Federal authorities are rapidly expanding the use of a little-known smartphone technology to monitor hundreds of thousands of individuals facing deportation across the country. More than 5,000 people in San Diego and Imperial counties are now monitored through the program — up from about two dozen less than three years ago.

Immigration authorities’ use of SmartLINK, which began in 2018, has exploded in the past year alongside concerns that the program could be surreptitiously collecting, sharing and monetizing data about its users.

SmartLINK — one of three alternative programs that the Biden administration has leaned into as it promises to reduce populations in detention centers — uses biometric information such as facial comparison and GPS to track individuals under watch of U.S. Immigration and Custom Enforcement, or ICE.

Federal officials have billed SmartLINK as a more humane and cost efficient alternative to traditional detention, allowing individuals to await their court proceedings at home rather than in one of ICE’s detention centers.

The benefits of SmartLINK include increased court appearance rates and compliance with release conditions by providing reminders for court dates, resources for immigrants and direct messaging between immigrants, officers and case specialists, according to an ICE spokesperson.

But critics say SmartLINK and other programs have had the effect of expanding ICE’s reach in the lives of immigrants, including those who would typically be released into the community without supervision to await their immigration hearings.

“What is clear in our communities and over the past couple of years is that these are not alternatives to detention,” said Cinthya Rodriguez, a organizer with Mijente, which advocates for “Latinx rights, justice, and radical change.” Latinx is a gender neutral term describing people of Latin American heritage.

“They're an extension of the violent and massive detention system,” Rodriguez said.

Immigration advocates are sounding the alarm on what they say is a rapidly expanding “e-carceration” system — fueled by surveillance technology used in alternative detention programs — that could be quietly collecting sensitive information on more than 200,000 individuals and their personal networks across the country, including U.S. citizens and legal residents.

Mijente, along with two additional immigration and incarceration reform advocacy groups, filed a lawsuit against ICE in April demanding that the agency reveal what data SmartLINK collects from the user, who the data could be shared with and the extent of the monitoring conducted through the app.

Congressional Democrats have pushed back against the program, calling for a reduction in its use and diverting funds toward community based supervision programs, where nonprofits step in to provide social services and legal orientation.

Privacy experts say most concerning is what the company and ICE have yet to reveal about what they’re collecting and sharing.

“There's so much that we don't know, and three years into this program, the fact that we don't know this information is quite frankly staggering,” said Saira Hussain, staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital civil liberties nonprofit.

“We understand what those traditional forms of incarceration and e-carceration entail, but this is sort of a new horizon. It's a new frontier,” Hussain said.

Explosive growth in SmartLINK surveillance

Immigrants enrolled in SmartLINK log into the app from their own smartphone or a locked cellphone, called BI Mobile, provided by ICE that has no other capabilities.

BI Incorporated, the company that created SmartLINK, contracts its employees with ICE to run the program as case specialists. Those tracked under SmartLINK can message and video call their case specialist, upload documents, look up community resources and see upcoming court dates, according to BI Incorporated’s website.

The app uses “facial comparison technology” and “enables officers to confirm location, curfew and travel restriction compliance,” according to BI Incorporated. The level of supervision assigned to users is decided by ICE agents based on an individual’s immigration status, criminal history, compliance history and other personal factors.

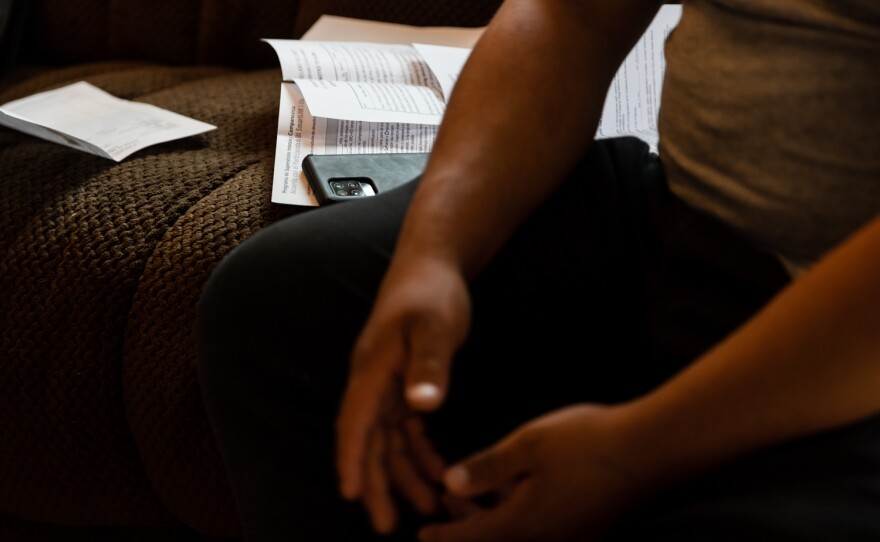

One SmartLINK user who spoke to inewsource said he has regular check-ins once a week where sends a photo of himself through the app. He’s also required to check in at unscheduled times whenever the device alerts him, he said.

