Maureen Cavanaugh (Host): It's a disease that cuts through class, race and cultures. It can strain the most intimate relationships, making normal work and daily routines impossible. And it can even make life itself seem not worth living. The disease is depression and it's the subject of a new documentary airing on KPBS and other public television stations this month.

The program introduces us to people from all walks of life who are struggling with depression. It also explores the treatment options from drugs to therapy and support groups.

Guests

Susan Schutz, Filmmaker, The Misunderstood Epidemic: Depression, author Depression and Back: A Poetic Journey Through Depression and Recovery

Gina Stevens, Founder of the Suicide Prevention Walk

David Peters, Marriage and Family Therapist

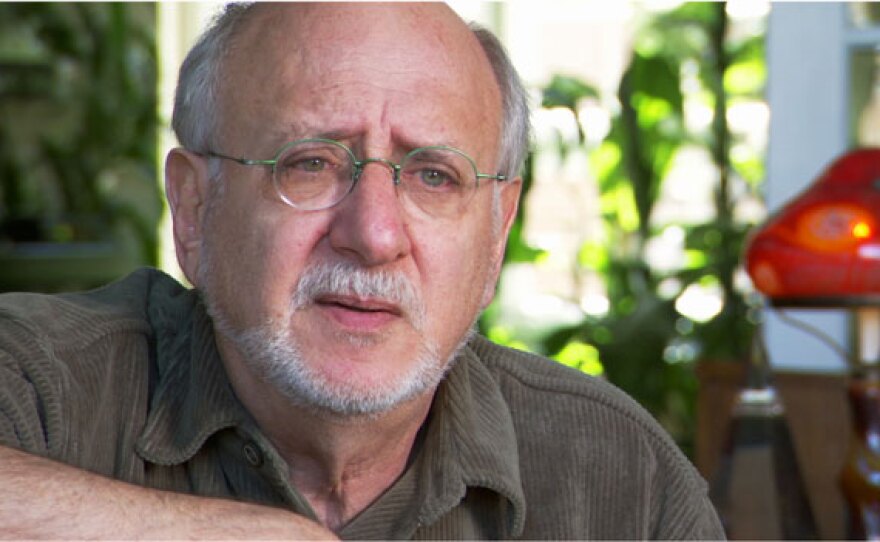

Dr. James S. Gordon is founder and director of the Center for Mind Body Medicine in Washington, DC. He is also a clinical professor in the department of psychiatry and family medicine at the Georgetown University School of Medicine. Dr. Gordon is the author or editor of twelve books including his most recent one, UNSTUCK. He also served as the chairman of the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy.

Public Info

"The Misunderstood Epidemic: Depression" airs on KPBS Television on Tuesday, May 11 at 9 p.m.

MAUREEN CAVANAUGH (Host): I'm Maureen Cavanaugh, and you're listening to These Days on KPBS. It's a disease that cuts through class, race and cultures. It can strain the most intimate relationships, making normal work and daily routines impossible. And it can even make life itself seem not worth living. The disease is depression and it's the subject of a new documentary airing on KPBS and other public television stations this month. The program introduces us to people from all walks of life who are struggling with depression. It also explores the treatment options from drugs to therapy and support groups. This morning we’ll be speaking with the creator of the documentary and we will be taking your calls. I’d like to welcome my guests. Susan Polis Schutz is producer and director of the film “The Misunderstood Epidemic: Depression,” and she’s author of “Depression and Back: A Poetic Journey Through Depression and Recovery.” Susan, welcome to These Days.

SUSAN POLIS SCHUTZ (Producer/Author/Director): Thank you very much.

CAVANAUGH: Gina Stevens is founder of the Suicide Prevention Walk here in San Diego, and she appears in the documentary. Gina, welcome.

GINA STEVENS (Founder, Suicide Prevention Walk): Thank you very much.

CAVANAUGH: And we’d like to invite our audience to join the conversation. Do you suffer from depression? Do you have a family member who struggles with it? Tell us your story and how you’re coping. We’re taking your questions and your comments. Our number is 1-888-895-5727. Susan, we’ve all heard about or even experienced depression in our lives and in the lives of family members and friends for years, so why do you think it is, as you call it in your documentary, still misunderstood?

SCHUTZ: Well, there, excuse me, there’s a huge stigma attached to this illness unlike other illnesses, and people don’t understand it. They think you can just get a grip on your life and overcome it. And that’s not true; it’s an illness.

CAVANAUGH: Why did you decide to do a documentary on depression?

SCHUTZ: Well, I’ve always had a very uplifting and positive attitude but about four and a half years ago I plunged into a horrible clinical depression, which I didn’t even know what it was. I was in bed for three months. And when I finally got out and I went to a psychologist and I got on medications, I learned a lot about depression and I wrote a book, “Depression and Back” about my journey with depression. And then I wanted to help other people understand what depression is and give them hope for happiness, so I decided to do the movie and interview victims and their families of depression.

CAVANAUGH: I want to ask you a little bit more about your own personal experience because that’s very interesting to me. You were depressed…

SCHUTZ: Yes.

CAVANAUGH: …but you say you really didn’t even know what was going on.

