Before the Caldor Fire sparked one year ago this week — before its 150-foot flames devoured century-old ponderosa pines in California’s Sierra Nevada, and before it destroyed more than 400 of the 600 homes in Grizzly Flats — Mark Almer had a plan.

The 60-year-old retired fire inspector had spent over a decade fireproofing his Grizzly Flats home, trading wood deck boards for composite material and replacing traditional siding with a protective cement shell.

“Hardening the home is huge,” he said. “But it’s just one piece of the puzzle.”

Almer had an even bigger plan to protect his community.

For more than a decade, he’s led the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council, a group of two-dozen volunteers that raised money for wildfire mitigation projects, educated the town’s roughly 1,400 residents about defensible space and regularly gathered local, state and federal fire officials to help improve their fire response plan.

The Caldor Fire would be the council’s ultimate test.

On August 16, 2021, two days after the fire ignited, gusty winds pushed the flames out like billowing sails, spreading across thousands of acres overloaded with shrubs and trees in the neighboring Eldorado National Forest.

Almer and his wife didn’t grab much on their way out the door. Their six cats, corralled into six crates, took up most of the car space.

He was more concerned about making sure everyone else in the community got out safely. Before the official evacuation order came, Almer called his next door neighbor, Victor Diaz.

“I thought we still had time,” Diaz said in a recent interview.

But Almer’s voice indicated otherwise. An even-keeled speaker with a clean vocabulary, Almer barked his warning with a rare four-letter word that Diaz declined to repeat.

“You need to get the beep out,” Diaz recalled.

Diaz, his wife, their six kids and the family dog raced down Grizzly Flat Road in a two-car caravan, leaving behind the fire’s red glow and the home they’d never see again.

Many residents knew this day might come. At a community meeting in the early 2000s, the U.S. Forest Service, with chilling foresight, had warned that a wildfire mirroring the Caldor Fire’s burn progression could easily wipe Grizzly Flats off the map.

In the years that followed, the Forest Service took steps to prevent such a catastrophe. But a nine-month investigation by CapRadio and The California Newsroom, a public media collaboration, found that the Forest Service’s plan to protect Grizzly Flats fell far short:

- After the community meeting, the Forest Service took a decade to announce a comprehensive 15,000-acre forest management and fire mitigation plan, called the Trestle Forest Health Project. It aimed to “reduce the threat of large high intensity wildfire and threats to Grizzly Flat[s]” and other nearby landowners by removing excess brush and vegetation that fuel increasingly devastating wildfires, according to project documents.

- The Forest Service originally committed to finishing the Trestle Project by 2020 — a year before the Caldor Fire would later ignite. Due to a complex web of regulatory delays, logistical challenges and resource shortages, the agency pushed back the completion date to as late as 2032 — three decades after its initial warning to Grizzly Flats.

- The Forest Service’s data overstated Trestle Project accomplishments, claiming the agency completed work on at least 24% of the project before the Caldor Fire. Original analysis of corrected Forest Service data provided by the agency shows only 14% completion. The agency confirmed the inaccurate information had been online for more than a month; it updated its database less than a week before publication of this story.

- The corrected data also suggests that in the decade-and-a-half leading up to the Caldor Fire, the Forest Service completed 15,000 acres of fuel reduction work within a five-mile buffer around Grizzly Flats — coincidentally, the same number of planned acres in the Trestle Project. However, the actual coverage of that work was limited to 5,800 acres because of the agency’s decades-long and highly criticized practice of counting repeat treatments on the same parcel. Furthermore, the majority of that work occurred several miles from the town’s border.

- The Forest Service failed to complete sections of the Trestle Project along the southern border of Grizzly Flats, identified as “first priority” due to the area’s susceptibility to wildfire. Instead, the agency prioritized removing trees — often far from the town’s borders and not a part of the “first priority” area — that generate revenue.

- Despite more than five requests, the Forest Service failed to provide complete data on its national wildland fire management budget, citing a recent data transfer in which it lost some information from the past two decades. The agency also could not provide similar budget information at the regional and forest level, saying numerous changes to the budget structure and process over the last 20 years made retrieving the data especially difficult and would render any analysis “incomparable.”

