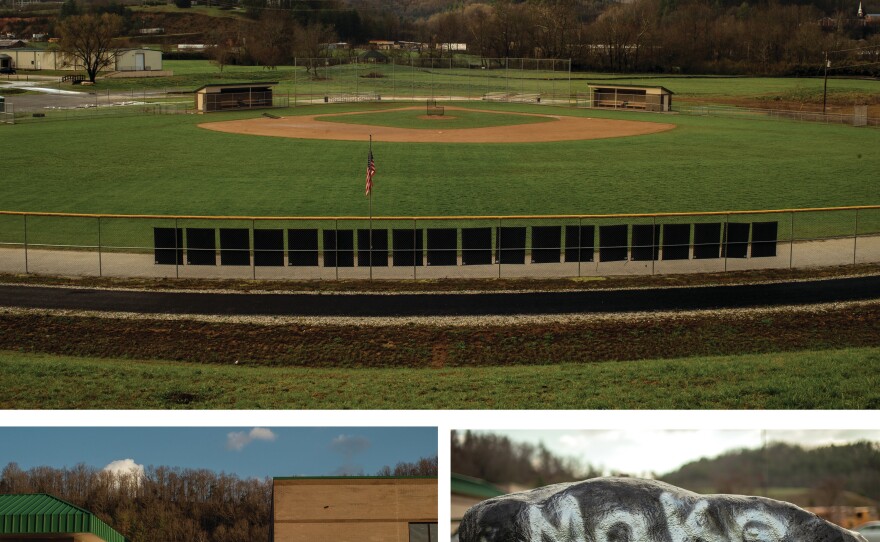

Robbinsville High School sits in a small gap in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. Green slopes dotted with cattle hug in around the school before they rise into a thick cover of pine trees.

David Matheson is the principal here. And he's the only high school principal in the state who still performs corporal punishment. At Robbinsville, corporal punishment takes the form of paddling - a few licks on the backside Matheson delivers with a long wooden paddle.

North Carolina state law describes corporal punishment, as "The intentional infliction of physical pain upon the body of a student as a disciplinary measure."

Robbinsville High School's policy allows students to request a paddling in place of in-school-suspension, or ISS. Last year, 22 students chose it.

"Most kids will tell you that they choose the paddling so they don't miss class," Matheson says.

One of those students is Allison Collins. She's a senior now and says she chose to be paddled her sophomore year after her phone went off in class. She describes it as, "My first time ever being in trouble."

Collins went to the assistant principal's office where she was told she had a day of in-school-suspension. Collins told Principal Matheson she'd rather take a paddling and so he called her father to get permission.

"And my dad was like, 'Just paddle her,'" she says. "Because down here in the mountains, we do it the old-school way."

That's the policy here. Principal Matheson paddles a student only if he gets permission from their parent. And, he says, very few parents opt out. Matheson grew up here and went to school with a lot of his students' parents. "It's something that the family decides," he adds.

Nationwide, it's not unusual for parents to support the use of corporal punishment as a form of discipline. Recent surveys show about 75 percent of Americans believe it's sometimes necessary to spank a child.

"I think it goes back to traditional values," says Cheri Lynn, a Robbinsville parent who substitutes as a band teacher and coaches the school's shooting team. "A lot of parents still hold to the traditional values of corporal punishment. They use it at home, and so the school is an extension of home."

In a classroom down the hall, Beau Cronland, a student teacher, says he didn't know the school used corporal punishment until he sent one of his freshman to the office for talking. "Kids talk," he says, "I don't think they should get spanked for it, or paddled."

Tom Vitaglione, of the child-advocacy group NC Child, says for years he's been sending school leaders research papers showing corporal punishment leads to bad outcomes for students: higher drop-out rates, increased rates of depression and substance abuse and increased violent episodes down the road.

Principal Matheson says he's seen that research, but he still believes paddling is an effective form of discipline. "I think if more schools did it, we'd have a whole lot better society. I do, I believe that."

Vitaglione takes issue with that: "When it gets to schools, we now have an agent of the state hitting a child," he says. "And we don't believe that should happen."

When he started this work, more than thirty years ago, thousands of children in North Carolina were struck each year. Now, Robbinsville High is one of just a few schools that still use it. The latest numbers show about 70 students were paddled in the state last school year.

A recent investigation by Education Week shows that in the 2013-2014 school year, about 110,000 students were physically punished nationwide. That's in part because in some states, including Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and Texas, tens of thousands of students are paddled every year.

Child advocates are working toward zero paddlings in North Carolina. They're asking state legislators to outlaw the practice in schools for good. That's happening nationwide, too.

As NPR Ed reported in December, dozens of groups, including the National PTA, Children's Defense Fund and American Academy of Pediatrics signed a letter of their own, supporting an end to corporal punishment.

Copyright 2017 American Homefront Project. To see more, visit American Homefront Project.