When Steve Jobs stepped down from his position as CEO of Apple yesterday, he handed the reins immediately to chief operating officer Tim Cook, who has had such a significant hand in day-to-day operations that many expect that Apple won't immediately suffer much in the way of effects on either its ability to turn out beloved products or its business position.

But there is, too, a cultural Apple, for lack of a better term: the ground staked out not solely by its profits and its technical accomplishments, but by its fascination with design, its laid-back advertising that echoes the spareness of its products, and its cultivation of fans who — like All Songs Considered host Bob Boilen — feel about the departure of Jobs the way they felt about the Beatles breaking up. This "cultural Apple" is not Apple as a manufacturer or a corporation; it is Apple as something akin to an artist. A participant in culture, rather than just in the marketplace.

The relationship between Apple and its aficionados has always borne little resemblance to the relationships consumers have with most other giant companies, tech companies, or even brilliantly marketed companies. To see congruence, for instance, between Apple fans and Microsoft users based on the constant back-and-forth that makes fights between them so pointless and eternal is to misunderstand how those discussions work. People love Apple; at best, they appreciate Microsoft (and, more to the point, grow weary of those people who love Apple). What you see is not "Apple is brilliant," "No, Microsoft is brilliant." What you see is, "Apple is brilliant." "Oh, would you shut up already." These discussions, for those who choose to spend time on them, are often about a binary sense of Apple: Apple Yes, and Apple No. That's the definition of the argument, and that's the definition of dominating the part of the culture in which you exist.

The cultural Apple has contributed enormously to its business and technical successes. Google may have been the company that has popularized the slogan "Don't be evil," but Apple is the company that used its cultural position to persuade its users most effectively that it wasn't evil. That's why Apple can refuse to implement an element as common as Flash and can straightforwardly say, in effect, "We're keeping this from you for your own good, and eventually, you'll be better off." And it works. Not on everyone, but on enough. There are very few companies that could willfully limit the usefulness of a product and trust that they've built enough capital with customers that reduced functionality will be seen, as it is by many iPod/iPad/iPhone users, as both the right business choice and a blow in favor of the consumer in pushing toward a better piece of technology.

That capital, despite the bonds that tend to draw Apple people to each other, isn't strictly social capital, and it's not strictly old-school customer confidence; it is a business-cultural hybrid that's enormously difficult to achieve. Mark Zuckerberg can't convince Facebook users that Facebook is looking out for their privacy; Bill Gates can't convince Windows users that Microsoft is pursuing reliability. But Steve Jobs can convince enough Apple users of the fundamentally benevolent position of the company relative to its customers that Apple's efforts to get music devotees into Apple-Apple-Apple systems — in which they sync an iPod to a MacBook to move iTunes music — don't plague Apple with the same accusations of anti-consumer behavior that would strike most other sellers who tried the same thing.

People frustrated with those they consider Apple fetishists consider that level of devotion to be irrational cool-kid posturing and an iPod no different from a very expensive trucker hat. But people who have used Apple products for years will tell you it's not cachet, but well-earned trust, and that its rarity doesn't demonstrate that Apple is a social fluke, but that it's an incredibly competent organization with a string of successes no one else can match.

It really doesn't matter whether that cultural capital has been earned or ginned up or some of each; the point now is that it exists, and Steve Jobs is a big part of it.

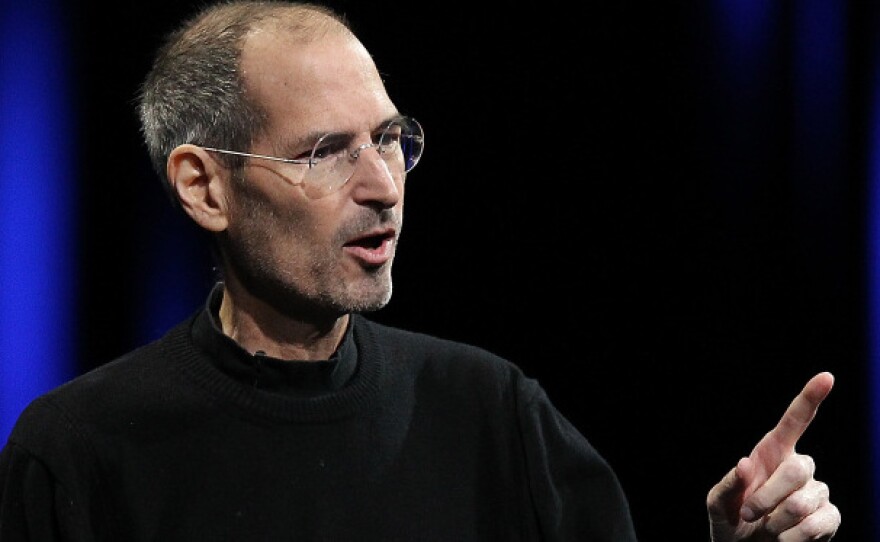

He's the one with the uniform who goes on stage at presentations that would be more at home at Comic-Con or halftime at the Super Bowl than at a trade show. Apple product introductions, most of which he has delivered in recent years, are treated like the Oscars — live-tweeted, fussed over, front-paged, written up for their great "moments" almost as much as for their content.

Jobs in that black mock turtleneck and jeans, casually seated in a chair, telling you how great the future is going to be: that image represents something very valuable to Apple people. They believe, having seen it with the iPod and the iPhone and the iPad, that when he tells them something good is going to happen, he's right. Those appearances are, for many, like getting a new medication from a doctor. They don't hear him say, "Here's something you should buy; please let me separate you from your money." They hear something more like, "I have great news — we've fixed the problem." Apple has untethered itself from the enormous skepticism and distrust that plagues tech culture to such a degree that people actually believe it fixes problems.

You might not have known you had the problem, of course, but hearing Steve Jobs explain the solution can make you feel like if you didn't have the problem yesterday, you will certainly have it tomorrow.

People don't line up outside Apple stores to be the first to get Apple products in their hands solely because of how well those products will work. They wait in those lines because they are believers. And you can't really have believers without someone to believe, and that person has been Steve Jobs. Being ousted from Apple and returning to lead it to massive successes, being affiliated with the fairy dust of Pixar, and the way he's discussed (and not discussed) his battle with cancer have all been part of the fundamental sense that he knows something, that he's solid, that he's not just some guy selling something, whether that's the case or not.

Whether Jobs will continue to do those public appearances is unclear at this point. If he doesn't, Apple will need Cook or someone else to carry the cultural side of the company, to be the same kind of soothing, persuasive presence who can give Apple the face it needs in order to maintain the cultural positioning that, in the ten years since the introduction of the iPod, has become something qualitatively unique. Right now, Apple's biggest advantage — over Microsoft, over Google, over Amazon, over everybody — is its Apple-ness. You can believe they've earned that, or you can believe they've snookered people into it, but they have it, and they make use of it, and in a rational world, it would appear on any list of their assets. Quite possibly at the top.

Apple isn't going to stop making iPads or close up shop because Steve Jobs is leaving. But they may be showing a different face to the public and speaking to the public in a different voice. And if that happens, the cultural Apple may change substantially more than the technical Apple or the business Apple.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))