Agency leaders say a slew of hurdles stood in the way of the project’s completion: limited funding, pushback from environmentalists and fewer opportunities to complete essential prescribed burns due to staff shortages and climate change.

“I am committed to doing everything I possibly can to mitigate [wildfire risks] on our landscapes,” said Forest Service Chief Randy Moore in an interview.

When asked if his agency bears any responsibility for the devastation in Grizzly Flats as a result of the stalled Trestle Project, he cited financial constraints.

“I mean, do[es] anybody bear any responsibility for not having the budget to do the work that we need to do?”

The Eldorado National Forest falls under the Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region, which Moore led from 2007 to July 2021, when he was appointed chief by President Joe Biden’s administration. He assumed office just a few weeks before the Caldor Fire ignited. Moore declined multiple opportunities to say whether completing the Trestle Project would have resulted in a different outcome in Grizzly Flats.

“I’m not really sure why we keep talking about that question,” he said.

After reviewing this investigation’s findings, a dozen sources — including wildfire experts, career firefighters, former Forest Service officials and residents — said they believe Grizzly Flats would have stood a better chance of surviving the Caldor Fire if the Trestle Project had been completed.

Among the sources was one of the project’s key architects, former Eldorado National Forest District Ranger Duane Nelson.

“There would have been a very high probability that Grizzly Flats would not have burned in the Caldor Fire” if the Forest Service completed the Trestle Project, Nelson, 67, said in an interview. “It could’ve meant survival.”

An Early Warning

On a chilly day this past March, Almer sat in his idling white Toyota Tundra pickup next to where the Grizzly Flats Community Church once stood. The small yellow chapel bordered by white picket fencing had vanished, along with most of the community, in the Caldor Fire’s wake. From the driver’s seat, Almer observed rows of charred metal chairs facing an absent pulpit.

“It’s kind of eerie,” he remarked, “as if they were still ready to accept parishioners.”

The church is where local Forest Service officials, in the early 2000s, held their town meeting to warn residents about wildfires. Grizzly Flats is surrounded on three sides by the Eldorado National Forest; the agency acknowledged that a devastating fire would likely rip across federal land before reaching town. Using a PowerPoint to show fire modeling scenarios, they gamed out all the ways Grizzly Flats could go up in smoke.

“It was important for us to start talking to people and make sure that they had the information that we had about what our models were showing,” said Kathy Hardy, a former district ranger who attended the meeting.

One scenario showed what would happen if the fire started a few miles south of town in the Eldorado National Forest, close to where the Caldor Fire would ignite years later.

“The modeling said that it would take out Grizzly Flats within about 24 hours,” Almer recently recalled. “Well, 20 years later, that’s pretty much exactly what happened.”

The Forest Service has not provided records related to the meeting in response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed in December 2021.

As Forest Service officials flipped through presentation slides, residents shifted uncomfortably in their metal chairs. This was a town that had just installed its first all-way stop sign. The Grizzly Pines School had recently earned a Distinguished School Award from the California Department of Education despite having only 36 students. The place, in many ways, was idyllic — so remotely located and so small that it had no grocery store, no gas station, no diner, not even a local bar. Now, the Forest Service was telling them, with data to back it up, that their town and their lives sat in Mother Nature’s crosshairs.

Two Fire Plans, Two Timelines

Grizzly Flats wasn’t the only town in peril. For years, the federal government had been wringing its hands over the nation’s growing wildfire crisis. In 2000, wildfires burned over 7 million acres across the country — a stunning total at the time, and a harbinger for even worse years to come.

In response, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Department of the Interior — the agencies that managed much of the land that had been scorched — developed a National Fire Plan. It emphasized forest management and fuel reduction as key preventive measures. Methods traditionally used by the federal government include commercial thinning (cutting some trees to be sold as timber or wood pellets), removing brush with heavy machinery (a process known as mastication), and prescribed burning (intentionally setting lower-intensity fires that benefit the landscape).

To figure out where to put its resources, the Forest Service — which operates under the USDA — helped compile a list of communities nationwide at “high risk from wildfire.” It included thousands of communities, identified primarily for being in the “wildland-urban interface” or WUI, a term used to describe the intersection of developed land and the natural environment.

Buried on the list was “Grizzly Flat.”

