When the East German government erected the Berlin Wall in 1961, it underestimated just how far some were willing to go to make it out of the communist country.

And perhaps no one went to greater lengths than the Berlin Wall "mole," Hasso Herschel, who is credited with helping more than 1,000 East Germans escape to the West from 1962 to 1972, inspiring the 2001 film The Tunnel.

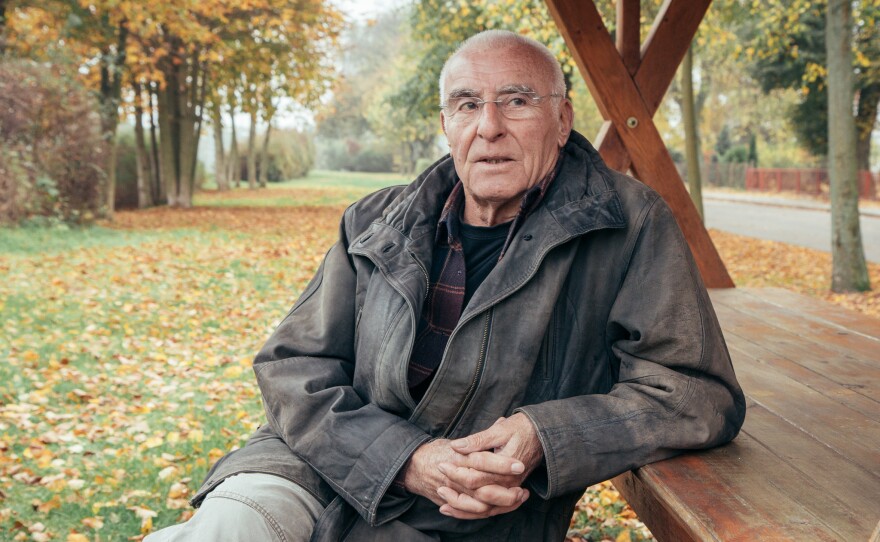

On the 25th anniversary of the wall's demise, I caught up with Herschel, who is now 79 and lives on a farm north of Berlin, spending his days shoveling hay and herding sheep.

The first escape that Herschel engineered from East to West was his own.

Born in Dresden in 1935, Herschel was a member of the Hitler Youth as a child and then became a champion swimmer as a teenager in East Germany, formally known as the German Democratic Republic.

But by his late teens, he was in constant trouble with East German authorities, including a four-and-a-half-year stint in a labor camp for "economic crimes" related to selling a typewriter, binoculars and a camera in the West.

"The final straw for me was when the government began turning guns on their own citizens. By then, I knew it was time to go," Herschel says.

Using a forged Swiss passport from a West Berlin student, Herschel successfully crossed the border to the West on Oct. 21, 1961, just two months after the Berlin Wall was built.

Before fleeing, he had made a pact with family and friends that the first one out would help the others flee. So in May 1962, he teamed up with two Italians, Domenico Sesta and Luigi Spina, and began digging Tunnel 29, a 150-yard-long operation leading into an East Berlin basement on Schönholzer Strasse in West Berlin.

Desperately needing money for materials, they approached the U.S. television network NBC and proposed the filming of a real escape. To the amazement of Herschel and his partners, NBC agreed and paid them a hefty advance to begin construction.

On Sept. 14 and 15, 1962, they brought 29 people to the West, including Herschel's sister, Anita, her husband, Hannes, and their 1-year-old baby daughter, Astrid. One woman was so eager to arrive in the West in style that she clambered through the muddy tunnel in a Dior dress.

"Some were completely pale when they entered the West, collapsing to the floor and crying, "Finally! After four years of waiting!" Herschel says.

And it was captured on film.

After this initial success, Herschel was bombarded with pleas from people asking him to help their friends and family flee. Not all his tunnel escape missions went as smoothly as the first, though.

In 1963, East German police staked out the tunnel from the ground above using detection devices, and Herschel had to abandon the operation.

Herschel then became involved in long distance escape assistance from Hungary to Austria in hidden car compartments through the support of diplomats, charging escapees up to $8,000.

Herschel insists it was not about the money at the time. He did became a businessman in later years, owning several restaurants, bars and clubs in West Berlin until he went bankrupt.

When the Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9, 1989, Herschel was so overjoyed that he opened the doors of his West Berlin club that Thursday so everyone could celebrate.

"I never believed the wall would ever fall," he says. "We all started to believe in world peace that day. Apart from the birth of my daughters and my prison release, that was the best day of my life."

He says the bustling metropolis of Berlin today is worlds apart from the divided city it once was.

"When you walk around Berlin nowadays, you can't really notice the difference between East and West anymore, let alone see where the wall once was," he says. "The city's 'scar' has disappeared completely. Even our head of government, Angela Merkel, is from the GDR."

In recent years, he worked at Berliner Unterwelten, or Berlin's Underworld, giving talks on how his subterranean escape routes worked. He grew tired of retelling his story, but he still gets attention for his deeds.

"My sister always tells me, 'Thanks to you, I could live my life the way I wanted to.' I also get lots of calls from people saying, 'Forty years ago today, you helped my wife flee. I'm forever grateful,' " he says.

"It's not like I wake up in the morning and think, 'I'm such a hero,' " he says. But he does appreciate the kind words.

"When so many people say you've changed their lives in a positive way, perhaps it's a kind of gratitude and recognition that doctors experience. Someone even once called me up and said, 'Yesterday we had a baby and we named him Hasso.'"

Emily Wasik is a freelance journalist based in Berlin. You can follow her @EmilieWasik.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.