In a windowless laboratory in downtown Baltimore, some tiny, translucent fish larvae are swimming about in glass-walled tanks.

They are infant bluefin tuna. Scientists in this laboratory are trying to grasp what they call the holy grail of aquaculture: raising this powerful fish, so prized by sushi lovers, entirely in captivity. But the effort is fraught with challenges.

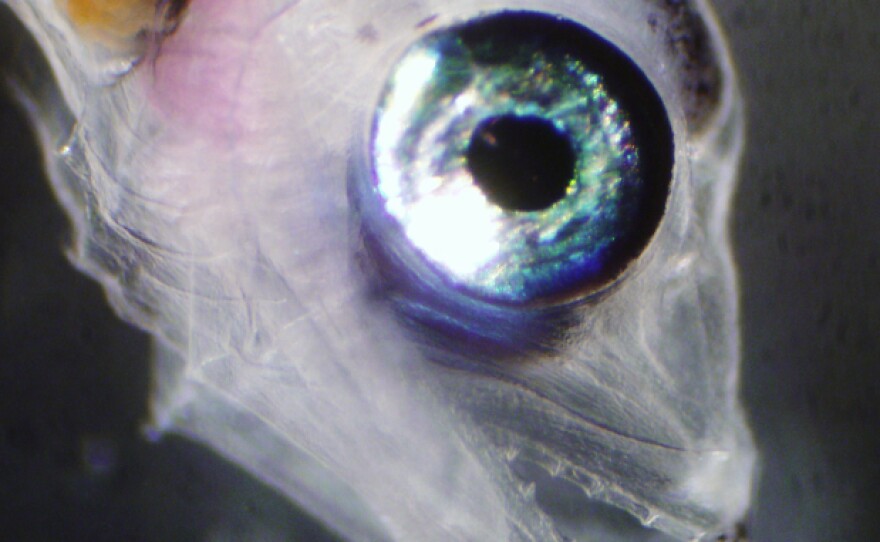

When I visited, I couldn't see the larvae at first. They look incredibly fragile and helpless, just drifting in the tanks' water currents. But they're already gobbling up microscopic marine animals, which in turn are living on algae.

"It's amazing. We cannot stop looking at them! We are here around the clock and we are looking at them, because it is so beautiful," says Yonathan Zohar, the scientist in charge of this project.

It's beautiful to Zohar because it's so rare. Scientists are trying to raise bluefin tuna completely in captivity in only a few places around the world. Laboratories in Japan have led the effort. This experiment, at the University of Maryland Baltimore County's Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology, is the first successful attempt in North America. It's also the first in the world to do it with Atlantic bluefin tuna.

Scientists still have a long way to go to succeed. Most of the larvae have died, but hundreds have now survived for 10 days, "and we are counting every day," says Zohar. "We want to be at 25 to 30 days. This is the bottleneck. The bottleneck is the first three to four weeks."

If they make it that far, they'll be juvenile fish and much more sturdy. Then, they'll mainly need lots to eat.

Fully grown, the bluefin tuna is a tiger of the ocean: powerful and voracious, its flesh in high demand for sushi all around the world.

Journalist Paul Greenberg wrote about bluefin tuna in his book Four Fish. If you're an angler, he says, catching one is an experience you don't forget.

"When they come onboard, it's like raw energy coming onto the boat. Their tail will [beat] like an outboard motor, just blazing with power and energy," he says.

The fish can grow to 1,000 pounds. They can swim up to 45 miles per hour and cross entire oceans.

They're also valuable. Demand for tuna has grown, especially in Japan, where people sometimes pay fantastic prices for the fish.

That demand has led to overfishing, and wild populations of tuna now are declining.

That's why scientists like Zohar are trying to invent a new way to supply the world's demand. They're trying to invent bluefin tuna farming.

"The vision is to have huge tanks, land-based, in a facility like what you see here, having bluefin tuna that are spawning year-round, on demand, producing millions of eggs," he says.

Those eggs would hatch and grow into a plentiful supply of tuna.

That brings us back to these precious larvae. Before there can be aquaculture, large quantities of these larvae have to survive. Here in the laboratory, the scientists are tinkering with lots of things — the lights above the tanks, the concentration of algae and water currents — to keep the fragile larvae from sinking toward the bottom of the tank.

"They tend to go down," explains Zohar. "They have a heavy head. They go head down and tail up. If they hit their head on the bottom they are gone. They are not going to survive."

Enough are surviving, at the moment, that Zohar thinks they're getting close to overcoming this obstacle, too.

But that still leaves a final hurdle. The scientists will need to figure out how to satisfy the tuna's amazing appetite without causing even more damage to the environment.

A tuna's natural diet consists of other fish. Lots of other fish. Right now, there are tuna "ranches" that capture young tuna in the ocean and then fatten them up in big net-pens. According to Greenberg, those ranches feed their tuna about 15 pounds of fish such as sardines or mackerel for each additional pound of tuna that can be sold to consumers. That kind of tuna production is environmentally costly.

Zohar thinks that it will be possible to reduce this ratio or even create tuna feed that doesn't rely heavily on other fish as an ingredient.

But Greenberg says the basic fact that they eat so much makes him wonder whether tuna farming is really the right way to go. It increases the population of a predator species that demands lots of food itself.

"Why would you domesticate a tiger when you could domesticate a cow," he asks — or, even better, a chicken, which converts just 2 pounds of vegetarian feed into a pound of meat.

If farmed tuna really can reduce the demand for tuna caught in the wild, it would be worth doing. But it might do more good, he says, to eat a little lower on the marine food chain. We could eat more mussels or sardines. It would let more tuna roam free.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/