COVID-19 cases in California prisons and jails began to dramatically surge late last year, but there is no way to get an accurate picture of the pandemic inside these facilities because officials use different approaches to count in-custody deaths tied to the coronavirus.

Using public records, inewsource uncovered reporting mistakes and delays in Southern California and at the state level in tracking inmate deaths from the virus, including in San Diego County. These issues have led to some deaths going uncounted.

Shared housing makes jails and prisons especially susceptible to the spread of COVID-19. That’s why public health officials say accurate data on coronavirus cases and deaths is needed to make sure adequate health care standards are in place to protect inmates and those working in these facilities.

The problem, in Dolovich’s view, comes in part from corrections officials wanting to hide issues within their facilities.

“This is an urgent public health matter. … You can’t effectively respond to a public policy crisis when you are keeping secrets from the people who need to plan,” she said.

Dolovich, who runs a national inmate COVID-19 data tracker, believes coronavirus cases and deaths linked to jails and prisons are “dramatic undercounts.” The official numbers are “the floor but not anywhere near the ceiling,” she said.

Jails and prisons are public institutions run by public servants, Dolovich said. “It’s their obligation to be as transparent as possible,” she said.

In a review of COVID-19 inmate deaths tied to San Diego County, inewsource found public officials have inconsistent tracking standards, which complicates how to manage the public health threat in state prisons and local jails.

Here are some examples:

- The San Diego County Sheriff’s Department has not yet counted or reported to the state the first known COVID-19 death linked to one of its jails. Edel Loredo, 62, died Nov. 21 at the Sharp Chula Vista hospital. The county public health department appears to include him in its coronavirus totals, but the sheriff has not reported his death to the state’s jail oversight board.

- Rodney Beasley, 49, was incarcerated at Chuckawalla Valley State Prison in Blythe before dying on Sept. 14 at Tri-City Medical Center in Oceanside. He appears to be uncounted by Riverside and San Diego counties but counted by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as the 60th death from the virus among prison inmates.

- Timothy Morales, 45, was incarcerated at the Chuckawalla prison before dying Oct. 4 at Tri-City Medical Center. Morales also appears to be uncounted by Riverside and San Diego counties but counted by the state. A death matching his details is the 69th COVID-19 death among prison inmates.

- Victor Dominguez, 68, was incarcerated at Chuckawalla before dying Nov. 24 at Tri-City Medical Center. Dominguez also appears to be uncounted by Riverside and San Diego counties but counted by the state. Prison inmate COVID-19 death No. 85 matches his details.

inewsource discovered the inmate deaths by combing through hundreds of pages of county medical examiner records and death certificates, and reviewing government lists with no names but details such as date of death, age and race. There is no way to know if all inmate deaths in the county were counted, so there could be more.

When deaths are not accurately and promptly captured and assigned to the place where the illness occurred, experts who monitor inmate fatalities say it complicates disease management, can cause resources to be misdirected, and puts inmates, staff and the public at risk.

Inmate death numbers misleading

In two counties – San Diego and Orange – officials have said they count COVID-19 inmate deaths by the residence of the decedent as listed on the person’s death certificate, not where the death occurred.

“In general, a person who dies in custody and has an out-of-county address listed on a death certificate will not be counted in COVID-19 death totals provided by the County,” San Diego County spokesperson Michael Workman said in an email response to questions from inewsource.

Bryan Sykes, a criminology professor at UC Irvine who studies prisoner mortality rates across the country, called it “deeply problematic” to count inmate deaths based on out-of-county home addresses listed on death certificates.

“Deaths should really be recorded in the county in which they didn’t have adequate health provisions in order to prevent that death. And that’s also where the person more than likely contracted it,” Sykes said.

Obscuring those details creates a false sense of safety for jail staff and inmates, he said.

“You’re placing other people who are in custody at greater risk of contracting the disease through an inadequacy of policy and intervention,” Sykes said.

The risk also extends to the larger community, said Naomi Sugie, another UC Irvine criminology professor who is working on a project to document the pandemic in California prisons.

While many people assume that what happens inside incarceration facilities doesn’t affect those outside, that’s not the case, Sugie said. Local economies as well as the family and friends of inmates are impacted when virus cases and deaths increase, she said.

“The reality is that these systems are so connected to the fabric of our lives,” Sugie said.