(The town, throughout history, has been referred to as “Grizzly Flat” and “Grizzly Flats.” The latter is more common.)

Shortly after the Forest Service’s cautionary meeting at the local church, Almer and two-dozen other residents formed the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council. They set up an informational phone line, installed a nine-foot community bulletin board at the post office and started an adopt-a-hydrant program, which got residents to shovel out hydrants after snowstorms.

The council served as an essential community thread in the simple quilt of Grizzly Flats.

“There was no government, there was no mayor,” said Kathy Melvin, 78, who joined the council in 2007. “There was just the fire safe council, the church and the school. Everything kind of revolved around those entities because we didn’t have anything else.”

Within a couple years of its founding, the council commissioned its own community wildfire protection plan. The 74-page document laid out plans to clear evacuation routes and assist residents with defensible space around homes.

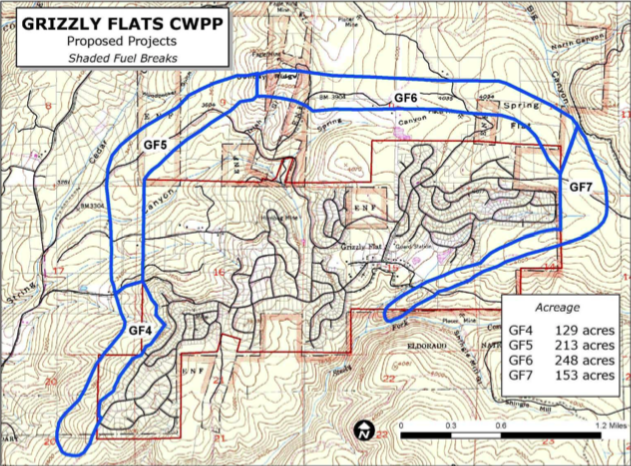

It also proposed a series of fuel-reduction projects, including an ambitious “shaded fuel break” in the shape of a horseshoe around Grizzly Flats. Shaded fuel breaks remove ground vegetation to reduce wildfire intensity and provide a staging area for firefighters. The horseshoe covered the east, north and west sides of town; the community was banking on the Forest Service to tackle fuel reduction work along the southern border to complete the protective buffer.

The plan would cost millions of dollars, and the council raised money however it could. An area couple hosted 150 people at their home for a wine tasting under paper lanterns and summer stars. The council held annual barbecues. What money it couldn’t raise, it made up for with grants.

The efforts paid off. Over the next 15 years, the fire safe council cleared more than 1,500 acres of fire-prone vegetation around town, completing almost all of the horseshoe fuel break at a cost of nearly $2 million. The council even earned national recognition for its productivity and wildfire mitigation work.

Meanwhile, most of the Forest Service land to the south of Grizzly Flats remained dense and overgrown — a reminder to residents that their community was dangerously exposed.

‘Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal’

As a district ranger in the Eldorado National Forest, Duane Nelson started each day with a clean, pressed uniform and aimed to clock out with dirty shirtsleeves and muddy boots.

“I wasn’t going to just be a ranger sitting in the office behind a computer all the time,” he said. “I made a promise to myself that I would be out looking at projects, checking up on crews or going by fire stations.”

His 38-year career in the Forest Service can be traced to a childhood vacation to the Rocky Mountains. Sitting in the back of his family’s faux wood-paneled Ford Country Squire, he watched hours of hypnotic prairielands roll by. All of a sudden, purple mountaintops pierced the horizon, surrounded by timber canyons.

“It’s an image that’s been in my head ever since,” he said.

Nelson earned a degree in forestry and left his Midwest roots behind, preferring the mountains and conifer forests of Northern California.

When he took over as the Eldorado National Forest’s Placerville District Ranger in 2007, he didn’t like what he saw. The majority of his district was dense, dry and prone to catastrophic wildfires — especially around Grizzly Flats.

A few years before Nelson arrived, the district had thinned and burned 1,000 acres to the south of Grizzly Flats, including areas along the town’s southern border. But other fuel reduction efforts were scattered and piecemeal, often deep in woods and miles from town.

So Nelson devised what he called a “big, hairy, audacious goal.” He wanted to reduce forest congestion across his entire district.

