Two men set out in a car, one worries about his ailing son, the other seems intent on driving them north through the streets of Tehran, with the imprint of their crime on the throat of the man in the passenger seat.

Thus begins writer-director Mohammad Rasoulof’s taut political tale of an assassination gone wrong, a functionary who seeks to fix it, and the writers whom the Republic of Iran sees as so many inopportune flies to be dispatched or neutralized as soon as possible.

‘Manuscripts Don’t Burn”

Screens Sept. 3, at the Digital Gym on El Cajon Boulevard

'Manuscripts Don't Burn' goes well with 'The Closed Curtain' (Jafar Panahi), 'The Music Man (Sountouri)' (Dariush Mehrjui) and 'A Separation' (Asghar Farhadi)

Rasoulof has made quite a name for himself as the writer-director of wide-ranging films that take a clear-eyed look at Iranian society and critique the powers that be. Like fellow director Jafar Panahi, Rasoulof has been the object of censorship, this time a possible 20-year ban on filmmaking. None of his films can be shown in Iran, and Rasoulof, too prominent to disappear, too on point to be comfortable, currently is awaiting word on what the Iranian government plans to do about him.

Meanwhile, Rasoulof has made yet another film clandestinely. So clandestine was the filming, that the credits for the cast and crew roll past on blank screen after blank screen for their protection.

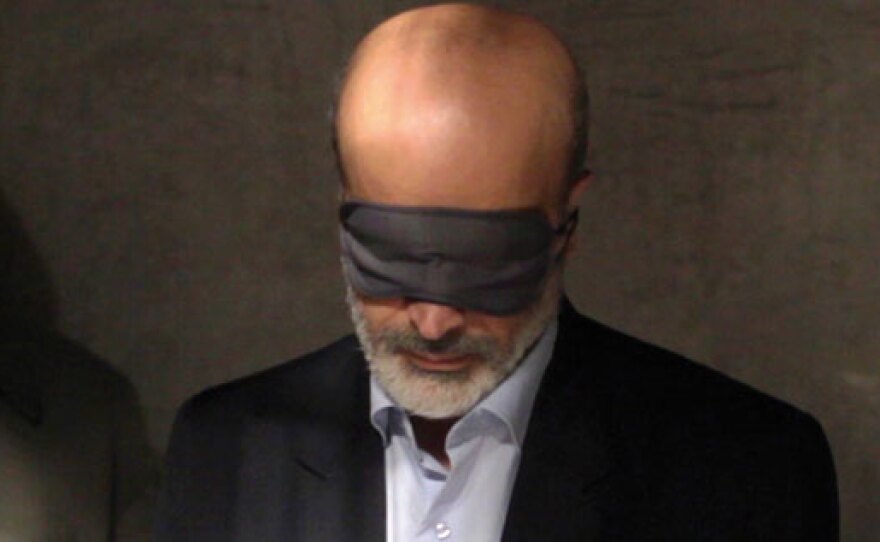

“Manuscripts Don’t Burn” turns on the cleanup of a botched assassination of a group of Iranian writers and intellectuals. Based on the real campaign of targeted assassinations — in addition to an infamous incident in 1995 when 21 writers going to a conference in Armenia were twice driven nearly off the road by their bus driver — the film takes a hard look at censorship and state control.

Rasoulof uses the incident as a jumping off point to follow two parallel threads: the writers who remember the incident and the government-paid assassins, Khosrow and Morteza. Linking the threads is a younger functionary, often referred to as “Haj Agha,” a once-fiery writer imprisoned for his work, turned apostate judge and jury. Embracing the party line, "Haj Agha" the posh and powerful newspaper editor, conflates it with his own, calculated need to survive.

It is the book of the incident that Haj Agha wants, the one that implicates him in the intellectual crimes of his fellow former writers, whom he calls “the Cultural Nato.”

And in an ironic twist of fate, it is the bus driver, now reluctant henchman, that he sends to close the circle.

One can see why the film was shot on simple DV cameras, discretely, quietly. “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” pulls away from typical current Iranian film with almost cold precision, its colors greyed out, its violence controlled, calculated, its salient moments left unseen and amplified in the imagination.

The title, aptly enough, is drawn from a famous phrase in "The Master and Margarita" by Soviet dissident Mikhail Bulgakov, a scathing satire of Soviet cultural practices.

You can feel the anger simmering, tightly wound beneath the surface of elegant interiors and imaginative edits that move scenes into nicely appointed homes and out into cold, thuggish scenery.

Rasoulof keeps his framing tight, often moving, to give both the hunter and the hunted an odd sense of symmetry. One handicapped writer’s wife frets over his drinking while the assassin Khosrow frets over his son’s need for hospitalization. On the other hand, there is no pussyfooting around the the role of the political, moral and cultural antagonist that is the younger functionary. No family, no small frailty makes him sympathetic. He's the bad guy Iranian film as been missing for awhile: icy, elegant, impersonal nastiness.

The director inserts a little humanity into the assassins, balancing them with the intellectual cantankerousness of the older writers, just enough so that the violence is made more chilling, the damning of the state more emphatic.

It’s a fascinating film, not for the faint of heart.