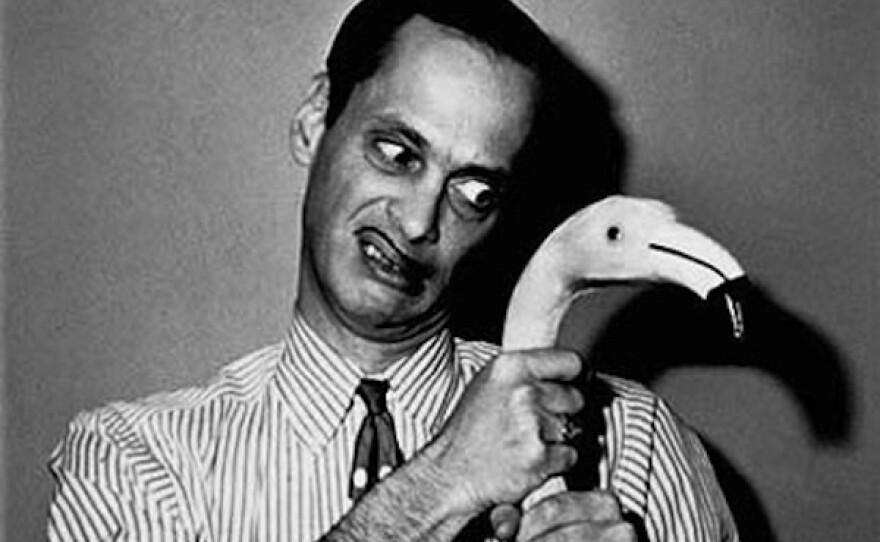

With "Pink Flamingos" playing tonight as part of FilmOut's monthly film series at Ultrastar Mission Valley Cinemas, I decided to dig back into the dusty interview vault to pull out some pearls of wisdom from the man known as the Sultan of Sleaze, the Prince of Puke, the Pope of Trash and the King (or possibly Queen) of Schlock — titles John Waters wears proudly. I interviewed Waters back in 1997 when he was re-releasing "Pink Flamingos."

Born in Baltimore in 1946, Waters grew up in a comfortable, conservative Catholic family. He knew from an early age that he wanted to make movies and began by making a pair of Super 8 films: "Hag in a Black Leather Jacket" (1964) and "Roman Candles" (1966). Then he borrowed money from his father to produce "Pink Flamingos," which was billed as an exercise in poor taste. While the content of "Pink Flamingos" — incest, murder, exhibitionism, singing anuses and eating dog crap — was a direct challenge to the standard Hollywood fare, Waters' approach to filmmaking drew on the Hollywood traditions he loved. He employed a straightforward storyline, emphasized entertainment over enlightenment and built a stable of stars that rivaled the old Hollywood studios — but with a twist. By embracing these Hollywood trappings, Waters signaled his eventual move into the industry where he proved highly successful with "Hairspray," "Cry-Baby" and "Serial Mom."

With "Pink Flamingos," Waters made an audacious bid for attention — and got it. But the film was more than just an attempt to shock. It was an all-out satiric assault on the middle-class values that Waters saw as oppressive and hypocritical. The film also lobbed a Molotov cocktail into the culture wars of the 1960s and early '70s. But what made Waters unique was the joyous quality of his work, the wicked delight he took in trashy obscenity. Waters' revelry at smashing establishment values and championing social misfits made his film irresistible to all but the most puritanical. Who can resist the gleeful and absolutely defiant 300-pound Divine, decked out in a sexy outfit and strutting down a Baltimore street to strains of "The Girl Can't Help It"? This was Waters and company giving the middle finger to conformity and conventional standards of beauty. Waters revealed a keen eye for social observation and genuine compassion for the outsider — skills he would hone to perfection in "Hairspray" in 1988.

Waters spoke to me from his beloved Baltimore and reflected on the film that brought him into the spotlight and gave trash cinema a good bad name.

What prompted this re-release?

John Waters: Well, the filth was rotting in the can, and it begged to be let out. I pitched this to Bob Shaye, who is the head of New Line Cinema — who I've known for a long, long time. "Pink Flamingos" was a big part of their history, and I knew the 25th anniversary was coming up and I had this footage that no one had ever seen before, so I pitched it to them as a good way to get a new video release and to get it back in the eye of the public. I didn't even realize at the time that all these other movies were going to be coming out with anniversary editions. So it turned out perfectly, it's sort of a spoof on "Star Wars" and all this good taste coming out.