She emphasized the need for better tracking of COVID-19 cases and deaths within California jails and prisons. “The fact that it’s so difficult to understand who has died from COVID is really so shocking,” Sugie said.

Some counties not capturing all inmate deaths

The state Department of Public Health has a 2013 handbook that outlines how inmate death certificates should be filled out. It states that if an inmate has been incarcerated for a year or more, the address of the facility should be listed as their place of residence.

But in practice, public records may contain errors. Incarceration facilities are not always noted on death certificates and mistakes can pop up in other places. In one COVID-19 death inewsource reviewed, the wrong prison location was listed in medical examiner records.

That’s what happened to Chuckawalla inmate Beasley. Although incarcerated in Riverside County, his cause of death report described him as an inmate at the Richard J. Donovan state prison in Otay Mesa, where he had not been held since 2013. Tri-City hospital provided the wrong prison information, a manager in the Medical Examiner’s Office said.

Some local jurisdictions do count inmate deaths based on where they were incarcerated, not the home addresses listed on death certificates. Los Angeles County follows this approach. A spokesperson for Long Beach, which keeps its own COVID-19 death tally within Los Angeles County, confirmed the city follows the same policy.

Because not all jurisdictions count deaths in the same way, it can cause problems.

Death certificates are created in the county where a person dies. If that county never shares that information with the home county, the death can go uncounted.

And the pandemic has challenged officials to manage and update data much faster than in the past. In San Bernardino County, for example, inmate deaths from the coronavirus are typically added to the county’s public death count list within eight weeks after the person died. In pre-pandemic times, it might take six months to verify a death, said Diana Ibrahim, interim contact tracing program manager for the county’s public health department.

“The public wants to know what’s happening, so we’re trying to get the information out as quickly and as accurately as possible,” Ibrahim said. “But it does take time to get all the information and put the pieces together to determine whether or not it was actually a COVID death, and whether or not we’re in alignment with the state.”

Prison death tracker doesn’t always match local data

inewsource found some instances where state and county data on inmate deaths were in conflict.

In Riverside County, as of Jan. 15, a public health spokesperson said the county had six COVID-19 deaths at its three state prisons. But the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation listed 11 deaths for the same period. County death numbers and the state’s count did not match at any of the three facilities: Chuckawalla, Ironwood State Prison in Blythe and the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco.

Jose Arballo Jr., a Riverside County public health spokesperson, dismissed questions about the discrepancies, saying the county was extremely busy with the vaccine rollout and probably did not have anyone investigating the miscounts.

“I don’t know why we have the difference,” Arballo said. He acknowledged there have been issues with the numbers from the state not matching Riverside County’s death counts.

In San Bernardino County, public health officials also provided COVID-19 death counts that did not match the state’s prison tracker. As of last week, one death that the state counted at the California Institution for Men in Chino could not be accounted for by county public health officials. In all, according to state numbers, 27 inmates have died there of the virus.

In San Diego County, 16 virus-related inmate deaths have been recorded at the Donovan prison, according to the state. As of Tuesday, the county was only including nine in its death total, though a spokesman said others would be added once investigations are completed.

Cases at Donovan went from two to 713 in the first three weeks of December, when they peaked. Inmates there have told relatives the prison lacks proper COVID-19 safety precautions like hand sanitizer.

Liz Gransee, a spokesperson for the California Correctional Health Care Services, which oversees the state prison tracker, would not answer questions from inewsource about the number differences other than to say the data the state uses comes from patient registries and the agency’s electronic health records.

“How we track our data is not connected to county data,” she said in an email.

Statewide, the tracker shows 192 prison inmates have died of COVID-19 as of Wednesday.

On a ventilator and in jail custody

COVID-19 cases tied to the virus have surged in San Diego County jails since November.

The Sheriff’s Department reports 36 active cases as of Monday, with more than 1,100 county jail inmates having been infected since the pandemic started.

But more than two months after the Nov. 21 death of the first known county jail inmate documented as dying from COVID-19, the Sheriff’s Department has yet to announce or count the fatality. The department also has yet to report the death to the state’s jail oversight board that provides the public with the only statewide tracker of COVID-19 cases and deaths among county inmates.

