He left Guatemala as a teenager because he wanted to escape from the gangs that were recruiting him. He broke U.S. law by entering this country illegally and obtaining a false Social Security number in order to work.

Then he tried to do everything right: He got a job in construction, paid income taxes. He fell in love with an American woman, married her, and was an involved parent to their young daughter.

When Victorugo Rodriguez Tello, 27, was arrested in December by a team that included U.S. Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, he hoped his case would be resolved swiftly. He said he didn’t understand why they would bother with someone like him — eligible for a green card through marriage, with no criminal record that would disqualify him from permanent residence, living in the U.S. for more than a decade — when they had bigger fish to catch? Plus, he said, America struck him as a country with an immigration system shaped by logical rules and regulations, not intimidation.

Instead, Rodriguez, who lives in northeastern San Diego County, was shipped to a Calexico immigration detention center, a 150-mile drive away, where he stayed for nearly three months. When he asked for information about his arrest or incarceration, he got nothing, he said. His lawyer's bond requests were ignored or denied without an explanation. Until, one day in March, he was released on a bond of $3,000. He’d been in custody for 77 days.

“I suffered a lot because of what happened,” Rodriguez said in an interview at his mother-in-law’s home in Escondido. “The way I left my wife alone, especially because she was eight months pregnant. It really hurt a lot to leave (my wife and daughter) alone.”

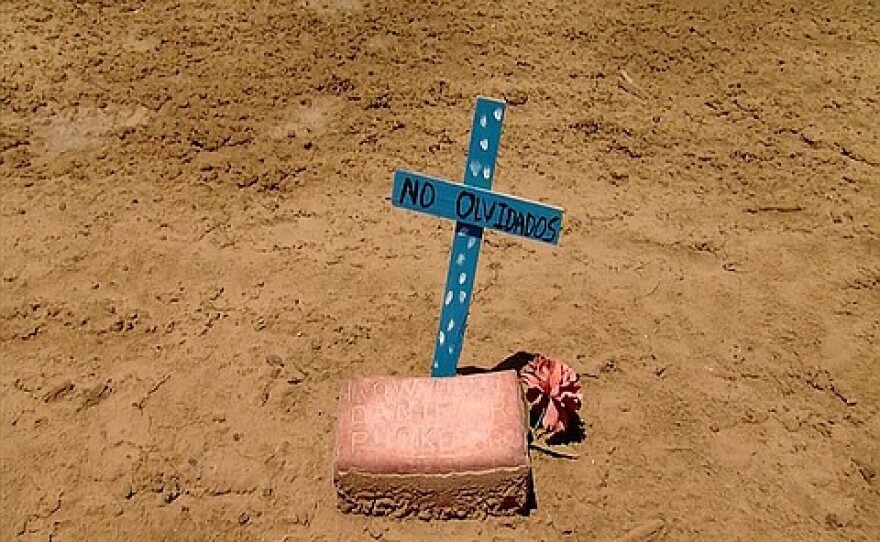

Rodriguez’s story is in some ways representative of a larger trend. He is one of hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and immigrants living illegally in the U.S. who are waiting for outcomes in the severely backlogged immigration court system. Some are detained in holding facilities; others live in their communities.

In one respect, however, Rodriguez’s case is exceptional. His three months in custody was longer than the vast majority of cases. It opens a window to the alternate legal universe of the immigration justice system, which some describe as capricious and opaque. Government agencies managing detainees, though, say the cases are not as simple as they might appear.

Costs of detention

At the time of his arrest, Rodriguez was recently married to his wife and they were sharing a two-bedroom cottage in Escondido with their daughter and extended family. (Among them was Rodriguez’s brother, who was also living in the U.S. illegally.) Rodriguez and five others present that night, including his wife, mother-in-law and his brother, were either detained for being in the country illegally or charged with harboring people here without documentation.

Rodriguez joined the massive number of immigration detainees, which has grown from around 257,000 in 2006 to around 441,000 in 2013, according to U.S. Department of Homeland Security reports.

The government said it acted correctly in arresting Rodriguez and said it tries to process every case — especially those of detained individuals — as quickly as possible. An immigration judge said that judges feel empathy for people whose futures depend on their rulings, but she added that limited funding translates to limited staffing and delays in processing cases.