Will you be restoring the footage like the murder of Cookie and the "Filthiest People in the World" song in pig Latin?

Waters: Yes, those are scenes that come back in the outtakes at the end.

So have you been holding on to all these scenes for 25 years?

Waters: Well, they've been in my attic. Actually, when they did the new version of the film, they did a new blow-up, they rescanned the film, they re-digitized the sound. I mean, it still looks terrible, it's "Pink Flamingos," but still, it will look as good as it will ever look.

Did you feel that a new generation needed to be exposed to "Pink Flamingos"?

Waters: Yes, I did. I think what I'm proud of is that the film still works. It hasn't mellowed while it's been sitting up there in my attic, the bile has not mellowed. It may be even ruder that it ever was, with all the political correctness going on now. Things have changed. I mean, 25 years ago it was shocking to have a plot where people sold babies to lesbian couples. But today, that's politically correct.

The thing that I admire is that after 25 years it still has the power to offend.

Waters: Well, everyone still talks about the final scene — (Divine eating dog crap) — being the most repellent. But I think the artificial insemination scene is probably the rudest scene in the movie. The taboos that are in "Pink Flamingos" are still taboos today. That's why I'm saying that I'm still proud of the film because it still does work on a level. I made that movie for audiences that thought they had seen everything and to laugh at the fact that they hadn't. I've even shown it when I've taught in prisons to a class of all murderers and they ran out of the room and told me I was insane.

Did you take that as a compliment?

Waters: Well, it shocked me at first, because I thought, Boy you're so touchy, considering these are like murderers, rapists and stuff. And they're telling me I'm crazy. It's strange, it shocked me, it made me laugh.

Do you still get complaints about the film?

Waters: Well, the film even got busted in Florida in a video shop about five years ago. What happens is families go out and they say, "Oh we loved 'Hairspray,' let's get another John Waters movie." Then they see something called "Pink Flamingos." That's why we very much wanted — and got — an NC-17 rating, because the last video release didn't have any rating. Some video shops don't know what it is and they just put it in the comedy section. Then some unsuspecting family goes home, rents the movie and then they call the police. Which I don't understand. Why don't they just turn it off if it's offensive? That's what I did when "Forrest Gump" started running. But no, they feel obligated to stop it like a disease.

I thought it was interesting that when I went to rent the film, it was no longer in Cult Movies or Midnight Movies. I was informed it was in the new section called Alternative Lifestyles.

Waters: Well, my favorite was when I used to see it in Foreign. I thought that was the best.

You described your film as obscene but in a joyous way.

Waters: Yeah, I think it is.

Do you think that's what offends people most?

Waters: No, I think that's what makes it popular. That's why people like it. I think joyously obscene can be wonderful and a celebration. Whereas real obscenity is nasty and makes you feel bad about yourself. I think "Pink Flamingos" makes you feel good about yourself. I do. I think it's a happy movie. It's a very Catholic movie, in some ways. It's very obvious that there's good and bad, and the good guys win and the bad ones are punished. It's a very moral movie.

Today, with all these shock jocks and confession talk shows, do you think you have to find another way to shock people?

Waters: The problem with that is that they are trying to shock people as their first goal. That was not my first goal with "Pink Flamingos." My first goal was to make you laugh at being shocked and there's a big, big difference in that. I've talked for years about good bad taste and bad bad taste. And here's where I think that comes into play: Bad bad taste is not very witty and is trying first to only be repellent. Whereas "Pink Flamingos" was taking being repellent and turning it into a style and was basically, in some kind of way, in good taste.

How did your parents react to "Pink Flamingos" when it came out?

Waters: My parents have still never seen the movie. But my father paid for it and I paid him back with interest. I think he was totally shocked to get his money back. I told them it was coming out again — and my father's 80 — and he said, "Oh no." I mean, they were horrified that they would have to live through that again. My mother joked and said, "Maybe we'll die first." She actually said that. My sister told me that they said maybe they should go see it this time and I said, "No, they really don't." I mean, why make them go see that movie? I think that's the thing that's changed the most, kids come up to me now and say, "My parents showed me 'Pink Flamingos.'" My generation's parents sure would have never done that.

But your parents were basically supportive of you?

