CAVANAUGH: I'm Maureen Cavanaugh. It's Tuesday, April 10th. Our top story on Midday Edition, a little over a year ago, San Diego launched project 25, an effort to get homes people who were the most frequent users of emergency services off the streets and into supportive housing. Today, the organizers of the effort are announcing the plan has been a success in saving money and changing lives. I'd hike to welcome my guests, Brian Maienschein is commissioner of plan to end chronic homelessness with the united way of San Diego County. Welcome back to the show. MAIENSCHEIN: Thanks, Maureen. Great to be back. CAVANAUGH: And James marsh is here too, a participant in project 25. Welcome to the show. MARSH: Thank you, glad to be here. CAVANAUGH: Now, Brian, you were on this show as project 25 was just in the planning stages. Can you tell us more about the concept? MAIENSCHEIN: Yeah, the concept was we identified the most expensive to taxpayers amongst the chronically homeless population. So these were individuals that took 50 or 60 emergency room trips a year, took the ambulance 60 time, were just very costly to taxpayers. And what we wanted to do by providing housing and services, see the savings that would result. In addition, we're obviously making a huge, positive impact in L lives. And we've shown that there's tremendous savings to taxpayers. CAVANAUGH: How did you actually go out and identify the people who might be participants in this project? MAIENSCHEIN: We put together a group of over 22 different organizations that signed on to participate, and we collected data from each of them. And we then compiled a list of the most expensive in San Diego County by name. And then we went out and did outreach on the street and were able to get them into the services and housing that was necessary to start saving the money. So it's been the result of a lot of work. But we're very pleased at the one year mark today to be able to come on here as -- you and I sat here together almost exactly one year ago and chatted about this. And now to look at where we are, it's very exciting. CAVANAUGH: And you were back about halfway into the first year and brought with you one of the participants, Stacy collingsworth. And he was -- he talked with us and he said he was doing great. How is he doing today? MAIENSCHEIN: She's still with the program. He's in housing, and actually he just started his first vocational training. So the goal is that one day he will cycle out of the program, he'll go off and get a job and resume his life and find the exact results we're looking for. So yeah, he's been another one of the success stories. CAVANAUGH: And today, we welcome James marsh, he's one of the participants in the program. How did you get chosen to be part of this project 25? MARSH: Well, I was one of the candidates that constantly uses the medical ambulances, the emergency rooms, as well as police departments. I ran up such a huge bill, it's just unbelievable. And I've been in there a year now. Of CAVANAUGH: Right. Now, how long were you living on the streets James? MARSH: Almost 12.5 years. CAVANAUGH: And what was it like to be living in one place again, having keys, keeping the place straightened up? MARSH: It was really unbelievable because I didn't think it would happen again because of my drinking problem. I never suspected that I would have the chance. And it's excellent. It's so exciting. CAVANAUGH: Brian, where are people like James actually being housed, and what services does project 25 provide? MAIENSCHEIN: We provide all the services. Project 25 is providing all the services. They're being housed in -- within the City of San Diego, through our partnership with the City of San Diego housing commission. James is downtown. But they can be anywhere within the City of San Diego boundaries. But James is really just kind of a typical success story. And just real quick, he had been talking about the amount of services he used. In 2010, he took 54 ambulance rides. This year, he's taken one. 51 emergency room visits versus one. Seven admissions to the hospital for 39 days versus zero. So just for James, it cost $479,000 versus this year, $6,000. CAVANAUGH: That is quite a drop in statistics. I was just about to ask you how you're measuring the success of project 25. Is this the way you're measuring it then, in terms of how frequently the participants used to use emergency services, how much they used to cost the city and the county, and now how much they're costing by being members of project 25? MAIENSCHEIN: We're doing it -- it's the first comprehensive data collection in the history of San Diego. And we're doing what the overall costs both before and during and then after the program. So we're able to, for example, in James's case, we're able to say that he cost $479,000 in 2010, he's cost $6,000. We have it down to the dollar. And we've seen a 77% reduction in emergency room visits, seventy-four% reduction in-patient medical stays, and then we're doing the data collection is being done by an independent origin, Point Loma Nazarene university, and they are reviewing the data, making sure it's academically correct, and it's an independent third party that's looking at the data, and putting its stamp of approval on it. So we look at it from an overall cost, what it costs taxpayers before and after, then we look at the reduction level in services too. CAVANAUGH: Right. And what is the overall cost of project 25? Is that factored in as well? MAIENSCHEIN: It is, it is. So what we found so far is the before the average project 25 participant in 2010 costs about $317,000 per individual to taxpayers. Their first year in the program, it's been about $95,000. And we expect that will go down over time. You're looking at $217,000, $222,000 savings on average per person. CAVANAUGH: Recently there was a series of reports in UT San Diego, that series was called healthcare 911. And if focused on frequent users of emergency services. Project 25 was the focus of one of those articles. Some of the challenges faced by the program were mentioned, for instance I'm wondering how many people fall out of the program because they can't adjust the way James has adjusted? MAIENSCHEIN: So far we haven't lost anybody. We have had a couple people exit for a short period of time, and then we got them back. So we haven't had anybody permanently leave. Having said that, it's entirely likely that we will lose a few people. But I do think the overall numbers are going to be so substantial, we're never going to bat a thousand on all of it, and that's never necessarily been the objective. What we're trying to do -- if we get to 100%, great. And so far so good, but to be honest with you, to be in the 80-90% would still be incredible. CAVANAUGH: What about -- and in fact project 25 is not exactly project 25 anymore. You have more people enrolled in the program than the 25 you originally were targeting. MAIENSCHEIN: That's right. It's funny because I came up with the name project 25 because to be candid, it was just a rough guess. I thought we could get about 25 in, and that would be what our band width would be. But since then, we've got 35 people enrolled in the program. We already printed the fliers so we can't rename it. I'm hoping that some day