Rodriguez’s lawyer, Matthew Holt, said Rodriguez’s release took unnecessarily long, at a cost to Rodriguez, his family and taxpayers. While incarcerated, Rodriguez lost his job, requiring his wife (who was close to her due date and not working) to go on welfare. He missed Christmas and the birth of his second daughter.

He could have been released sooner if hearings happened more frequently and if GPS ankle bracelets, not detention, were the norm for low-risk detainees, Holt said.

As for the taxpayer, the daily cost of keeping a person detained is around $159, so Rodriguez’s 77-day stay cost an estimated $12,200.

In fiscal 2014, the national budget for immigration detention was $2.04 billion, which covered beds for 31,800 inmates. That amount grew in fiscal 2016 budget, to $2.4 billion, covering 34,000 beds. According to DHS records, proposed spending on alternatives to detention (which includes electronic monitoring and supervision, which are both more affordable than detention) has also grown, from almost $94 million requested in fiscal 2015 to $122.5 million requested for fiscal 2016.

Finally, Holt said, Rodriguez's case points to underlying flaws in the immigration apprehension and detention system.

His case “exemplifies the arbitrary and capricious nature with which ICE may detain individuals at what amounts to a crippling social cost to our local communities and an exorbitant financial cost to taxpayers," he wrote in an email.

ICE, however, said it was justified given the broader investigation of people Rodriguez was living with.

“The enforcement action was part of a criminal investigation involving suspected alien smuggling activity. Two individuals were arrested on criminal charges for harboring illegal aliens and a number of counterfeit immigration documents were seized,” ICE spokeswoman Lauren Mack said in a statement. (The two individuals charged with harboring people were later released and no case was pursued.)

She continued, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is committed to operating a swift and efficient removal process for all individuals who contest their deportation from the United States, whether they are detained in ICE custody, released on bond or released on their own recognizance.” She said ICE coordinates with immigration courts “to expedite timely access to the legal system for all those in proceedings.”

Kathryn Mattingly, with the Department of Justice's Executive Office for Immigration Review, said courts make it a goal to process cases of people in detention quickly. The same goes for bond hearings, she said. Those are set on the “earliest possible” calendar date. When lawyers ask to move hearings sooner (as Holt did), those are addressed on a case-by-case basis, she wrote.

Rodriguez said he illegally entered the U.S. one time, more than a decade ago. He’s never been deported, and his FBI criminal record is clean, according to records shared by his attorney.

In recent weeks, the national debate over immigration policy has ignited over immigrants who have been deported and re-enter the U.S. multiple times, without criminal prosecution. One such man fatally shot a 32-year-old San Francisco woman earlier this month. He had been deported five times and had numerous felony convictions, mostly for drug offenses. Federal authorities have said the city didn’t cooperate with their request to keep the man in custody so he could be deported.

“Through the looking glass”

Whether Rodriguez’s arrest and detention were justified or his bond took longer than necessary to be approved, his story is a case study of justice in the immigration system.

Dana Marks is an immigration judge in California and president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, a group that lobbies for immigration court reform. Marks said that system is a “through the looking glass world” where principles and practices of justice and due process from the mainstream court system do not universally apply.

For example, representation in immigration court is not a constitutional right, so a lawyer is not provided by the government when someone can’t afford one. About 55 percent of the people whose cases were heard in fiscal 2014 — including Rodriguez’s — retained lawyers, according to federal statistics. That’s an increase from 40 percent since 2010. The rules of evidence also are different from mainstream courtrooms.

“Most members of the public don't have a clue about the realities of our world,” Marks said.