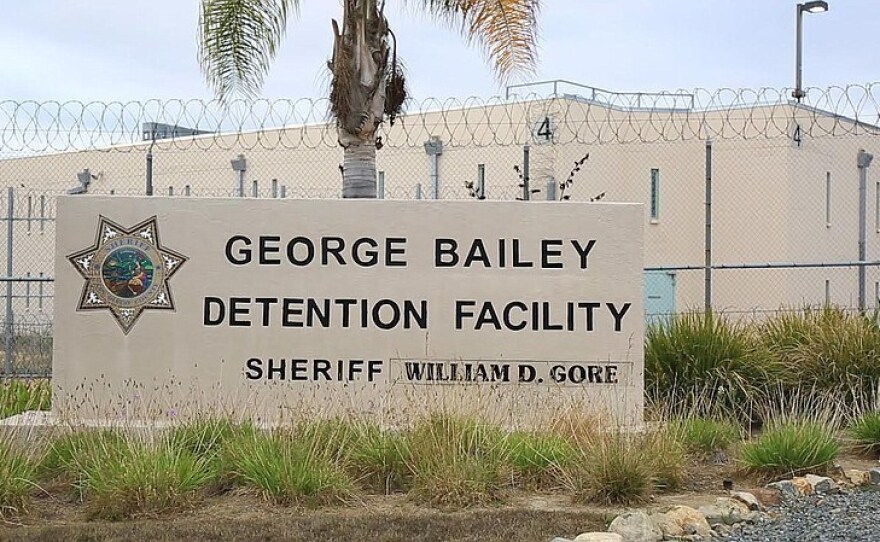

Edel Loredo had been jailed at the county’s George Bailey Detention Center in Otay Mesa before being transferred to Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center, where he was hooked to a ventilator before he died.

Based on his date of death, age and other identifiers, he appears to be No. 990 on the county’s COVID-19 death list, yet the Sheriff’s Department reports it has had zero inmate deaths from the virus. A sheriff’s spokesperson said the delay in reporting the death is because investigators have not yet received Loredo’s medical examiner’s report. That’s needed to complete their investigation and for them to announce his death, the spokesperson said.

The Sheriff’s Department did not respond to a question asking how many inmate deaths connected to the virus are under investigation. Loredo’s daughter said his family believes he wasn’t given proper medical treatment at the jail and was transferred to the hospital too late in his illness.

Kathleen Howard, executive director of the Board of State and Community Corrections, which regulates jails in California, defended the Sheriff Department’s delay in reporting the death to her agency. Various reviews can bog down the reporting time, she said.

Because of that, the agency’s COVID-19 tracker for county jails doesn’t accurately reflect how the pandemic is affecting these facilities. As of mid-January, more than a dozen counties across California were not submitting data on a weekly basis.

Earlier this year, criminal justice advocates criticized the jail oversight board for failing to collect basic COVID-19 data. Following the public pressure, the board began publishing data in July.

The scrutiny came after The Sacramento Bee and ProPublica published a yearlong investigation into dangerous California jail conditions and after Gov. Gavin Newsom called on the jail oversight board to improve its transparency.

“I think everybody’s doing the very best they can do under difficult circumstances,” Howard told inewsource, adding that she believes accurate COVID-19 tracking of county inmates is ultimately the responsibility of local public health departments.

In Loredo’s case, his daughter got the call a few days before Thanksgiving that he was losing his COVID-19 fight. Virgen Loredo, 34, rushed to the hospital to see her father.

San Diego Superior Court records show her father has a criminal record dating to 1983. That was a few years after he had immigrated to the United States from Cuba, when he was in his 20s. When he contracted COVID-19, Loredo had been in jail after a July arrest on charges of possessing and selling methamphetamine. He was also facing drug and DUI charges from a May 2019 arrest.

His daughter knows he made mistakes. He had been in and out of sober houses and jails for most of her life. For several years he was homeless. But she also has brighter memories: Her father’s love of music and playing the guitar. His upbeat personality.

When his daughter entered his hospital room, he looked thin and small — not the stocky built man she knew.

She said goodbye to him while he laid in a hospital bed, hooked up to a ventilator with two guards nearby — a reminder her father was still in custody. She was given 30 minutes with him.

“Seeing him like that, it did break my heart,” she said.

Her father died later that day, Nov. 21, shortly after 10 p.m.