To do that, he said, “We needed to reverse this massive fuels accumulation that had developed over 100 years of overly aggressive fire suppression.”

Before the advent of modern firefighting, naturally occurring fires served the important role of balancing ecosystems and preventing the accumulation of fuels. For millennia, indigenous communities set fire to forests and wildlands for a variety of reasons, including hunting and cultural practices, which also kept the land in check. But according to fire ecologists and historians, the federal government’s century-long practice of snuffing out every wildfire, instead of letting them perform their natural role on the landscape, has left forests overloaded. Combined with hotter, drier conditions caused by climate change, the heavy fuel loads are spurring bigger, more destructive blazes.

Nelson helped devise the Trestle Project as a big step toward his goal. It would create a miles-wide fuel reduction buffer east and south of Grizzly Flats.

When the Forest Service finally announced the project in 2013, the agency sent a letter to residents describing 16,000 acres of planned work. (A miscalculation led to the document overstating the work by nearly 1,000 acres. The actual number was just over 15,000.) It laid out an expeditious — and optimistic — timeline. The analysis was supposed to take about a year, with the forest management work scheduled to wrap up by 2020.

Almost immediately the project encountered an onslaught of hurdles and delays.

“It’s sad to think about what could have been,” said Michael Wara, a climate policy expert at Stanford University who recently toured Grizzly Flats. “[If] all this work was done by 2020, Grizzly Flats might still be there.”

‘We Don’t Have That Kind Of Time Any Longer’

One of the most aggressive objections to the Trestle Project came from Chad Hanson, co-founder of the John Muir Project, a nonprofit that aims to protect biodiversity in national forests and fiercely opposes tree removal. One of Hanson’s primary concerns was the California spotted owl, which is designated as a “sensitive species” by the Forest Service.

In a written objection to the Forest Service in 2015, Hanson argued the Trestle Project would “pose a serious and unacceptable threat to owl populations on the Eldorado National Forest.”

Elsewhere, Hanson has argued that commercial tree removal could exacerbate wildfire intensity. Leading fire scientists have publicly pushed back against a number of Hanson’s claims; one expert even called his positions “self-serving garbage.”

The project’s 296-page environmental impact statement devoted dozens of pages to analyzing potential impacts on the spotted owl. The report also invited public comment that demanded thoroughly researched responses from the Forest Service. The agency developed alternative maps, taking into account spotted owls and sensitive species of frog and trout.

The Forest Service also put out other reports, including one that identified a likely ignition point very close to where the Caldor Fire would later start.

As the Forest Service spun out reams of paperwork, Almer reminded the agency that Grizzly Flats remained woefully exposed to wildfires that were growing more severe every year.

“The most aggressive treatment of the [Trestle Project’s] fire fuels is critical to preventing the ‘loss of our community,’” wrote Almer in a 2015 public comment about the project on behalf of the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council. “Everything that can be done, must be done.”

He followed up this plea with a 2017 letter addressed to Randy Moore, who at the time led the agency’s Pacific Southwest Region.

“Maximum treatment must be given to the defense and threat zones abutting Grizzly Flats … to prevent spot fires from a wildland fire igniting homes within the community,” Almer wrote in his letter.

In an interview, Moore said he did not recall the letter from Almer. The threat Grizzly Flats faced “is not unique,” he said. “I can tell you that that’s going to be common for a number of communities all across the West.”

The Forest Service acknowledges that its regulatory approval process for desperately needed forest management projects can be a slog. But trying to streamline it is a delicate balance.

As Scot Rogers, the current Placerville district ranger, said in an interview, it’s essential that “the American public has an opportunity to engage in the management of their lands.” But, he added, “That doesn’t necessarily mean that we need to get lost in a sea of analysis and unable to actually execute these projects — because we don’t have that kind of time any longer.”

The Trestle Project wasn’t approved until late 2017, more than four years after its announcement and more than a decade after the agency called the initial meeting at the church.

But by that time Duane Nelson, one of the project’s main architects, was gone. Burnout had set in, exacerbated by persistent staffing shortages. Sleepless nights left his nerves shot.

“If it’s hot, dry and windy, rangers don’t sleep,” he said.

