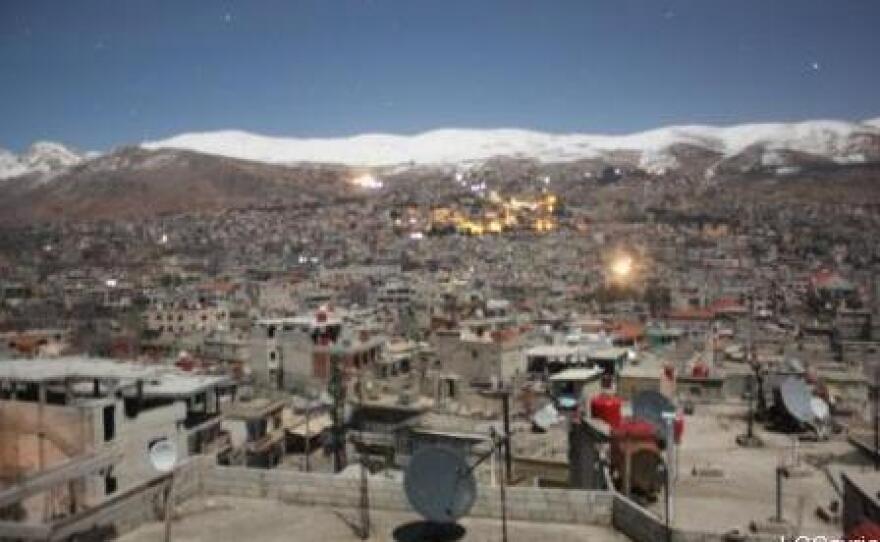

By the time Syrian troops moved into Zabadani, one of the last rebel strongholds near the Lebanese border, Kamal Labwani was in Sweden. Labwani, a doctor and a long-time democracy activist in his mid-50s, had been running a family medical clinic in the mountainous resort town a half-hour drive from downtown Damascus.

Zabadani was the only Syrian town that was under the opposition's full control during the 10-month rebellion. In January, the regime was forced into a truce because the army couldn't dislodge the rebels. But now Syrians troops are back, and Zabadani is under threat again.

"They got used to living free," Labwani says on a Skype call from Sweden. "There was a council, and it was elected. My clinic was the center of the new government."

The town was organized and run by a 28-member council, which coordinated with rebel troops known as the Free Syrian Army, Labwani says. These armed deserters drove up the potential costs of a direct attack on the town. In a war of attrition, the regime risked more defections every time there was a new offensive.

Labwani says he gets messages from both sides.

"The majority of the soldiers are against this," he tells me. Syrian officers tell him that they are ready to withdraw and support the revolution — but that would put their own families at risk.

Labwani says that 25 percent of Zabadani has been destroyed by shelling and fighting. A humanitarian crisis is looming, he says.

I first met Kamal Labwani in the summer of 2005, when the resort town was filled with Saudi tourists. The farms and fragrant orchards were in full bloom. He'd just been released from a three-year prison sentence, most of it spent in solitary confinement.

As we drove to his clinic on the town's main street, he told me how he conducted his practice. This is what I wrote in a story from that summer:

"He knows every one here, their medical histories, all kept on files inside his head. He doesn't want the security police to know anything about anyone. Even their disease. So he has no staff."

Labwani was sent to prison again later that year. In 2005, he was the first Syrian dissident invited to the White House. The honor cost him a five-year prison term when he returned to Damascus.

He was released in November, 2011 and fled to Jordan, then to Sweden, where he continues to play a vital role in advising Zabadani's local leadership. With the failures of Syria's external opposition to offer a coherent plan and a military leadership that seems to have no ties to local commanders, local leadership is all that matters for most Syrians facing the wrath of the government.

Labwani says that in recent days, some officers have offered a deal to spare the city. They promised to stop the shelling — if Syrian tanks can patrol the central streets and claim a media victory for the regime.

"Take pictures and then we can withdraw," is what the officer has offered, says Labwani. He wants no part of a propaganda coup for Syrian state television.

"I've asked them not to negotiate," says Labwani. "They are liars," he says, referring to the regime and the officers who carry out the assaults. He puts his trust in the local council and rebel forces, lightly armed men who are slowly changing the balance of power.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))