He requested anonymity because his case is ongoing and he fears federal agents may retaliate against him or his family for talking to the media.

He said he is required to stay within a 77-mile radius as part of his SmartLINK program. As a result, he’s had to turn down construction jobs that happen outside of the zone, making it more difficult to pay for legal services he had to seek for his defense.

When ICE enrolled him in SmartLINK, they told him they could see everywhere he went, he said.

“It just puts a sense of fear in me that at any given moment I can be taken into custody again,” he said.

The number of people using the SmartLINK to check in with ICE has exploded quickly, according data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC, at Syracuse University.

Last April, about 1,200 individuals were using SmartLINK in San Diego and Imperial counties to check in with ICE. This past April, that number passed 5,000 — quadrupled in one year

Federal funding for the program is on the rise, too. Over the past decade, ICE’s budget for alternatives to detention has ballooned from $6.5 million in 2012 fiscal year to $440 million in the current one.

The Biden administration this year asked for a 17% increase from the 2022 budget to expand ISAP “in lieu of a sustained reliance on detention.”

ICE’s latest five-year contract with BI Incorporated, a subsidiary of the private prison company Geo Group, topped $2.2 billion to operate the SmartLink program, plus ankle bracelet monitoring and telephonic reporting.

Critics also accused ICE of forcing individuals onto SmartLINK who normally would not be subject to supervision after being released from custody.

An ICE spokesperson said alternatives to detention such as SmartLINK “may be appropriate” for those released from custody on their own recognizance, orders of supervision, parole or bond.

Data collection, sharing concerns grow

Immigrant and privacy advocates foresee alarming consequences in ICE’s expanding surveillance network. They say ICE is using SmartLINK to collect sensitive data about individuals, and their networks, without providing details on what information exactly is collected and who it could be shared with.

ICE and BI Incorporated have provided inconsistent information on when a user's location data is being tracked, according to a March report in The Guardian, which relied on interviews with former BI employees, users of the program and company policies.

“That really leads to a lack of trust in the app and lack of trust that it's going to be used in a responsible manner,” said Hussain, the Electronic Frontier Foundation attorney.

The company also encouraged data sharing between government agencies and collected large amounts of data about thousands of users through the app, The Guardian reported.

BI Incorporated’s online privacy policy outlines a broad range of data it collects from its users. It also includes an explanation of how the company uses that information and when it may disclose it to another party.

However, some of the explanations are vague.

For example, BI Incorporated can release personal information to its “subsidiaries or affiliates” or simply “if we believe disclosure is necessary or appropriate to protect the rights, property, or safety of BI Incorporated, our customers or others.”

It may also disclose data “to contractors, service providers and other third parties we use to support our services.” The company said those third parties are bound to keep that information confidential.

For California users specifically, BI Incorporated’s policy says the app has “collected or received” education, employment, financial and medical information.

Users provide this information directly to the company or “automatically when you use the app,” and the information is used to verify identity or to “provide services to in connection with your community supervision.”

BI Incorporated referred requests for comment from inewsource to ICE.

ICE did not answer specific questions from inewsource concerning SmartLINK’s data collecting or sharing, but said the agency is “committed to protecting privacy rights, and civil rights and liberties of all participants within the Alternatives to Detention program.”

As the federal government expands its use of smart technology, promoting it as safer and more effective than physical detention, advocates see privacy concerns extending beyond the individuals using the technology.

“There is a misconception that using smart tools or tools that use technology for enforcement purposes are not as invasive as some of the physical tools,” said Pedro Rios, director of a migrant rights program at the American Friends Service Committee.

Oftentimes, border surveillance tech captures information on broader communities, not only immigrants under ICE watch.

A recently-published study from the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy & Technology found that ICE operates an expansive and far-reaching surveillance network capable of tracking three out of four adults in the United States.

Julie Mao, deputy director at Just Futures Law, one of the groups that filed the lawsuit against ICE over SmartLINK data, said in a border county such as San Diego, communities “whether immigrant or not” have already been subject to surveillance.

“We think in this moment, ‘Why are immigrants complaining about this version of surveillance? They should just be happy not being detained or deported.’”

But the reality is, she added, the tools used to surveil immigrants today “can be multiplied, transferred and repurposed for other communities and other reasons.”