SCHUTZ: I had no idea. I thought I was sick physically. I was in bed. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t talk. I was numb. And I just thought there was something physically wrong with me. I got myself out of bed a couple of times to go to regular doctors and there was nothing wrong with me. After about three months, I actually spoke to a couple of friends who kept calling me and I didn’t return the calls and they said – Actually, my best friend is a psychologist and she said it sounds like you’re depressed, you’d better go to a psychologist or therapist, and she recommended somebody. I told her what kind of person that maybe I could go to. I knew nothing about that world. I knew nothing about therapists, nothing about medication. And when I got myself to go to the therapist, she said I was absolutely clinically depressed.

CAVANAUGH: And what kind of symptoms did you experience…

SCHUTZ: Oh…

CAVANAUGH: …that you mistook for physical illness?

SCHUTZ: Well, I was so lethargic and so tired, I was exhausted. I had no pain, no physical pain, but I was frightened, I was miserable. But I think the most prevalent feeling I had was like a numbness, just a total numbness of my whole mind and body.

CAVANAUGH: Now was it difficult, therefore, to find people to participate in the documentary that you decided to make?

SCHUTZ: You know, the people were so wonderful. When you start to feel a little bit better, you just want to reach out to other people that feel that horrible. So when I found these people—and I found most of them at a support group—and they all were wonderful. They all, like Gina, wanted to help other people understand what it’s like. And so it was not – There were a few people that didn’t want to, quote, come out and say they were depressed but other than that, everybody was absolutely willing and wanted to help alleviate the stigma of depression.

CAVANAUGH: I’m speaking with Susan Polis Schutz. She is the producer and director of the new film that is airing on KPBS, "The Misunderstood Epidemic: Depression." We’re taking your calls at 1-888-895-5727. Before we start taking calls, I do want to hear from Gina Stevens. As I say, she’s founder of the Suicide Prevention Walk here in San Diego but you’re also, Gina, in the film, in this documentary as well. How did you get involved in the film?

STEVENS: Well, I happened to go to one of the support groups, the bipolar and depression support groups, and basically I met Susan there and she approached me and said would I be interested in doing something like this and I said absolutely. I was very interested in it right off. I didn’t have any reservations or any problems with doing it.

CAVANAUGH: And yet, as Susan says, there is a stigma attached to being depressed and having depression. Why did you leap at this opportunity so quickly? Did the idea of going public with struggling with depression make you think twice?

STEVENS: No, in my case probably it didn’t. I felt like I had lived so many years with struggling with depression. I’ve had it for over 20 years now, and I just thought that if I could help anybody else – I’m from a medical background. I’m in the medical profession myself. And so not only did I see people with depression but then knowing my own story and what I had, I thought if I can help anybody to get to somebody sooner or to get it diagnosed, get treatment with all the different options there are, then that would make me feel so good and would be so rewarding for me to not have somebody go through the number of years that – or the struggles that I’ve gone through personally.

CAVANAUGH: Now, Gina, your mother is in this documentary as well.

STEVENS: Correct.

CAVANAUGH: And she talks very movingly about all the years that basically she just didn’t understand your disease. She just, you know, wanted you to use your Irish gumption…

STEVENS: Umm-hmm.

CAVANAUGH: …and just pull yourself up by your bootstraps. And do you – do people who suffer from depression hear that a lot from other people? Come on, just get over it.

STEVENS: Absolutely. I’ve had many friends, many people, and, again, including my mom—and I love my mom dearly—but say, oh, you’re just having a bad day, you just need to put on your clothes, get out of those pajamas, go out and walk around in the sun, go to a movie, listen to some music, I mean, it was something like just, you know, snap out of it. That’s kind of the attitude. You know, you’re just having a blue time or a bad time right now and if you just – if you just meet with some friends, if you just go to a movie, if you just get outside, if you just take your pajamas off, if you can just brush your hair and, you know, brush your teeth, then everything is going to be fine. And it’s not because you don’t – you’re not capable of even doing the smallest of things. So the thoughts of even walking outside, the thoughts of taking off your pajamas and putting on clothes is monumental.

CAVANAUGH: Let’s take a call. We are taking your calls at 1-888-895-57 – I’m sorry. 1-888-895-5727, that’s 1-888-895-KPBS. We are talking about depression, most specifically the new documentary, "The Misunderstood Epidemic." Let’s hear from Lalo in Mission Valley. Good morning, and welcome to These Days.

LALO (Caller, Mission Valley): Good morning. I have a son who struggles with depression and even though I’m educated, you know, and I have some mental health background, it really is extremely hard for parents to deal with it without anger, without shame, shaming my son, and I’m very excited about the film. I think we need more education. What is one or two more things that parents could do to really help a child struggling with this disorder without making things worse?

SCHUTZ: That’s a really good question. You sound like you’ve done the first thing, is educate yourself about depression and take it very seriously that he’s depressed and probably go to a doctor as soon as you can.

CAVANAUGH: And, Gina, what advice would you offer? What are some of the other things that parents might be able to do if they have children who suffer from depression?

STEVENS: Well, I think the first thing is recognizing it and not just diminishing it but recognizing and saying to that child, I understand that you have an illness, I understand this is not just something that is going to go away in an hour or day or just with the, you know, a movie or I’ll take you out to eat or get your something – get you something you wanted. But recognizing that to the child and saying I know you have a problem and we’re going to get help together. I think that’s such a huge thing and so much support that it’s not just, so to speak, in their head.

