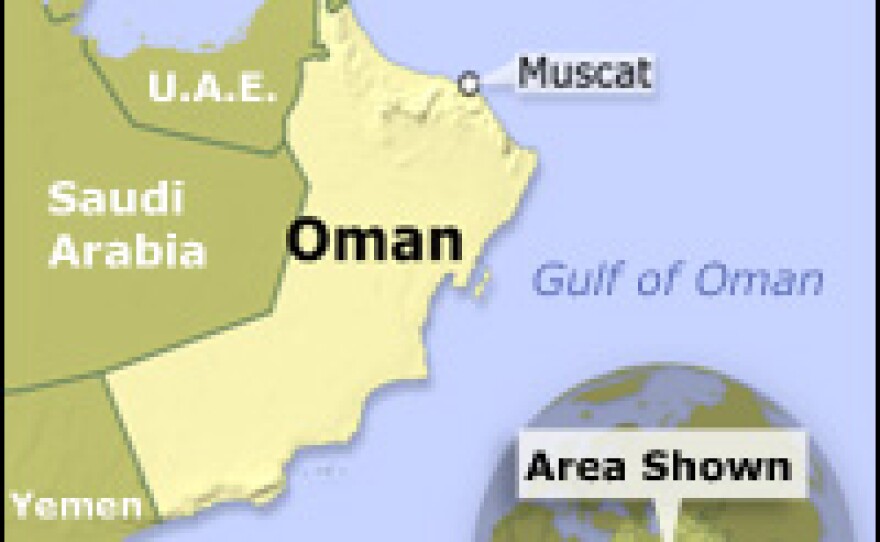

It's a festive time in Oman, the sleepy sultanate on the edge of the Persian Gulf. The national day is Nov. 18, marking Oman's liberation from Portugese colonization, and the capital Muscat is bedecked with banners, scarves and flags. The spicy-sweet smell of frankincense is everywhere, as are images of Oman's absolute monarch for the past 44 years, Sultan Qaboos bin Said.

Sultan Qaboos, as he's universally known here, is still dominating the national conversation several days after his first public appearance in months. He addressed the nation via television from Germany where he's undergoing treatment for an undisclosed medical condition.

Appearing frail, the slender, bearded ruler said he would have to miss the national celebration – which falls on his 74th birthday – to continue his treatment.

Sultan Ahmed al-Ruhmi, a 32-year-old Omani from a village some 90 miles outside of the capital, says the sultan's message was reassuring, but his long illness has forced people to consider the prospects for an Oman without Qaboos.

Many, like Ruhmi, have never known any other ruler, and with the Middle East in turmoil people want Qaboos back in Muscat, steering a peaceful, neutral course through choppy waters.

"Omanis, they are very much aware of what is happening in the region, an ideological war," Ruhmi says. "Omanis are very eager to welcome the Sultan again and get the benefits of his wisdom."

Embracing The Wider World

Qaboos came to power in 1970, overthrowing his father in a palace coup. Where his father was inward-looking and reclusive, the young sultan opened up the economy and improved living standards.

Business Today magazine says Qaboos has increased Oman's gross domestic product from $256 million in 1970 to around $80 billion last year.

Personally, he remains something of an enigma, even to Omanis. A brief marriage left no children, and while he hasn't always been shy about spending his nation's relatively modest oil and gas wealth – his yacht is ranked as one of the world's biggest — many Omanis see him as a devoted, paternal figure.

He holds virtually all the important titles in the Omani government – foreign minister, defense minister, finance minister, governor of the central bank.

While expanding the economy, he has also managed to keep the peace, ending a rebellion in the 1970s and resolving a brief period of unrest during the Arab Spring movements in 2011.

In keeping with Oman's original take on politics and governing, Sultan Qaboos has devised a distinctive succession process: in the event of his demise, a council made up of his family members will have three days to decide on the next sultan.

If the council can't agree, Qaboos has reportedly left two copies of a letter naming his preferred successor. For years, what little speculation there is has focused on three of Qaboos's cousins: Assad, Shihab and Haitham bin Tarek bin Taimur al Said.

Bridging The Gulf's Sectarian Divide

No other Persian Gulf state manages to cross the Sunni-Shiite sectarian frontiers the way Oman does, and there are a number of reasons for that.

Oman has a long and rich history of maritime trade, and like many historic ports of call, has attracted a diverse population. In addition, most Omanis are neither Sunnis nor Shiites, but Ibadis – an ancient branch of Islam that technically predates either of the two better-known sects.

Qaboos has managed to keep good relations with both his powerful Sunni neighbor Saudi Arabia and Shiite powerhouse Iran, just up the Strait of Hormuz.

Unlike the Saudis, Oman does not fund Sunni opposition fighters in Syria or other hotspots. And unlike Iran's leaders, Qaboos does not back proxy Shiite militias such as Hezbollah in Lebanon. As it has down the centuries, Oman has sought smooth relations and commercial trade both in the Gulf and beyond.

"Qaboos' great strength has been to play the outlier," says Simon Henderson of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. "He's been friendly to the United States and indeed to Britain, and he's also been friendly to Iran. And he's played this to his advantage in terms of diplomatic contacts."

The most recent example was on display last week as Oman hosted negotiations between Iran and several world powers over Iran's nuclear program. Oman hosted secret talks between U.S. and Iranian officials in 2012, which launched the current process.

Ken Pollack, a former CIA Persian Gulf analyst and National Security Council staffer now at the Brookings Institution, says those back-channel talks laid the foundation for the landmark interim nuclear accord that was announced in Geneva in November 2013.

"Obviously it's too soon to say whether those negotiations are going to turn out to be a success," says Pollack. "But that was nevertheless a very important starting point for making the progress even that we've made so far."

Oman also has a financial stake in Iran getting out from under international sanctions and rejoining the global economy – it shares a gas field with the Islamic Republic. But Pollack doesn't think economics is Oman's primary motivation.

"This has been going on for decades, where the Omanis have been trying to patch up the relationship between the Iranians and the West," he says, "mostly because of their political and security fears that if there were a war of some kind that they would literally be caught in the middle of the shooting."

Bloodshed is on the rise in Yeman, another of Oman's neighbors, and with daily reports of chaos emanating from Iraq and Syria, the potential consequences of the collapse of the Iran nuclear talks are casting a troubling shadow on this peaceful corner of the Gulf.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.