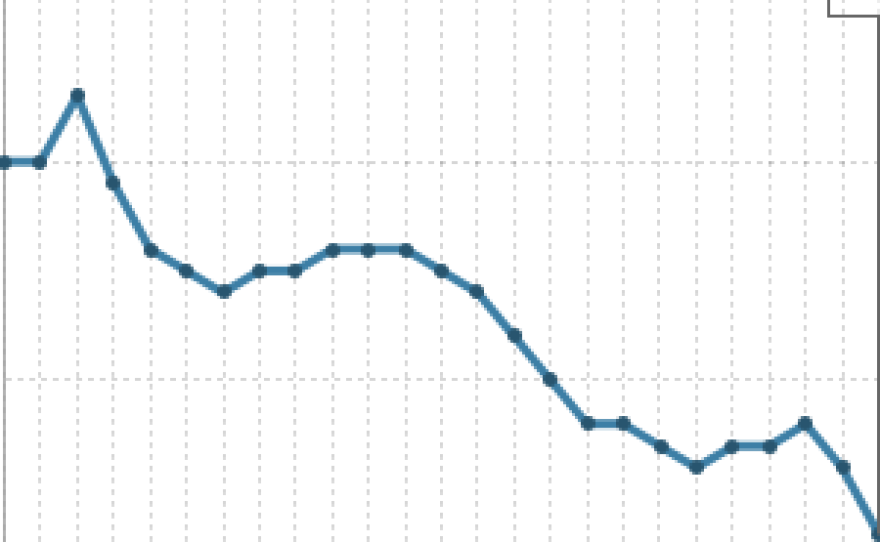

The nation's unemployment rate rose to 9.8 percent in November after holding steady for months, defying analysts' expectations and raising concern that the economic recovery is losing steam.

The rate was up from 9.6 percent in October, where it had held for three straight months. The rate now has topped 9 percent for 19 months –- the longest stretch on records going back to 1948.

The unexpectedly disappointing numbers also added fodder for the partisan debate on Capitol Hill over extending both the Bush-era tax cuts and jobless benefits for the long-term unemployed. Those benefits expired for millions of Americans at midnight Tuesday after Democrats and Republicans in Congress failed to agree on how they should be further extended.

Employers added a net total of only 39,000 jobs last month, a sharp decline from the 172,000 created in October, the Labor Department said Friday. The number was also far below the 150,000 or so new jobs most economists had expected –- a figure that would have kept the unemployment rate steady.

White House economic adviser Austan Goolsbee called the unemployment rate "unacceptably high," adding that "today's numbers underscore the importance of extending expiring tax cuts for the middle class and unemployment insurance for those Americans who have lost their jobs."

Pointing to the figures, House speaker-elect John Boehner (R-OH) criticized Democrats' efforts to stimulate the economy. He called on Congress to "do the right thing and stop all the tax hikes."

Democrats want to extend the tax cuts only for income up to $250,000. Republican leaders in the Senate have vowed to block all legislation unless the tax cuts are extended for all income levels.

"Unfortunately, Democratic leaders continue to insist on wasting time with meaningless votes as they try to make it as difficult as possible to stop their job-killing tax hike," Boehner said in a statement.

Gloomy Figures

Stephen Bronars, a senior economist at Welch Consulting, called Friday's report "disappointing, to say the least."

Bronars said private-sector employment has hovered around 1 percent for the past year, and "that's just not enough to pull us out of this deep recession."

Private employers added 50,000 jobs, down significantly from the 160,000 private-sector jobs created in October and the smallest gain since January. The public sector -- mostly local governments -- eliminated 11,000 positions.

"Job growth is not strong enough to take up all the new entries in the job market," economist Hugh Johnson told NPR. "It's a very disappointing report almost across the board."

Johnson said "the economy is recovering, but it's recovering at a very, very slow pace."

Weakness hit most sectors of the economy, including retailers, factories, construction companies, financial firms and the government. In all, 15.1 million people were out of work in November.

The few bright spots included health care, which added 19,000 jobs, and the mining sector, adding 6,000 jobs in November.

The number of "underemployed" –- defined as people working part-time who would prefer full-time jobs and those who have given up looking for work -- was 17 percent, the same as October. Still, the figure remains close to a record high set last year.

About 7 million to 8 million private-sector jobs were lost in the 2007-2009 period, Bronars said.

"We got about a million of them back, but there are more and more people entering the labor force," he told NPR.

A record 1.3 million "discouraged" workers -– people who have given up looking -- were counted in the November numbers.

Last month, retailers slashed 28,100 jobs, while factories cut 13,000, financial firms shed 9,000 and construction companies trimmed 5,000.

The economy needs to add at least 120,000 jobs to hold the unemployment rate in check but needs to add 300,000 new jobs a month to bring the rate down.

"Certainly, we had gotten our hopes up after a broad sweep of economic data over the last month or so, but it's not reasonable to expect things to move in a straight line," said Alan Levenson, chief economist with T. Rowe Price in Baltimore.

"If the goal is to get below 9 percent, that probably won't happen before the middle of next year," he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))