SCHUTZ: Umm-hmm.

CAVANAUGH: Susan, how did you identify the other people besides Gina who are in this film? There is certainly one person that everyone’s going to recognize, Peter Yarrow from Peter, Paul & Mary. How did you find out about his struggles with depression?

SCHUTZ: Yes, most of the people I found, I went to 300 support group meetings and most of the people I found that way. Peter Yarrow’s a very good friend of mine, and he knew I was depressed and he opened up and told me he had been depressed and went through his story and so I asked him if he would be in the movie because he has – he represents somebody that has everything going for him, and I wanted to show that viewpoint where you don’t have to be down and out or have a…

STEVENS: Umm-hmm.

SCHUTZ: …an exact cause to trigger the depression, you can just be depressed. So he shows that.

CAVANAUGH: Indeed, you have a wide range of people from every walk of life. Tell us a little bit about the other people who are featured in your documentary.

SCHUTZ: Well, you know, you talk – you were talking about stigma and there’s a Japanese woman who had to have her face blacked out and her voice distorted because she was so afraid her boss might find out that she was depressed because on her application it asks if you have ever been depressed or if you’re on medication and she lied, of course, because she knew she wouldn’t be hired if she had put that down, so that’s one person. We have a wonderful couple whose daughter died and had suffered from depression for a very long time, and they’re very open and honest about what that does to a family. Let’s see, we have a Muslim woman who suffered from depression and her religion sort of got her through. Who else, Gina, do we have?

STEVENS: The gentleman, Gordon.

SCHUTZ: Gordon, yes, from…

STEVENS: Yes.

SCHUTZ: ...San Diego. He’s the only one that I found that actually got better without medication and I really didn’t want to take such a pro-active, pushing medication, and I looked very hard to find somebody that got better without medication and he shows that viewpoint.

CAVANAUGH: We’re going to be hearing a little bit more about the medication or not medication…

SCHUTZ: Yeah.

CAVANAUGH: …in the second half of our program today. Let me go to the phones because there are a lot of people who want to join our conversation.

SCHUTZ: Okay.

CAVANAUGH: Melissa is calling from Carmel Valley. Good morning, Melissa, and welcome to These Days.

MELISSA (Caller, Carmel Valley): Hi. Thank you. I – My comment was my mother suffers from fibromyalgia and she actually has been misdiagnosed many times. It’s frustrating for her because she’s kind of on the other side of the coin, if you will. Many times doctors have said, I’m sorry, you’re just depressed, here, take this antidepressant, you’ll feel better, when she feels like, okay, if I had cancer and I was depressed because of it, the doctor wouldn’t give me an antidepressant and say this’ll make you feel better.

CAVANAUGH: I understand.

MELISSA: So, yeah.

CAVANAUGH: Yes, thank you. Go ahead. I’m sorry.

MELISSA: So I guess my question is, you know, misunderstood is so true and it goes both ways, over, you know, overexaggerated maybe and underestimated, I guess.

CAVANAUGH: Melissa, thank you so much for the call, and you can see that there are many other conditions and diseases that are misdiagnosed. But I want to pick on one thing that Melissa said in that. The doctor, Gina, said, is you’re just depressed.

STEVENS: Umm-hmm.

CAVANAUGH: And that must really rankle you who struggled with this illness for so many years.

STEVENS: It does because, again, I think there – it’s kind of a maybe a way of diminishing it or saying that, well, you’re just depressed, you know, let me give you some medications. And it’s so much more than that. I think that the medications are part of it but also going to therapy is another extremely important part of the puzzle.

CAVANAUGH: You talk in the documentary, Gina, about how you’ve been treating your depression. Tell us a little bit about that.

STEVENS: My – What I’ve had with depression that’s worked for me and this doesn’t necessarily – is not going to apply to everybody. But personally, for me, I’ve had a lot of therapy and it’s been one-on-one therapy, group therapy, to get through some of my issues of childhood and things that actually did cause my depression in my particular case, and then medication has been something that I’ve also taken but I’ve also been through the gamut of many, many medications. I’ve taken probably at least 18 different medications and either for some reason they didn’t work or they did work and then I – they stopped working and so I’ve been through that with it. And I think talking about it, getting involved with other people that are struggling with the same disease, for me, breaking the stigma, getting out there and, you know, not being embarrassed or shamed by it and saying, yes, I do have clinical depression but there’s another side of this, there is hope.

CAVANAUGH: Susan, you know, one of the most startling things for me watching your documentary was to see that on the one hand drugs and pharmaceuticals offer so much hope to people but they also have to be managed so strictly and sometimes they just stop working.

SCHUTZ: Umm-hmm. They stop working and they also cause incredible side effects, weight gain, lack of creativity, lack of emotions, fogginess. So as everybody pointed out, you have to have a balance, and that’s why you need a psychiatrist to work with very closely. I also have been on many medications to find the right balance.

CAVANAUGH: Let’s take another call. Colleen is calling from San Diego. Good morning, Colleen. Welcome to These Days.

COLLEEN (Caller, Clairemont): Good morning. I’m actually calling from Clairemont but…

CAVANAUGH: Yes, but close enough.