it will be project 50 and project 75 and project 100 because we'll continue to expand it. But we're excited to have 35 in, even in the initial stage. It's remarkable. CAVANAUGH: James, besides having a place now to live, what kind of services do you get true this program? MARSH: All my services. I definitely get all my medical, which I would have never even thought about trying to chase myself. They help me set goals that are abstainable, not something that's far-fetched. They give me inspiration, and they're there for me. You know, they're like my backbone to help me stand on my feet and not just give up. So they really push me along. CAVANAUGH: How has your health improved? MARSH: Substantially. Very well. It's not the way it was when I was on the street. I had no way to take care of it when I was on the street. CAVANAUGH: Do you interact with other people who are participants in project 25? MARSH: Oh, yes. I have, like, six alone in my building where I live and I interact with all of them. CAVANAUGH: And what -- do you get-together and talk about some of the problems that you might have in adjusting to living this way before being on the streets for so long? There must be a period of adjustment that you go through, right? MARSH: Oh, it is. No doubt. Yeah, I talked to a few of them about that. And I myself was in the same position because I only knew one way, and that was the street. So to have responsibilities was far fetched for me. But today, now that I know I can reach goals, and I have the opportunity to reach the goals, it's an inspiration. CAVANAUGH: Brian, what about people who do have a challenge and slip up? How do they reenter the program? MAIENSCHEIN: That's a part of the process. We understand that we're dealing with a very complicated population. And it can be difficult at times. So that has been built into the system in terms of the united way stepped up and funded case managers, which really helps to, you know, obviously the attempt is to avoid those slip-ups, and there's a lot of that that happens. Having said that, there's certainly some slip-ups, and that's when the case managers come in, and these are really dedicated people who are giving their life to make sure that this program works and succeeds, and so even when the slip-ups happen, at least so far as we discussed earlier, we haven't had anyone drop out of the program. CAVANAUGH: Now, this program is loosely modeled on similar programs across the country is that are part of the housing first program. Get people who are chronically homeless stabilized in a secure housing situation, attend to whatever medical needs they need, and so forth. And take it from there. Stabilize these men and women and see what other problems they my want to correct in their lives. Is that the idea in this program, or does someone have to remain clean and sober in order to stay in the housing? MAIENSCHEIN: Well, the reality is for people who are chronically homeless, the housing first component, in order to show the successes, that has to be the principle. Because in order to deal with whatever your problem is, the medical problem, whatever it is, being in housing, the statistics on that show you're much more successful and much more likely to deal with whatever your problem may be, if your housing situation is stabilized. If it's unstable, it makes it very, very difficult to solve whatever your problem may be. Of so yeah, that's a guiding premise behind the program. And as you see, when you do that, you see the savings, and then obviously you see the human success story, and somebody like James whose life -- his quality of life has gone up dramatically. CAVANAUGH: Right. Now, this project 25 is sponsored by a grant to San Diego County, administered by the united way. I believe that's correct. MAIENSCHEIN: It's a partnership between the City of San Diego housing commission, and the united way. CAVANAUGH: San Diego's permanent homeless shelter is scheduled to open later this year. MAIENSCHEIN: We're supportive of it, and it's something that I think is definitely a nice offshoot that's going on. But project 25 will continue independent of that. But it's something that I think is one more step in addressing the entire population. CAVANAUGH: In that UT San Diego series of articles, some administrators in other programs across the country talked with diminishing returns. Other cities have seen, you know, the amount of savings dramatic in the first few years of the program. And then the savings begin to diminish because that population is more stable. And they're not racking up these incredible emergency services bills. Eventually, the humanitarian aspect of helping at-risk people becomes a larger focus of these programs. Do you expect to see that happening in San Diego? MAIENSCHEIN: I do think it's both. I think it's both now, and it'll be both in the future. The reality is, the premise that I've always tried to focus on is there's an economic component to it. And that's kind of been the sea change, and looking at it economically. There's always been the reasons to look at it morally or ethically from a humanitarian standpoint. That will always be there. I think that exists today. I think it's both. I think there's certainly a compelling economic reason, and then there's compelling moral, ethical humanitarian reasons. That exists today, and I expect it will continue to exist in the future. For whatever reason, somebody wants to get involved or be supportive or look at it, wherever you come from on the continuum, I think it's a remarkable success story. CAVANAUGH: Right. James, you talked about this program helping you set realistic goals. Do you mind if I ask you what one of your goals is right now? MARSH: Sobriety. CAVANAUGH: And how far along are you on that? MARSH: I've got a month clean today. CAVANAUGH: Congratulations. MARSH: Thank you. CAVANAUGH: And do you see that being able to happen in the environment that you're in now? MARSH: Oh, yes, do completely. Because they gave the stability to want to change, they gave a reason to do something for myself as well as, you know, try to show other people that it can be done. CAVANAUGH: Brian, I'm wondering, how do you see this project evolving? You said you want it perhaps to be project 50, project 100. Is that really the goal? MAIENSCHEIN: It is. You look at -- we've taken right now we have 35 of the most difficult population to address. As we move through the list, it is going to start getting a little bit easier. And so yeah, absolutely, I'd love to see this become project 100, and eventually in a number of years, be able to move through the entire population. The other thing that happens too, as you take these high-end users out of the population, the dollar savings for people at the other end of the continuum go a lot farther. So you have very few people using a huge amount of money, and that money is freed up for people farther down the list, if you will. And so I would -- yeah, I absolutely think this can be shown in a data-driven way that it's successful. So I think a program that can prove that it saves money, saves lives, I think absolutely that's the type of program that through all levels of government, nonprofits should be continued. CAVANAUGH: Congratulations to both of you.