Nelson retired in early 2017, a year before he’d originally planned. Before submitting his notice, he took a drive through his district, following the backroads that bisected dense tree stands. He wanted to see the condition of the forest before making his official decision. Driving through the Trestle Project area, he envisioned the southern border of Grizzly Flats cleared of brush and returned to something like its natural condition after prescribed burning.

“We had done a lot of good things,” he said, reflecting on his retirement. “But there was still a lot of work that needed to be done.”

Stalled Out

Over the next four years, the Forest Service completed only a fraction of the Trestle Project.

It called for fuel reduction across more than 15,000 acres of land around Grizzly Flats, but completed work on just over 2,000 of those acres.

Prescribed fire, considered crucial by fire scientists, was nowhere to be found. The project called for more than 10,000 acres of intentional low-intensity fire, but the agency only completed 136 acres of “pile burns,” the process of collecting and burning logs and vegetation that is widely considered much less impactful.

The agency instead prioritized commercial tree thinning, which generates revenue that offsets costs.

Generally, commercial thinning and other treatments designed to reduce fuel loads are a necessary precursor to prescribed fires, according to Rogers.

“Largely, we’re not going to be able to put fire on the ground before that work is completed,” he said.

But Trestle Project reports and Forest Service data show the vast majority of the planned prescribed fire was intended as the first treatment.

Wildfire researchers and former Forest Service officials say it’s disappointing the agency would focus on commercial thinning over other forms of treatment.

“The evidence that commercial thinning really reduces risk is not that good,” said Wara, the Stanford climate policy expert. “If you thin and then burn in an area, then you get dramatic risk reduction.”

Meanwhile, areas adjacent to the community that the Forest Service identified as “first priority” were left untouched and overgrown. One stands out: The highly overgrown — and highly combustible — southern border, which would have dovetailed with the buffer zone that Mark Almer and the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council worked on for over a decade.

“The part that didn’t get treated was the part we should have been most worried about,” said Hugh Safford, who spent two decades as the Forest Service’s senior ecologist in California before retiring in late 2021.

The steep, dense and dry south-facing terrain made it one of the more complicated parts of the project, but also the most essential, Safford noted.

Melvin, the longtime fire safe council member, lived on the south end of Grizzly Flats and shared a property line with the Forest Service for nearly four decades. Her house was among the first in town to face the Caldor Fire’s wrath.

She took defensible space seriously, clearing shrubs “down to the dirt” before every fire season. By contrast, she said, the nearby Forest Service land remained overgrown with trees, brush and highly flammable mountain misery shrubs.

Melvin kept her expectations about the Trestle Project in check.

“The history of the Forest Service, in the time that we lived there, was that everything took forever,” she said. “I wish they had done more.”

No Money, No Mitigation

In a series of interviews, Forest Service officials offered an array of reasons why efforts like the Trestle Project face delays and are sometimes not completed.

At the top of the list: Money.

“Let’s not make any bones about this,” said Chief Moore in an interview. “We do not have the funding to do the level of work that needs to be done out there.”

Compared to the soaring costs of preparing for and fighting wildfire, spending on hazardous fuels reduction has barely increased over the last 15 years when adjusted for inflation, according to incomplete data provided by the agency.

That doesn’t mean all projects struggle to secure funding. From 2008 to 2019, a partnership of private organizations and government agencies, including the Forest Service, pulled together $150 million and tackled 57,000 acres of fuel reduction around Lake Tahoe, not far from Grizzly Flats.

Chief Moore lauded those efforts around Tahoe during testimony before Congress in March.

“Last year, the Caldor Fire in California blew right through scattered small treatments on the Eldorado National Forest,” he testified, “then hit an area of treatment at-scale on the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit.”

The work, he said, allowed firefighters to engage with the Caldor Fire and keep it “from burning into South Lake Tahoe.”

The Forest Service repeatedly declined to — or could not — provide basic budget information for the agency’s nationwide wildfire management work, the Pacific Southwest Region and the Eldorado National Forest. The agency also could not provide funding information related to the Trestle Project.

In December, CapRadio and the California Newsroom filed a FOIA request for detailed budget information from the Eldorado National Forest, which remains pending.

Forest Service officials described the process of securing funding for specific projects as fluid and sometimes unpredictable.

