In a monastery on the Tibetan plateau, monks swathed in crimson robes chant under silk hangings, in a murky hall heavy with the smell of yak butter. Photos of the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama — seen by China as a splittist — are openly displayed, as if in defiance. But Chinese security forces have tightened their grasp on this region, and monasteries appear to be emptying out, gripped by an atmosphere of fear and loss.

In one town, monks boycotted the usual Chinese New Year celebrations at the end of January as a mourning gesture, refusing to set off fireworks.

"Too many of our people died this year," one monk told me, referring to nearly two-dozen Tibetans who have set themselves on fire as a protest against Chinese repression. Identifying details have been removed to protect those who talked to NPR.

Police cars patrol the streets here, and on the morning of the new year, security forces took pre-emptive action.

"Paramilitary forces from elsewhere were sent here," says the monk. "There were tanks, too."

"They closed off all the exits to our monastery and didn't let us leave," says a second monk. The paramilitary police withdrew afterward, but monks say plainclothes police remain inside the monastery. The monks listen secretly to Voice of America's Tibetan service news every night, despite feeling almost physical pain at the bleak news.

There's a Buddhist prohibition against violence or suicide, but these monks are of one mind on the self-immolations.

"What they did was great," says the first monk. "Yes! Yes! Yes!" says the second. "That's why we didn't mark the new year — because of them."

A Sign Of The Times

Those who have set themselves on fire include Sonam Wangyal Sopa Rinpoche, a 42-year-old tulku, or "living Buddha," who ran an old people's home and an orphanage in Darlag, Golok prefecture, Qinghai province. He left behind a crackly audio recording of his last message, saying, "This year in which so many Tibetan heroes have died, I am sacrificing my body to stand in solidarity with them. ... I pray that the Dalai Lama will return to Tibet."

On Jan. 8, standing in front of a police station in Darlag, he drank kerosene. Then he set himself on fire.

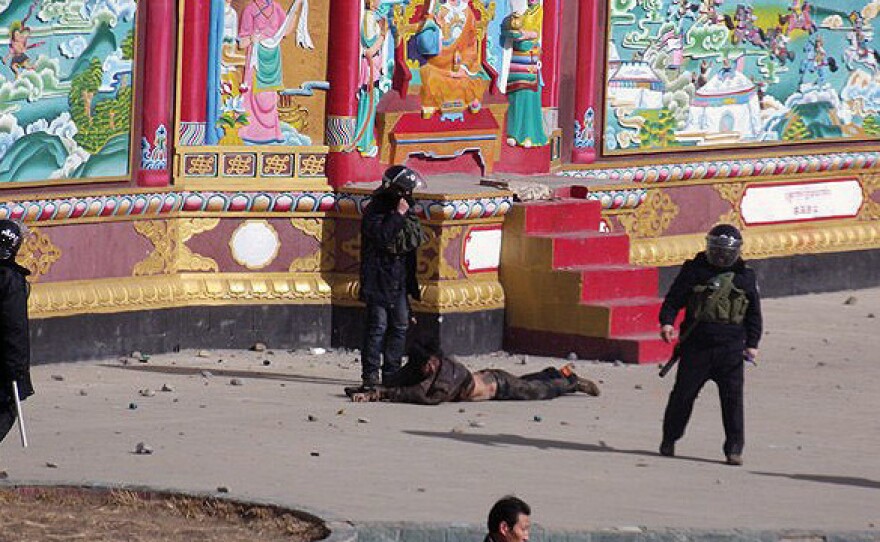

It's a sign of Tibetan desperation, and Tibetan radicalization, with the anger bursting into a number of peaceful protests in Qinghai province. In neighboring Sichuan province, at least seven Tibetans were shot dead by security forces and more than 60 wounded, according to exiled advocacy groups, when police put down protests late last month. Chinese state media said police fired in self-defense.

China accuses the Dalai Lama of instigating unrest. A foreign ministry spokesman blames what he calls the "Dalai Lama clique," saying its behavior in not condemning self-immolations is "a disguised form of violence and terrorism, as the group has actively tried to pursue separatism by harming people."