COLLEEN: Okay. I just – I know. I just wanted to call and say that I’ve been suffering from depression for a long time. I’m 43 now and after I graduated from college, I found that I started suffering the symptoms of depression so I tried to get myself back on track by myself for about 10 years until I really couldn’t take it anymore and then I got myself on medication and I’ve been seeing a therapist for like seven years and stuff. And I thought, oh, great, finally the treatment is working, you know, I don’t feel the symptoms of depression anymore and after ten years of this, all of a sudden, bam, in the last year or so I just went right down the tube again, right to where I started over again. And it was so difficult and I was so surprised that these kinds of things happen. I thought that once you get treatment then it wouldn’t come back again but so I’m now back to my psychiatrist trying out different meds and things. But, boy, what a hard trip it is.

CAVANAUGH: Colleen, thank you for that. Gina, you’ve been through that.

STEVENS: Absolutely, I’ve been through that many, many times. Just when I thought that I was through this bout and I’ve conquered it and that’s it, that’s exactly what would happen. I would go back in and back under, as I say, and Susan describes the numbness that you feel and I felt the numbness but I also felt very much a heaviness like I was just being squashed to the ground. And I described it as a feeling of being dead. That’s, you know, I’d see this – the doctor or the therapist say, how do you feel? I feel dead. And that’s – you know, I think that is one of the hardest things is when you do think that you’ve conquered this disease—and it is a disease—then all of a sudden something triggers it or something may not trigger it, you may not even know what it is and you start going down again. And unless you learn to recognize those symptoms, which is absolutely, I think, one of the keys is writing down what are your triggers and when you are starting to go into a depressive episode where, you know, it’s heightened, that you recognize what that is so that you can try to, you know, intercede and help before it gets to the point where you are nonfunctioning or have to enter a hospital, which I have done.

CAVANAUGH: Are those triggers different for everyone?

STEVENS: I would say that they are. I’d say that different people have different triggers as to what it is but it’s important to know what those are and to actually write them down because it sometimes is so insidious that you may not see that you’re actually going down until all of a sudden you hit rock bottom and then you can’t get out of bed and you can’t go to work and you can’t brush your teeth or your hair or fix food or do anything. You can’t leave the house.

CAVANAUGH: Susan, let me ask you, how are the other people who were in your documentary, how are they doing today?

SCHUTZ: Yeah, I’m in contact with all of them. We have a nine-year-old boy that’s in it and he’s not doing too well right now but everybody else in the movie is actually doing very well. They’ve all seen – because when I interviewed – even when I interviewed Gina the first time she was just really depressed and crying a lot and then I think I interviewed her again maybe six to eight months after that when she found the right medication and she was a new person. So….

STEVENS: Umm-hmm.

SCHUTZ: …everybody has really progressed.

CAVANAUGH: That’s – that’s good to hear.

SCHUTZ: Yes.

CAVANAUGH: Let’s speak with Raj. He’s calling from San Diego. Good morning, Raj. Welcome to These Days.

RAJ (Caller, San Diego): Hi. Thank you. Thank you for taking my call. My question is about my son who has an autoimmune skin disorder. And he’s a teenager who performs extremely well in school. However, when he had this, he couldn’t go to school because it affected his whole skin and body, his appearance. His colleagues, students, various, and teachers, some of them, felt that he was faking it. So my question is what is done to help teenagers both in the school system as it applies to the teachers to help them cope with this…

CAVANAUGH: Thank you.

RAJ: …to make people understand that this is really not somebody faking it. I mean, he doesn’t want to fake it. He doesn’t like it.

CAVANAUGH: Right.

RAJ: But he has it.

CAVANAUGH: Thank you, Raj. You know, there are a lot – there’s a lot in what Raj asked us and in the second half of this show, we’re going to be talking about the difference between having a bout of depression and actually being clinically depressed. But I also want to ask you part of Raj’s question, Susan, and that is what about younger people? Is it harder for younger people who are suffering from depression to be taken seriously because I know you have a teenage girl in your documentary who said – who really was suffering and her parents just didn’t realize it.

SCHUTZ: And, you know, that’s very common. That teenager was going to commit suicide – tried to commit suicide and her parents still didn’t take it seriously. I think parents tend to think their kids are just having a bad day…

STEVENS: Umm-hmm.

SCHUTZ: …and they don’t know what to do about it. They don’t know much about depression. So, again, my advice is to really be – to really take your child’s behavior seriously and get help.

CAVANAUGH: And what about schools? Do schools do enough to screen kids for depression?

SCHUTZ: You know, they don’t really screen them and this nine – the mother of the nine-year-old boy had to go meet with his teachers many times because he acts out when he’s depressed and they didn’t understand it, they just thought he was a bad kid, which he’s a wonderful kid. So it’s very important for the parents, once they understand that their child is depressed, to go speak to the teachers.

STEVENS: The other thing, too, with the children, I think, is that the tendency is to think that they’re just going through a, quote, stage.

SCHUTZ: Yeah.

STEVENS: That they’re – it’s not depression, it’s not a disease but it’s just a stage. You know, you have the different stages when you, you know, that you go through and especially that pre-teen, teen years when, you know, your hormones are changing, things are changing, school is changing, and the thought is that, oh, they’re just rebelling. You know, they’re just – they’re rebelling, they’re trying to make my life difficult and, you know, they’ll pass through this and if I – or if I just ignore it and I don’t bring it up, which I think only propagates the problem.