Waters: Yes, always. Even though they were scared stiff of what I did — and horrified by it — and everything they believed in, these movies defied. But at the same time, I think they knew that at least I knew what I wanted to do and I was very passionate about it. Now I look back and realize how incredibly supportive they were. And I think whatever degree of mental health I have these days is because of them.

What was making the film like?

Waters: We shot sporadically, but I don't know why, because nobody worked, nobody had real jobs. We'd shoot maybe one day a week or something. When I'd get the money together to do it. I wrote it as I kind of went along, and the dialogue was always handwritten. We used what news teams used to use — mag-striped 16mm — and that's what it was shot with. That's why there's such long takes because you couldn't cut, because every time you'd make a cut, the sound had to overlap 24 frames. It was almost like filming a play. It was a very, very hard movie to make. But we were all young. All movies are hard to make, and when you're young, you can make them even harder.

How did you find Divine?

Waters: Divine lived down the street from my parents. I used to see him everyday, and he had different color hair every day as he was waiting for the bus, and my father would like tremble and rage as we passed by. I thought, God, I have to meet this person. So I met him through a girl that I knew who knew Divine because they used to gamble for pimple medicine when they played cards.

What was you're working relationship like?

Waters: I think it was a very good one. In the beginning, I don't think Divine believed that anything was going to happen with these movies. He didn't even quite get it in the beginning. In the very, very beginning Divine was like a real drag queen for about two seconds until I really got a hold of him. Because back then, other drag queens hated him immediately because they knew that we were making fun of drag queens because drag queens were really very square then. They all wanted to be like Miss America and wear mink coats and all that. And Divine obviously made fun of that image. I mean, here was someone who was fat and proud of it, which no drag queens were. Divine wasn't a drag queen and at the end, even in "Hairspray," he said no drag queen would ever have allowed himself to look like this. I mean, he was a character actor. And I think Divine had a lot of built-in rage. I mean, he was hassled in high school and I think he used that. Being Divine the character gave him an outlet for that and I think I had a lot of rage too, and I think the two of us channeled our rage into whatever character Divine was playing in the film.

The infamous final scene where Divine ate the dog crap, how did you come up with that?

Waters: I asked Divine, "Would you eat dog sh-t?" and he said, "Oh yeah." It was no big thing. You know that's the scariest thing about it, it really wasn't a big deal to us; it was pot humor, that's what it really was I think. It was the very last thing we did in the whole movie. I mean we followed the dog around, it was my friend Pat Moran's dog, she fed it for like three days and didn't let it out and it still wouldn't go and we kept following it around and following it around. Finally, we had to give it an enema with a hair dye applicator bottle and then it just dropped a little turd. Divine said, "Eat that little thing?" and I said, "Yes, we're losing the light, we've gotta do it." So he just did it. I remember looking through the viewfinder in my pitiful little 16 mm silent camera and just realizing that it was a surreal moment in our lives. The very first time I ever saw it with an audience, I knew that it really worked — beyond whatever I could imagine. But even then, I didn't think 25 years later I would still be talking about it. Divine eventually got weary from it — from talking about it — because he could never live it down. People were scared of him his entire life because he did that. It worked too well.

You're one of the few directors who is as well known as your films and your stars. People know you. How did you cultivate that?

Waters: Well, in the beginning we didn't have any money for advertising. We tried to think of ways to get people to see our movies, and it started out because I used to introduce my movies and that was, in a way, just some marketable way to get people to see our movies. I would come out and talk and then I would introduce Divine, who would come on stage pushing a shopping cart and throwing dead mackerels into the audience. That's how we used to travel. It was just kind of like some twisted showmanship.

You recently appeared on "The Simpsons" TV show, how did that come about?

Waters: They just called my agent and asked me and I said, "Sure." They asked Elizabeth Taylor, so I said, "Sure." If it's good enough for her, it's good enough for me. I played myself on "The Simpsons." Maybe I've become a cartoon character. I always wanted to be one. I always wanted to be a Disney villain when I was a child, so this is second best.

Does it bother you that the middle-class you criticize in your films are now embracing your films?

Waters: No, it's just another moment of irony in a life laden with irony. I realize I'm the establishment now. I mean, President Clinton maybe has seen one of my movies, there's a president now who possibly could have seen one of my movies. So no, I find it even more ironic and even funnier in a very, very strange way.