“[The] budget is not a one-and-done thing,” said Erin Uloth, Acting Deputy Director of Strategic Planning, Budget, and Accountability for the agency. “It’s a very ongoing, constantly shifting, evolving thing.”

And since Congress routinely delays funding to the agency — doling out money on an interim basis as politicians in Washington clash over the federal budget — it’s not always clear how much will be available for individual national forests.

The Forest Service conceded as much in Trestle Project documents: “With several other large-scale projects occurring on the [Eldorado National] Forest, it is unlikely that funding for this project will be prioritized over funding for other projects.”

The Forest Service estimated timber sales would have covered about 80% of the $1.3 million cost for commercial tree thinning.

The real challenge is funding prescribed fires. Setting controlled burns under the Trestle Project would have cost about $3 million, according to project documents.

The bipartisan infrastructure law signed last year sets aside roughly $3 billion over five years for restoring ecosystems and fuels reduction. Chief Moore called it “a shot in the arm” for future forest management projects, but said more money is required to tackle the work needed across the Western U.S. The Inflation Reduction Act plans to provide $1.8 billion to the Forest Service for hazardous fuels reduction projects.

The money can’t come soon enough.

As former district ranger Nelson put it, the agency’s inability to get work done isn’t isolated to the Trestle Project and Grizzly Flats. Across the increasingly dry and fire-prone West, he said, the Forest Service has “over-promised and under-delivered on fire mitigation — work that could have changed fire behavior on these landscapes.”

Climate and Crews

Forest Service employees call them “Goldilocks days” — the brief window when weather, moisture levels, personnel demands and air quality all line up so prescribed burns can be done safely. Those days are becoming increasingly rare as hotter temperatures, severe drought and erratic weather patterns become facts of everyday life.

Rogers, the current Placerville district ranger, said his unit had a prescribed burn planned for spring of 2021, months before the Caldor Fire ignited.

“We had to cancel because conditions just weren’t quite right,” he said. “The historic drought conditions really cannot be overstated.”

Even Goldilocks days come with an asterisk. Concerns over escaped prescribed fires have also stymied plans. Less than 1% of prescribed burns get out of control, according to the Forest Service. But the ones that do can be devastating, creating PR nightmares and souring public support for this increasingly essential method of fuel reduction. Most recently, the Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire in New Mexico, which destroyed hundreds of homes, started after two Forest Service prescribed fires escaped.

Prescribed burns run amok can cause risk-aversion within the agency — from district rangers all the way to the top. Forest Service Chief Moore announced separate agency-wide prescribed burn suspensions this year and last year. Before Moore stepped in as chief, the Trump administration had suspended the practice in California in 2020.

Moore said this year’s pause only impacted “about 10%” of the agency’s planned prescribed burns, since most are done in the fall and early spring. But many prescribed-fire experts say the move is a dangerous step backward.

Then there’s the staffing problem. Setting and managing a prescribed fire requires a lot of personnel. Longer and more extreme fire seasons mean crews ping-pong from district to district and fire to fire, often remaining on the frontlines for weeks at a time with no break. That prevents them from managing prescribed burns and tackling other vegetation reduction projects in their home districts.

The Forest Service struggles to retain staff due to the untenable stress of working extreme fires and stagnant pay. President Biden vowed to improve firefighter wages, but getting money to people on the frontlines has been a slow process. After a time-consuming analysis of which regions struggled most with high vacancy rates, the federal government concluded “it is difficult to recruit or retain wildland firefighters in every geographic area.”

Lawmakers and labor unions are pushing the Forest Service to get the money out the door quickly.

“Employees are living in their trucks, vans, hammocks, or are ‘couch-surfing’ while working for the Forest Service,” wrote Randy Erwin, National President of the National Federation of Federal Employees, in a recent letter to the heads of the USDA and the Forest Service. “This is most often not by choice but out of necessity.”

‘We Did Our Job’

The day after Grizzly Flats burned, in August of 2021, former district ranger Duane Nelson had a call to make.

He had moved to southwestern Colorado after retiring from the Forest Service. He watched from afar as the Caldor Fire barreled through the Trestle Project area, leveled Grizzly Flats and then took off across the Eldorado National Forest.

“It was hugely frustrating,” he said. “My entire ranger district basically burned up.”