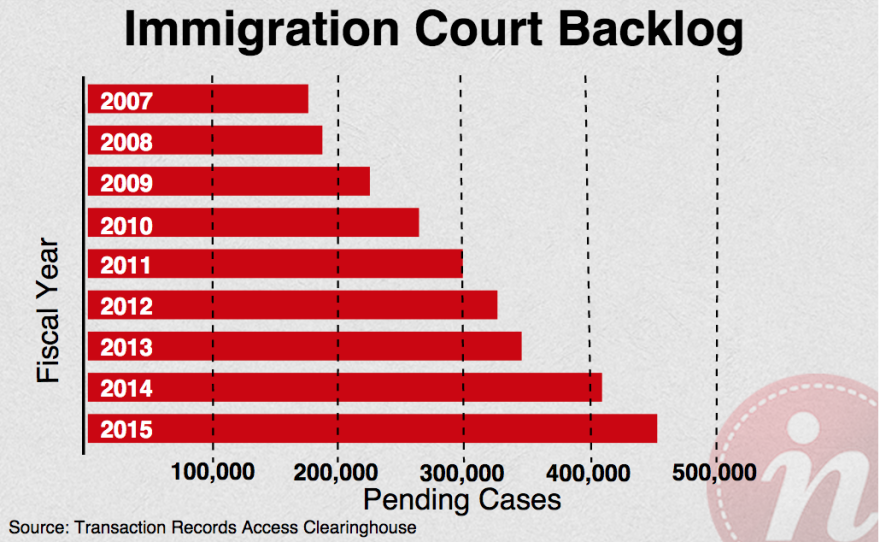

A “crippling” lack of personnel and funding makes immigration courts unable to function efficiently, she said. With more than 450,000 immigration court cases pending nationally as of June, Marks said some of the nation’s approximately 225 immigration judges are supposed to hear many thousands of cases per year. Try as they might, it’s impossible to move quickly while being diligent — let alone get through them all, she said. The backlog has grown every year since 2007.

Marks also said judges often want to give cases their time and attention but are forced by circumstances to rush. She said that if more funding went to pay for judges and if detainees felt the process was fair and thorough, then less money might be spent on appeals.

Nationwide, as of June, the backlog for all immigration court cases was around 451,000. In fiscal 2007, the backlog was around 175,000.

Since fiscal 2007, San Diego’s caseload peaked in fiscal 2012, while Imperial County’s has grown every year. The fiscal year begins Oct. 1, so the figures for this year are incomplete.

Mattingly, with the federal Executive Office for Immigration Review, said the number of cases nationally keeps increasing.

“Our caseload is the direct result of DHS immigration enforcement initiatives,” she said in an email. She added that a hiring freeze that lasted from early 2011 to early 2012 further cut the number of judges, because of attrition. Since the freeze was lifted, positions have begun to be filled again.

Written testimony in April from ICE Director Sarah Saldaña discusses an increase in judges and attorneys: “With the additional attorneys to support the expected increase in immigration judges, ICE anticipates to decrease the average length of stay for detainees by up to 14 percent, with an aim toward freeing up resources that otherwise will have to be spent on detention.”

Holt said other problems, in addition to the lack of judges, may have also contributed to delays in Rodriguez's release. For one, the procedures people go through in immigration court vary by location, which can lead to longer stays based simply on where a person is detained.

In some jurisdictions, detainees automatically get hearings with a judge after a week or two. In San Diego’s immigration court, there is no such rule. “A person could be detained for weeks or months before they get a hearing, because it's not automatic,” Holt said.

Even though the immigration courts are federal, procedures differ locally. “They're all different offices,” Holt said. “Every judge runs their court differently. Every office of chief counsel runs its office differently. Every enforcement and removal office with Homeland Security runs its office differently.”

Taken together, these factors create a different approach to justice for the country’s immigrants. In the mainstream criminal court system, even a murderer gets a court date, Holt said.

When someone is charged with a crime, “You don’t just stay detained for months without a hearing. I mean, that's what they do where? Guantanamo? Somewhere other than here,” he said.

“We have so much respect for our system, and our system really is a system that's looked at from the whole world as an example. And we're failing. We're not only failing ourselves, but we're failing as an example to the entire world.”

Rodriguez is shy about his English, even though he's been speaking it since learning it in school in Guatemala. So in Spanish, he conceded he didn't initially follow the rules in entering the United States. But his lawyer said Rodriguez was like many immigrants — he imagined that getting a green card through marriage would be as easy as snapping his fingers. He earned less than $30,000 in 2014, according to an earnings statement. Green card application fees are more than $1,000, and obtaining permanent residence is not something that happens overnight.

Rodriguez said the experience in detention was eye opening. One night he was eating pork chops with his wife, and the next he was in jail.

“My impression of the immigration system used to be better,” he said. “Now I think it’s a system with no logic, no rules, and that they can do whatever they want.”

He'll continue to familiarize himself with the system over the coming years. He's waiting on a work permit, which should come soon, his lawyer said, and he and his wife have paperwork to file as they prepare his case for legal residence. The government has given him permission to stay in the U.S. until his next court date, which is scheduled for 2017.

Correction: This story has been updated to remove a statement about the typical immigration detainee.