CAVANAUGH: Now I know, Gina and Susan, you have to leave us at the bottom of the hour. I’m going to ask you just quickly, Gina, I know that there’s a very important date coming up this month. You were – have organized Survivors of Suicide Loss Day and that’s happening on May 22nd, and that comes out of an event that happened in your own life.

STEVENS: Yes. Actually, I haven’t organized that. The walk is what I organize but we do have the San Diego Survivors of Suicide Loss which is put on through Survivors of Suicide Loss and that is an incredible support group for people that have lost somebody to suicide. It’s actually – if you go to www.sosl.org, this day is going to be May 22nd, as you said, Saturday, from ten to two at Vista Grande Community Church and the title of it is “After Loss, Finding a New Normal.” And one of the things that they’re going to have panels of survivors and professionals followed by a question and answer period but also the other important thing is there’ll be breakout groups, small groups, that you can – that are formed by the loss of somebody that you suffered, whether it be a spouse, a sibling, a parent, a child, and that gives you really a chance to connect with someone who understands what that loss is all about.

CAVANAUGH: And for anyone who didn’t get a chance to jot that down, you can find links to that, the information about Survivors of Suicide Loss Day on our website, KPBS.org. And before you have to go, Susan, I’m just wondering what you hope people are going to take away from this documentary?

SCHUTZ: I’d like people to understand what depression is, how it affects the victims, how it affects the families, and I also want to give them hope, I think, for happiness and that they can possibly or most likely get better.

CAVANAUGH: Susan Polis Schutz, thank you so much.

SCHUTZ: Thank you very much.

CAVANAUGH: Gina Stevens, thank you for being here. Yes, go ahead.

STEVENS: Yes, I just wanted to also bring up the walk, which is the walk is actually what I founded…

CAVANAUGH: Yes.

STEVENS: …the Survivors for Suicide Walk and that will be on Sunday, November 14th at Balboa Park. Registration is at 6:30 and the walk starts at 8:00 and that walk is very important, not just for people that are survivors but survivors in many terms, not only survivors of suicide but also people that have lost someone to suicide and it’s a chance to connect – that Carol LeBeau is the honorary chair and keynote speaker. And there will be resources there from all around the county on just about everything you could possibly imagine.

CAVANAUGH: Gina, thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

STEVENS: Thank you.

CAVANAUGH: And I do want to let – if you’re not overloaded with information, I wanted to let everyone know that "The Misunderstood Epidemic: Depression," that documentary, will re-air on KPBS tomorrow night at nine. And stay with us. We’re going to continue to talk about depression, its effects on people and the people who love them as we continue on These Days here on KPBS.

CAVANAUGH: I'm Maureen Cavanaugh, and you're listening to These Days on KPBS. We continue our discussion about depression, its effect on people’s lives and the treatments available. I’d like to welcome my guests for the rest of the hour. David A. Peters is a Marriage and Family therapist in San Diego. And, David, welcome back.

DAVID PETERS (Marriage and Family Therapist): Good to be back, Maureen.

CAVANAUGH: Dr. James Gordon is founder and director of the Center for Mind Body Medicine. He’s also a clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Family Medicine at the Georgetown University. And Dr. Gordon is the author of the book, “Unstuck: Your Guide to the Seven Stage Journey out of Depression.” A television special based on the book “Unstuck” has aired on KPBS-TV. And, Dr. Gordon, welcome to These Days.

DR. JAMES GORDON (Founder/Director, Center for Mind Body Medicine): Thank you very much. It’s nice to be here.

CAVANAUGH: We are continuing to take your calls, listener calls about depression, your questions and comments. Our number is 1-888-895-5727. Let me start with you, if I may, David. You know, I think there’s a lot of confusion about what the difference is between going through a bout of depression, feeling sad, blue, not really happy, it’s Monday, something going wrong in your life, and having clinical depression. What is the difference?

PETERS: Yeah, well, we have a misnomer in our culture. People will say, oh, I was really depressed over the weekend when they were really sad. And sometimes sadness, even deep, long sadness is very appropriate if someone in your life has died or if you’ve lost your job or if some other tragedy’s gone on. And sometimes we just have long periods in our life where we’re not enjoying ourselves and sadness is predominant. But depression, clinical depression, is actually a change in brain functioning, which is accompanied by a slowness of your thought process, a lowering of your energy and sometimes there’s sleeplessness or sometimes there’s excessive sleep. Sometimes you lose your appetite altogether. And so it’s much more risky than a regular sadness and quite debilitating if not treated because it’s actually a change in brain function and a change in body functioning and it can be progressive if not treated. And it can really change things for your family, you can lose your job and, of course, for some people lead to suicide.

CAVANAUGH: I wonder, David, what do we know about how sadness can turn into depression? Is there a crossover there?