About a year ago, a new program started to target the 25 homeless people who cost San Diego the most money. Project 25 found those people who used emergency services the most and provided them with housing and other services.

Today, Brian Maienschein, commissioner of Plan to End Chronic Homelessness with the United Way of San Diego County, told KPBS so far the project has been a success.

“Before, the average Project 25 participant in 2010 cost about $317,000 per individual of taxpayers," he said. "Their first year in the program, it’s been about $95,000, and we expect that will go down over time. So you’re looking at $217,000, $222,000 savings on average per person.”

Maienschein said the project compiled its list of 25 people by partnering with 22 organizations "that literally went through and by name identified their most costly, to taxpayers, individuals."

"We compiled that list and we went out and got them into housing and services," he said.

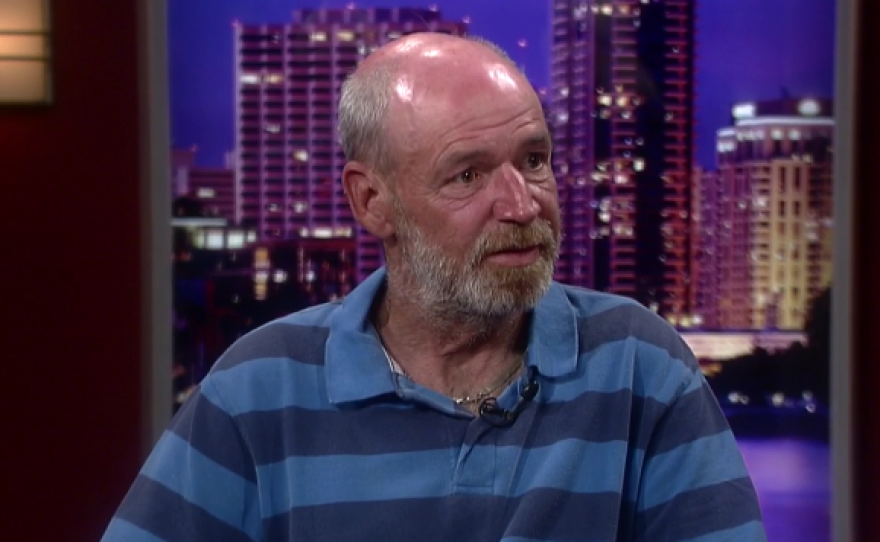

James Marsh, one of the Project 25 participants, took 54 ambulance rides in 2010. This year, he has taken one. In 2010, he made 51 emergency room visits. This year, he made one. That has dropped his cost to the city from $479,000 to $6,000.

Marsh said beyond those improvements to his health, the feeling of holding keys to his own apartment has been unbelievable.

"I didn’t think it would happen again," he said. "Because of my drinking problem, I never suspected that I would have another chance. And it’s excellent. It’s so exciting.”

“I cried," he added. "I can't even remember the last time I had my own key to my own place. And when I walked in and looked at it, it was like, this is mine, this is my home, I'm not in a bush, I'm not under a park bench somewhere."

Marsh said he remembers "clear as day" the first time someone from Project 25 approached him.

"I happened to be incarcerated, and I was waiting to go to a program, and Project 25 came before the program did and explained to me what it was about and if I would be interested," he said.

He said they told him "we're going to give you a chance to start over, we're going to show you that you are somebody and that you can believe in yourself."

Project 25 ended up helping 35 people - 10 more than expected - and found permanent housing for 31 of them. The project has a three-year commitment to continue operating, and Maienschein said they hope to continue beyond that.