cancer treatment and approved by the FDA in 2016 to treat the tropical parasitic disease leishmaniosis. It has been used in several cases to treat amoeba infections as well.

Profounda CEO Todd MacLaughlin got the call from the pharmacy, but he was out of town so his son drove the drug to Florida Hospital.

"Within 12 minutes he had picked up the product and was on the way to the hospital," MacLaughlin said. "Everybody was in the right place at the right time."

DeLeon was given the drug along with others. Doctors put him into a coma and lowered his body temperature to give the drugs time to work and slow the infection.

Dr. Humberto Liriano was emotional talking about the experience. They knew the odds were not in DeLeon's favor when he was placed into a coma.

"The family when they came to me, immediately within four hours, I had to tell them to say their goodbyes," Liriano says. "I had to tell them, 'Tell him everything you want to tell your child, because I don't know from the time I put him to sleep to the time I take the tube out, [if he will] wake up.' "

DeLeon's mother, Brunilda Gonzalez, thanked doctors at a press conference.

"We are so thankful that God has given us the miracle through this medical team and this hospital for having our son back and having him full of life," Gonzalez said. "He's a very energetic adventurous, wonderful teen. We're so thankful for the gift of life."

Central Florida has coped with amoeba infections before, including the death of Jordan Smelski, who died at the same hospital where DeLeon was saved. Smelski's parents started a foundation to raise awareness of the disease in the medical community and to advocate for hospitals to stock the drug in case of an infection.

Profounda says seven hospitals have taken it up on stocking the drug at no cost, charging them only when the drug is used. The drug costs $48,000 for a full round of treatment. MacLaughlin said the company will provide the drug free if someone doesn't have insurance.

DeLeon will soon head to South Florida for rehab, and doctors are optimistic he'll make a full recovery.

But in North Carolina, an 18-year-old Ohio woman died from the amoeba in mid-June, stoking fear in the community. She had been rafting at the U.S. National Whitewater Center in Charlotte, which is among a handful of facilities in the country that have man-made rapids coursing through concrete channels. Its CEO, Jeff Wise, pointed out the lower part of the channel in mid-July.

"This is the bottom pond," he says, "where all of the water in our essentially 12 million-gallon system rests while it's ready to be pumped back up into the top pond, where it'll float back down through the channels."

But there was no whitewater between late June and Aug. 10, because CDC tests found the amoeba after the woman died.

Mecklenburg County Health Director Dr. Marcus Plescia encouraged people to keep perspective.

"This organism, Naegleria fowleri, is actually quite a prevalent or commonly occurring organism in open bodies of water," he said. "We find it in lakes. We find it in ponds. It's very common for people to come into contact with, but it's very uncommon for people to develop this kind of infection with it."

It's harmless if swallowed, because stomach acid kills it. But if it's in water forced up the nose, it can cause the brain infection, which is difficult to diagnose and treat.

The Whitewater Center uses city water that it treats with UV radiation, a filtration system and some chlorine. Still, it's a large, open body of water, and exists in a regulatory no-man's land because it's neither swimming pool nor local river or lake.

North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory said the state should re-examine whether the center should be treated like a swimming pool. But testing for the amoeba is not part of swimming pool regulations, because chlorine used in pools is effective at killing it. And the county and the state don't have the ability to test for it. It's usually up to the CDC.

As part of its lease agreement with the county, the center does weekly tests for common contaminants such as fecal coliform bacteria.

County health leaders point out that people are much more likely to die from drowning or boating accidents in area lakes and rivers than they are from Naegleria fowleri. In fact, there have already been at least eight of those deaths in the greater Charlotte area this summer.

But people just don't get as worked up about those. David Ropeik, a risk management consultant in Concord, Mass., explains why.

"We worry about things not only based on the likelihood of them happening but the nature of the experience itself," Ropeik says. "The odds may be low of brain-eating amoeba eating your brain, but the nature of a brain-eating amoeba eating your brain sounds pretty scary, doesn't it?"

Ropeik is the author of How Risky Is It, Really? He says the media coverage of rare risks is part of the problem.

"Anything that makes a risk feel scarier like, 'This is the zombie amoeba!' is going to subconsciously interest journalists as something that will get people's attention," he says. "Because the viewer, reader, listener is likely to pay attention to a story that could portend their death."

Dr. Jennifer Cope, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the CDC, said 11 out of 11 tests for the amoeba were positive at the rafting center, which does sound alarming. She called that significant but noted this is the first time the CDC has encountered the amoeba in this type of setting.

Whitewater Center CEO Wise says roughly 1.5 million people have rafted there over the past decade, and this is the first health issue it has had tied to what's in the water.

The CDC says there are ways to make the water less conducive to the amoeba's growth, including bulking up the amount of chlorine. The Whitewater Center worked with consultants to figure out a more effective way of doing that, and it reopened this month with a revamped chlorination system. So far, county health leaders say it is working the way it is supposed to.

This story is part of a reporting partnership with NPR, local member stations and Kaiser Health News.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.