PETERS: It’s a complicated issue there. Some people are just resistant to depression. They may be very sad for a long period of time but not drop into a clinical depression whereas other people genetically, biologically, they’re vulnerable to a depression. As your guest Susan Schutz said, she didn’t even know she had depression. Her body shifted into it and suddenly she had this incredible exhaustion. And so for some people who are biologically vulnerable to depression, yeah, being incredibly sad, having some tragedies in your life, or particularly the feeling of hopelessness and helplessness. When we’re in a continuously helpless situation then we’re vulnerable to being – someone who’s vulnerable to depression would be vulnerable to falling into it then and then they’d experience from sadness going to that slowness of mental processing. You can literally feel like a cloudiness in your brain. I ask my clients, does it feel like it’s cloudy in your brain? Can you – is it hard to think? They say, yeah, that’s it. And I say, does it ever feel like you’re trying to march through a river of molasses and they say, yeah, it’s that inability to just move yourself. And so, yeah, sadness for a lot of people will just remain sadness but for a minority of the population it puts them at risk for clinical depression.

CAVANAUGH: Dr. James Gordon, you document that you, indeed, suffered from a bout of clinical depression many years ago. How would you describe the symptoms of your depression?

DR. GORDON: Well, I think David has described many of them pretty well. I felt pretty inert. I didn’t really want to do much of anything. I felt discouraged and guilty about the way I’d acted in the past and doubted that life could change much for the better in the future. And I’m somebody who is, you know, generally very, very active and I felt kind of lethargic most of the time and I was not able to do or take any pleasure in the things that I’d done and taken pleasure in before. And those feelings of hopelessness, you know, is this ever going to change, and helplessness, you know, is there anything that I can do to make it better? Those were very prominent for me. So it’s – you know, I’m very familiar with it from the inside as well as from working with thousands of people over the last 40 years or so.

CAVANAUGH: How did you, as a medical professional, how did you get yourself out of this depression?

DR. GORDON: Well, I was a medical student at the time. And I write about this in “Unstuck,” and I – you know, I’d had a – I mean, I think that the – first of all, the things that I recognized, the causes, that this was a human experience, first and foremost, even though it certainly felt like a – at times like a physical illness. That is, that I had – my girlfriend and I had broken up and I was unsure and which was devastating to me even though I’d, to be sure, had done – wasn’t significantly responsible for the breakup. And also, I was unsure about, you know, who I was and who I – and especially who I was going to be. So I was in this state of, you know, where do I go and how can I be the kind of doctor that I – and the kind of person that I hoped I could be. And what was most helpful for me right from the get-go – There are many more things that I know and work with and that I’ve learned over the years but the most important thing for me in – at that time, in that position, was to be able to reach out to another human being who was interested in me, who understood me, who had been there himself, and who could really serve as a guide and also, in many ways, an example. He was a psychiatrist. He was a young psychiatrist at the time, who was doing work that was deeply meaningful. He happened to be working with kids who were integrating the schools in Louisiana…

CAVANAUGH: Umm-hmm.

DR. GORDON: …in the 1960s, ‘50s and ‘60s. And he was – I think, you know, so he listened and he was there for me and he, you know, he didn’t think I was crazy and he didn’t think I should just shape up. He had a sense that this was part of my life, that it wasn’t some kind of weird thing that had come on me the way, you know, a bacterial pneumonia comes on people.

CAVANAUGH: Right.

DR. GORDON: This was a part of being a human being and that there were human solutions to it and that he, as someone who’d been there, could help to guide me toward those solutions.

CAVANAUGH: I’m speaking with Dr. James Gordon and David Peters. They’re my guests during this half of our program, still speaking about depression. Our number is 1-888-895-5727 or if you’d like to, post your comment or question online at KPBS.org/thesedays. Let’s take a call right now and a lot of people want to get involved in this discussion. Laura is calling us from Oceanside. Good morning, Laura, and welcome to These Days.

LAURA (Caller, Oceanside): Good morning.

CAVANAUGH: Yes.

LAURA: My son is 23 years old. He is currently not living at home. He was not getting a job, laying around, so we, unfortunately, had to kick him out. So he’s living out of his car. He’s contacted me saying he’s really depressed, he’s paranoid. Unfortunately, he has no insurance, no income, and he – and I’m really looking for a place to help him.

CAVANAUGH: Thank you for the call, Laura. What advice might you give her, David?

PETERS: Well, I do run into clients now and then who are in this difficult situation. If he’s experiencing paranoia, he’s definitely going to need some help. You can take someone to County Mental Health, and you can find them in the phone book. And at County Mental Health, on public funds, they can get him on medications if necessary. At least they can get him evaluated. In severe circumstances, they can actually hospitalize someone on – at the public’s expense and it’s a good last resort. On the other hand, there are also, for more minor cases, places around town who, with charity funding, can provide low-cost therapy. And to find those, you’d want to kind of, let’s see, get into the help line. If you dial 2-1-1 on your telephone, someone will answer who’s got access to a very good database of all the publicly funded social and psychological services in the county available, and they can give you some leads. Places like the YMCA, Jewish Family Services, places like that, provide low-cost therapy and sometimes no-cost. But if he’s experiencing paranoia, it’s a very negative indicator, if it’s accurate. And sometimes people are rightly fearful because they’re living in their car but if it’s paranoia that could be a sign of a very serious depression and I would definitely want to get him evaluated by a medical doctor as soon as possible, so call County Mental Health and get him there as soon as you can.