Frustration quickly gave way to anguish. Standing in a grocery store parking lot as shopping carts rattled by, Nelson dialed a close friend he hadn’t seen in years — Mark Almer.

“All I could say to him before I started crying was, ‘Mark, I’m so sorry,’” Nelson said. “Because I felt like we had not done all that we had hoped.”

The two men had worked for years toward the same goal — protecting Grizzly Flats — on opposite sides of the Forest Service boundary.

Nelson said he’s still processing the tragedy of the Caldor Fire.

“I’m not going to say I felt guilt,” he said. “We had done a lot of work trying to make that area as resilient to fire as possible. But what I did feel was remorse.”

Almer placed no blame on Nelson or the Forest Service for the devastation of the Caldor Fire. He gave them credit for at least drawing up a plan to protect the community, even if the Trestle Project fell years behind schedule.

“We’re neighbors, and neighbors take care of each other,” he said. “But sometimes, the best intentions don’t happen quickly.”

While the fire safe council’s efforts didn’t prevent the Caldor Fire from destroying most of Grizzly Flats, Almer views their work as a success.

“If everybody got out of here alive, then we did our job,” said Almer, noting that residents safely evacuated along routes cleared by the council. “People can rebuild — people can replace their stuff. But you can’t replace somebody’s life.”

Wara, the Stanford climate policy expert, marveled at the council’s dedication and handiwork after a recent trip to Grizzly Flats.

“I was driving those roads and said, how did no one get killed in this fire?” he recalled. “How is it that everyone got out? And the answer is, the community invested.”

Almer’s home survived a flurry of embers, some the size of baseballs. He spent 12 weeks in a Sacramento hotel with his wife and six cats, waiting to return to a barely recognizable neighborhood.

Others in the community, including residents who lost everything in the fire, are more critical of the Forest Service. In interviews, some laid blame at the agency’s feet.

“They did predict it, and they knew it was going to happen,” said Grant Ingram, a retired firefighter who now owns a fire-mapping business. The local fire district commissioned him to examine what happened before, during and after the Caldor Fire.

“If it’s predictable,” he added, “it’s preventable.”

Uncertain Future

Today, Grizzly Flats is stuck in a negotiation between devastation and recovery. One of the only green trees left in town isn’t a tree at all. It’s a rehabbed cell tower, covered with fake green boughs, across the street from where the Community Church once stood. The tower’s vibrant color contrasts with the remaining real trees, all of them burned like a forest of spent match sticks.

Up the road, a confused twister of scorched mail carts and collapsed P.O. boxes is all that’s left of the post office. An American flag flies above the rubble. In the parking lot, a couple of charred four-by-fours support a blackened crossbeam — the only remnants of the community bulletin board built by the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council over a decade ago.

While a few wood frames have gone up where homes once stood, it’s unclear how many Caldor Fire survivors will return to Grizzly Flats. Many are looking at homes elsewhere, ready for a new beginning.

Kathy Melvin, the longtime fire safe council member, lost her home. She recently purchased a new one in the suburbs of Sacramento. She’s holding onto her land in Grizzly Flats, maybe for her children to rebuild one day.

Victor Diaz, who escaped with his wife and six kids after Almer called and told him to evacuate, also lost his house. The entire family has been living in an RV since winter, next to where their new home is being built.

On a warm afternoon in late July, Almer stood on his fire-resilient deck and talked about a bright future for his town — even if it’s a distant one. He’s continuing to lead the fire safe council. And he’s optimistic that Grizzly Flats will eventually get a new community center; the nonprofit El Dorado Community Foundation has already raised at least a quarter million dollars toward the effort.

“The community will never look the way it did before the fire in our lifetime,” he said. “We know that the community will come back — how quickly and in what form, we’re not quite sure.”

Almer has already started the rebuilding process, fixing the things within his reach. He replaced the wood fence along his property that burned in the fire and the storage unit that holds cords of wood.

But some things he won’t replace. Pointing down at his deck, he called attention to several dark spots caused by scorching embers.

“We have spare pieces of decking,” he said. “I haven’t wanted to change it out, because it’s a reminder how fortunate we are.”

The California Newsroom is a collaboration of California public radio stations, NPR and CalMatters.