A study designed to test the effectiveness of a controversial practice known as "abortion pill reversal" has been stopped early because of safety concerns.

Researchers from the University of California, Davis, were investigating claims that the hormone progesterone can stop a medication-based abortion after a patient has completed the first part of the two-step process.

For the study, the researchers aimed to enroll 40 women who were scheduled to have surgical abortions. Before their surgical procedures, the women received mifepristone, the first pill in the two-medication regimen that's used for medical abortions. The women were then randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or progesterone, which advocates claim can block the effects of mifepristone.

But researchers stopped the study in July, after only 12 women had enrolled. Three of the women required ambulance transport to a hospital for treatment of severe vaginal bleeding.

The researchers decided the risk to women of participation was too great to continue with the study. The study was unable to show what, if any, effectiveness progesterone has in reversing a medical abortion.

The results raise concerns about the safety of using mifepristone without taking misoprostol, the second step in the medication-based abortion regimen.

Advocates for abortion pill reversal have succeeded in having it written into law as an option to be discussed in mandatory pre-abortion counseling in several states, including Kentucky, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

Opponents have said there wasn't sufficient evidence to support the approach. Now, there's evidence that it could cause harm.

"Encouraging women to not complete the regimen should be considered experimental," says Dr. Mitchell Creinin, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis and the lead researcher on the study. "We have some evidence that it could cause very significant bleeding."

The results of the trial were published online Thursday in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology.

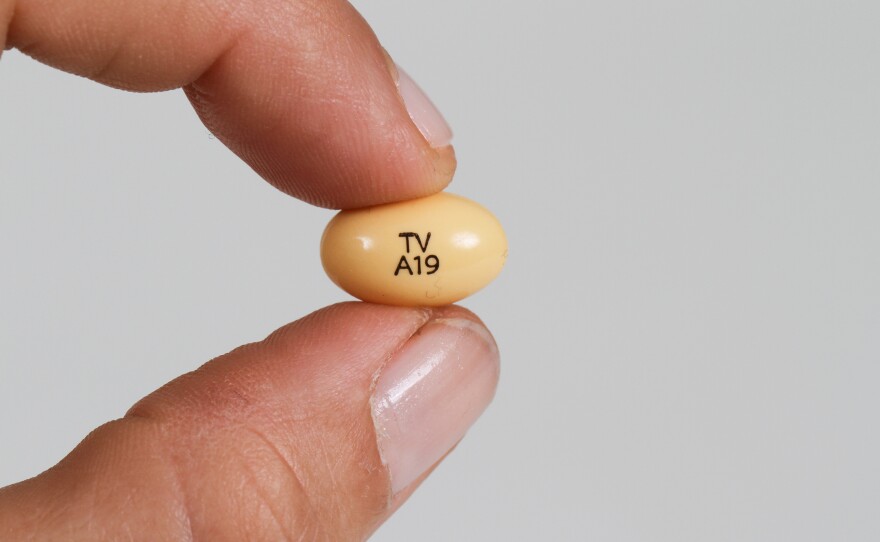

Medication-based abortions use a combination of two medicines — mifepristone and misoprostol — that patients usually take 24 hours apart. Mifepristone is a progesterone blocker. Misoprostol makes the uterus contract. Studies suggest that 95% to 98% of women who take both drugs in the prescribed regimen will end their pregnancy safely.

Proponents of the abortion-reversal treatment offer the hormone progesterone to patients after they have taken mifepristone but have then decided they don't want to complete the abortion. A group of researchers published a small case series about the protocol, claiming it prevents the abortion from taking place.

The research has been criticized for having serious methodological flaws. Most OB-GYNs — including the professional group the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists — oppose the practice, saying it's "not supported by science."

At least seven states, however, legally require abortion providers to tell patients about progesterone treatment for stopping a medication-based abortion midway through.

This advice, Creinin says, may put patients at risk for life-threatening bleeding.

"It's not that medical abortion is dangerous," he says. "It's not completing the regimen, and encouraging women, leading them to believe that not finishing the regimen is safe. That's really dangerous."

Although Creinin acknowledges that his study was limited by its premature termination and small sample size, he hypothesizes that taking mifepristone without misoprostol may be especially risky later in the first trimester of pregnancy. All three patients with severe bleeding were at least 56 days into their pregnancies.

The women who experienced hemorrhage included one who received progesterone and two who received a placebo. Of the remaining participants, two left the study because of side effects and completed their planned surgical abortions.

Women in both the progesterone and placebo groups had some evidence that their pregnancies continued. Four patients who took mifepristone and then received progesterone had pregnancies with cardiac activity on ultrasound. Two patients who got the placebo also had gestational cardiac activity.

Creinin says that because the study was cut short, it wasn't big enough to answer the question it set out to. There simply aren't enough data, he says, to know if the progesterone treatment is effective at preventing a medication-based abortion from taking place.

"Does progesterone work? We don't know," he says. "We have no evidence that it works."

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.