CAVANAUGH: Dr. Gordon, when is it time to seek professional help for a depressive state?

DR. GORDON: Well, I think if you’re feeling it’s something that you’re either overwhelmed by or you just feel you want to talk with somebody about what’s going on. It’s really very much of a – it’s each person’s decision. Some people are more comfortable dealing with things on their own, but I think that the huge – the barrier that we sometimes see – one of the projects we’re doing at the Center for Mind Body Medicine is working with military returning from Iraq and Afghanistan and there’s a lot of stigma about seeking out a mental health professional. I think part of that is, indeed, the fault of the mental health profession, that we made it into, you know, such a terrible thing to have, you know, one or another condition and part of it is, of course, perhaps a larger part, is our society which sees that, you know – believes that you have to be so strong and so self-reliant. So the major issue that I find is helping people get over their fear of appearing weak or their shame about looking for help and, you know, we ought to understand that if you feel you want help, that’s the time you should be looking for help and that’s the time you should be reaching out and then you and the person to whom you’re reaching out can come to a decision together about what’s most appropriate for you, how much help and what kind makes sense.

CAVANAUGH: Dr. Gordon, I know from your book that you’re somewhat uncomfortable with the idea of depression being categorized as a disease. Why is that?

DR. GORDON: Well, I don’t think, number one, the evidence is not there. If you really look at it very closely, what you see is that the hard evidence that depression is a disease—and it’s often compared to type I diabetes, insulin dependant diabetes—it’s just not there. You don’t see consistent biological changes in the brain of people who are depressed the way you see consistent biological changes with type I diabetes. The genetic contribution is real but it’s actually small for depression. It is – some people are more likely to become depressed. But even more importantly, looking at depression as a disease unfortunately leads too many doctors and too many people down the path of, well, it’s a disease and if you prescribe insulin for diabetes, then you need to prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other – like Prozac or Paxil or other drugs for depression. And it’s a kind of one-to-one equation. And I think the important thing there is, first of all, the drugs do not work very well. For many years, the pharmaceutical companies only published the positive studies over the last – the studies that showed the drugs worked about 60% better than sugar pills. Over the last few years, several different groups of researchers have looked at the unpublished studies and when you put together the ones the drug companies did not publish but the FDA has on file, and when you put them altogether what you find out is that drugs work little if any better than placebo.

CAVANAUGH: Well, that – there…

DR. GORDON: Sugar pills. That doesn’t mean they don’t work sometimes for some people but if you look at it with a clear-eyed, scientific mind, they do not work very well. They have very significant side effects in about 60 to 70% of people, and they’re difficult to get off. You have real withdrawal symptoms often when you stop them.

CAVANAUGH: There are a number of people…

DR. GORDON: But…

CAVANAUGH: I’m sorry, Dr. Gordon, there are a number of people who want to join our conversation.

DR. GORDON: Sure.

CAVANAUGH: And I want to get David’s take on this. You know, I completely understand, Dr. Gordon, what he’s telling us but there are some people who are – credit pharmaceuticals, drugs, for getting them out of deep, longstanding depression so how should one decide if they need medication to treat a depression?

PETERS: I…

DR. GORDON: Well, from my point of view, and this – I make this, I think, very clearly in “Unstuck” and provide all the evidence, you start off with the most beneficial and least harmful approaches. So…

CAVANAUGH: And I want to get David’s input on this, too, if I may.

PETERS: Yes, well, I do agree. The evidence is there that for a lot of cases of minor depression medications are not the best route at all. Medications have saved human lives, let’s get that straight, and for severe cases of major depressive disorder, the evidence is that that’s where medications can be helpful. But for all the, well, it’s hard to call a minor major depression, but there’s depression that is debilitating, that it does change the way the body’s functioning but for those, good cardiovascular exercise is as powerful as any antidepressant and it has very good beneficial side effects. We’re also building great scientific evidence that nutritional supplements such as omega-3 fatty acids can be very, very good to help the brain be more resistant to depression. And cognitive behavioral therapy can be as powerful as any anti-depressant and these all have beneficial side effects whereas medication, when you rush to medication, you’ve got a lot of negative side effects. And as I’ve said on this show a number of times before, Maureen, that one of the worst ways to treat depression is to go to your general practitioner and he says, well, here’s some Prozac, come back in 30 days. This usually leads to people having side effects they’re uncomfortable with, they stop their medication, they think they tried it and they say, it failed, I’m miserable. They blame themselves, and what they really needed was to go to a therapist first to talk their way through. Sometimes what they’re experiencing is not a major depression but a deep sadness because of real life circumstances that need to be worked through with a therapist.

CAVANAUGH: Well, I’d like to take a few phone calls. There are so many people on the line. John is calling us from Cardiff. Good morning, John. Welcome to These Days.

JOHN (Caller, Cardiff-By-the-Sea): Hi.

CAVANAUGH: Hi.

JOHN: I’m calling regarding – so I was a successful high school student at La Jolla Country Day and I went into the drama program at New York University and that’s kind of when I first started experiencing symptoms of actually bipolar depression but my symptoms were primarily in depression although I was later diagnosed with bipolar I, and I was eventually hospitalized in my second semester. And I wanted to hear your professionals on the line address, you know, what you thought about support for college students who are experiencing depression and bipolar depression in their late, you know, late teens and early twenties and what support there was and whether, you know, you thought it was sufficient within the collegiate system and, you know, whether people were reaching out enough and kind of some of those issues because, you know…

CAVANAUGH: Yeah.