The last time the plateau was in such turmoil was in 2008, after race riots between Tibetans and Han in Lhasa left 19 dead. Since then, Beijing has tightened its controls on the monasteries it sees as the crucible of unrest.

Government Control

At Ta'er Si, also known as Kumbum monastery, ticket machines beep as tourists swipe through. This monastery is one of the main schools of the Dalai Lama's sect. Close to the city of Xining, it has also become a major tourist attraction, with Chinese visitors paying almost $13 a head. There are no pictures of the Dalai Lama here — a testament to Chinese efforts to use "patriotic education" to divorce Tibetan Buddhism from its spiritual leader.

"Lots of tourists ask me, but the monastery doesn't allow us to talk about these things," says our Tibetan tour guide, reluctant to discuss the Dalai Lama. "We're supposed to talk about the history and culture of the temple, the artwork, the lives of the monks, their food and customs."

Here, only a handful of monks are visible, selling tickets or sweeping floors. Officially, 600 monks live in Ta'er Si, but that's less than half the monastic population before the unrest in 2008.

Across the plateau, monasteries are depleting; the authorities used administrative controls to send "unregistered" clergy home after the unrest. Official Chinese reports show the number of monks at Sera monastery in Lhasa has been reduced to 460, less than half what it was before 2008. In Drepung monastery, another major teaching center, the number was halved to 600 after the management sent home 700 visiting monks.

"The population in monastic institutions has decreased tremendously," says Lobsang Nyandak, the representative of the Dalai Lama in the U.S. "Either they have been expelled for not obeying the Chinese commands, and many voluntarily left the monastic institutions because they cannot tolerate the repression the monks and nuns have to undergo."

That includes submitting to new monastery committees that are headed for the first time not by monks but by government officials. New management mechanisms introduced in November offer incentives to monasteries such as paved roads, electricity and piped water, but also place full-time government cadres inside the monasteries. Inside the Tibet Autonomous Region itself, monasteries have been ordered to display pictures of four Chinese leaders, including Chairman Mao Zedong.

"It's to do with the unrest after the March 14 [riots] and the self-immolation of monks," says academic Wu Chuke from Minzu University of China. "That such incidents should repeatedly happen inside monasteries shows that our former management system was problematic. The [former] management committees comprised of monks perhaps don't stand on the side of the government's interests."

As an example, he says, he believes monks are ill-equipped to deal with monasteries' increasing economic revenues: "As the money mounts up, I've seen monks with the most up-to-date mobile phones and cars. If the monks are solely responsible for monasteries, there may be many problems. The senior monks may get very rich, but that would create a big wealth disparity within the monks."

But others, like Robbie Barnett, a professor of modern Tibet studies at Columbia University in New York, see this policy shift as having wider importance.

'Relationship Between State And Society' Changed

"This may be more significant than incidents of unrest," Barnett says. "It's for the long-term, and it's an indicator of a considered, strategic shift in policy, whereas the use of military force and troops seems more of a panic reaction to the recent surge in protests."

"It is also unprecedented in that it changes the relationship between state and society. For 30 years, there's been an effort to ensure the party is not directly involved in religion. That's all gone now."

At a different monastery on the Tibetan plateau, wooden prayer wheels creak as pilgrims spin them. Police cars drive up and down outside the monastery. Inside, there's no security presence. All appears calm, tranquil even. But this place has seen unrest, and panicky conversations show the underlying terror.

"We don't have the right to speak freely," one monk says. "We are scared. If we talk to you, they'll arrest us."

Another man butts in. "You speaking with the monks makes them truly scared," he says. "They could get shot."

He makes the shape of a gun with his fingers, and puts it to his head, pulling the trigger. Then, in case of any misunderstanding, he repeats the gesture.

It's a sign of how sophisticated the apparatus of control has become. Parts of the Tibetan plateau, like Aba in Sichuan, the epicenter of the self-immolations, have become heavily militarized, with riot police armed with spiked clubs and fire extinguishers on every street. Other monasteries are still open to praying pilgrims and chanting monks, but there the repression is largely invisible and internalized.

And the Chinese party line is to draw up battle lines; officials inside Tibet have been ordered to get ready for "war against secessionist sabotage."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))