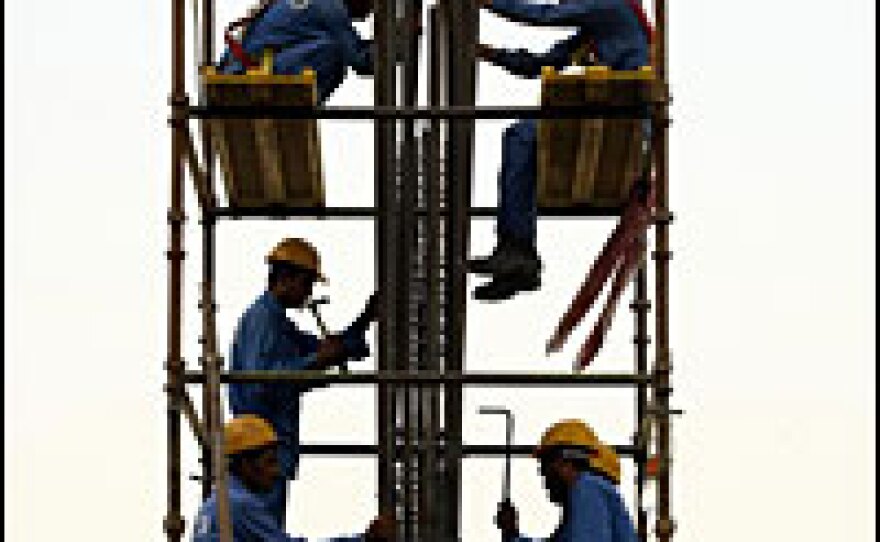

The phenomenal construction boom in the Persian Gulf states in recent years would not have been possible without the cheap labor supplied by millions of workers from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and other nations.

With some projects facing delays or even cancellation because of the current credit crunch, new questions are being raised. Are Gulf states prepared, for instance, to deal with mass layoffs and huge numbers of unemployed expatriate workers?

Although the growing understanding that the international financial crisis will not spare the Gulf has dampened spirits there, it's still hard to find a Dubai hotel room that's not surrounded by a cacophony of construction noise.

One worker on a project on the busy Sheikh Zayed road in Dubai, who gives his name as Mahmoud, says his project, part of the new metro system that's due to be completed in 2010, seems secure. But he says he worries about some of his fellow laborers.

In his very rudimentary English Mahmoud says the pay is poor, the conditions are harsh and some companies keep the worker's passport and two months pay to keep him from running away. If the work dries up, he says many people will be at the mercy of their companies to get home.

Analyst Mustapha Alani at the Gulf Research Center says he doesn't think people in the oil-producing states of the the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC, are prepared for a sharp downturn in development activity — neither the developers, the investors nor the migrant workers who could be hit first and hardest.

"We're talking about 6 million Indian workers employed in the GCC," Alani says. "Possibly 50 percent of this workforce — they're going to lose their jobs in the region. And either they have to stay as illegal immigrants or they have to go back to their country to seek employment."

On the outskirts of the city lie the labor camps — cramped, dirty, two-story concrete barracks that sleep six to 12 to a room, according to human rights activists. Young men hawk cell phone bargains, offering calls home to India, Pakistan or Bangladesh. Men line up patiently to wash themselves; a Dumpster sits in a great pool of standing water.

Stark as they seem, labor advocates say these are far from the worst conditions in the Gulf. A closer look at the tiny rooms finds each one equipped with an air conditioning unit that the laborers say do work in the brutal summer heat. After two years of strikes by angry workers and condemnations by international nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, the larger companies have invested in improvements for their workers.

Chad Haines, assistant professor at the American University in Cairo, has studied the plight of Gulf migrant workers. He says the first impact of the coming downturn and tight lending market could be to put those recent modest improvements at risk.

"It becomes an opportunity for a lot of the corporations, then, to not follow up on laws that have been passed in the last couple of years, drawing attention to the issues of exploitation there," Haines says. "This might be an excuse then to backtrack on a lot of that."

Many economists argue that Gulf states have the cash and the incentive to soften the regional impact of the financial crisis, and they doubt that governments here would allow the streets to be flooded with unemployed South Asians if there is a sharp downturn.

But that raises another troubling question: Is Pakistan, already struggling with political unrest and terrorist attacks, ready to absorb millions of unemployed young men back into its population? The leaders of this land of dazzling wealth and desperate poverty hope they never have to learn the answers.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))