JOHN: …over time that’s really turned my kind of world upside down and now as I’m reapplying to colleges it’s kind of a tricky issue because I’m – you know, it’s something almost as I talk to college counselors, they’re saying don’t talk about that even within your essays because…

CAVANAUGH: Gotcha. Gotcha, John. Thank you. Thank you for that. And, Dr. Gordon, you were a college student and depressed. Is there enough support given to younger people, young adults who come down with depression?

DR. GORDON: Well, from one of the things that I think is really important – I would say no. I think that there’s a – in some colleges, I have been told, that between 25 and 50% of the freshmen class are on anti-depressants drugs, which I find totally staggering but I’ve been told that repeatedly at different colleges. So that’s not the kind of support we’re thinking of. I think one of the things that we have done at the Center for Mind Body Medicine and that I describe in “Unstuck” and have found very successful is creating groups, groups for young people and groups for older people as well, in which you can share what’s going on with you with others who are in similar situations and in which you can learn basic techniques of self-awareness and self-care: relaxation techniques, guided imagery, physical exercise, dance, expressing yourself with drawings. These group situations are providing tremendous support for people at the same time they’re giving them independence. And I think this is one of the things that colleges need to explore much more. Too often, in college, you know, you go to the college health service and you do get the pills, just the way you do…

CAVANAUGH: Right.

DR. GORDON: …just as David was talking about.

CAVANAUGH: Right.

DR. GORDON: Just the way you do in the primary care doctor’s office.

CAVANAUGH: David.

PETERS: Yes, I fully agree. What we see is a lot of people who are experiencing depression really are – it’s brought on by tremendous alienation and rather than give them a pill, they need to be given circumstances in which they can find more richness and meaning in their life and group support is really where that’s at. The percentage of people on antidepressants is really terribly unfortunate because that number of people are not also getting therapy at the same time.

CAVANAUGH: Let’s get in another call. Gretchen is calling from Escondido. Good morning, Gretchen. Welcome to These Days.

GRETCHEN (Caller, Escondido): Hi, good morning. Thank you for taking my call.

CAVANAUGH: You’re welcome.

GRETCHEN: So I am a board member with Post-Partum Health Alliance and I’m so grateful for your conversation and I’m so grateful for the first half hour of the show. I just wanted to call and say that I completely agree, the comments and description of the symptoms with depression are very accurate. I love Dr. Gordon and David’s descriptions. I think they’re very helpful for people who are experiencing it to realize, yeah, that’s what I felt like. What I wanted your listeners to know is that this terrible experience happens for one in eight women following the birth of a child and it doesn’t necessarily have to be their first newborn. It could be their second or third child. But one in eight women or about 15 to 20% are estimated to experience different levels of post-partum depression. And the stigma that occurs in different groups like the military was mentioned and college students were mentioned, for women it’s particularly difficult when they’re supposed to be thriving and taking on their primary role that in society is really expected to be an excellent experience and it’s very difficult when it turns out to be difficult, you know?

CAVANAUGH: Thank you. Thank you for that, Paula (sic). Yes, David.

PETERS: Well, as Gretchen pointed out, the percentage is surprisingly high for the risk of post-partum depression and I would suggest what we really need to do is plan ahead for the risk of post-partum depression. Women who are pregnant should be getting really good nutrition. They should be taking omega-3 fatty acids to help support their brain. The should be getting lots of cardiovascular exercise so their body is in tune – as well-tuned as possible, and then getting group support and attention immediately following the birth. We should assume that it’s a regular risk. And it can be treated, hopefully without medications early on. But, yeah, it’s very confusing to family members when a mother of a newborn is clinically depressed but people don’t expect it and they get very confused.

CAVANAUGH: Dr. Gordon, we have only about 30 seconds left. I’m sorry about that. I was going to wonder, though, do you think of drugs as just one of the arrows in the quiver, as it would be, to fight depression?

DR. GORDON: I’m sorry. Say that again?

CAVANAUGH: Do you think of drugs as only one of the ways, perhaps a last resort, to fight depression?

DR. GORDON: Well, you know, I think that depression is – basically, it’s a wake-up call. It’s letting us know that our lives are out of balance and that there are things that we need to do to put our lives socially, biologically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually back in balance and that our work as helpers and healers is to help people do that, and that the last resort in that could be the use of antidepressant medication when it’s absolutely needed. But that primarily we need to understand that depression is a part of our life’s journey and that’s the journey that I talk about in “Unstuck” and try to guide people on. That’s the journey I think that David is talking about as well.

CAVANAUGH: Thank you, Dr. Gordon.

DR. GORDON: That’s our primary job.

CAVANAUGH: Thank you so much. I’m sorry I have to cut you off there but we’re out of time. David Peters and Dr. James Gordon, thank you so much for speaking with us. I really appreciate it.

PETERS: Good to be with you again.

DR. GORDON: Thank you both.

CAVANAUGH: And if you would like to comment on what you’ve heard on These Days, go online, KPBS.org/thesedays. You’ve been listening to These Days on KPBS.