It's been less than a year since a domestic violence scandal erupted in the National Football League. The infamous Ray Rice video from last September and the league's mishandling of the case plunged the NFL into an unprecedented crisis.

It also spurred the league into action after years of doing little or nothing about the problem of domestic violence. The problem continues and so do the efforts to fight it.

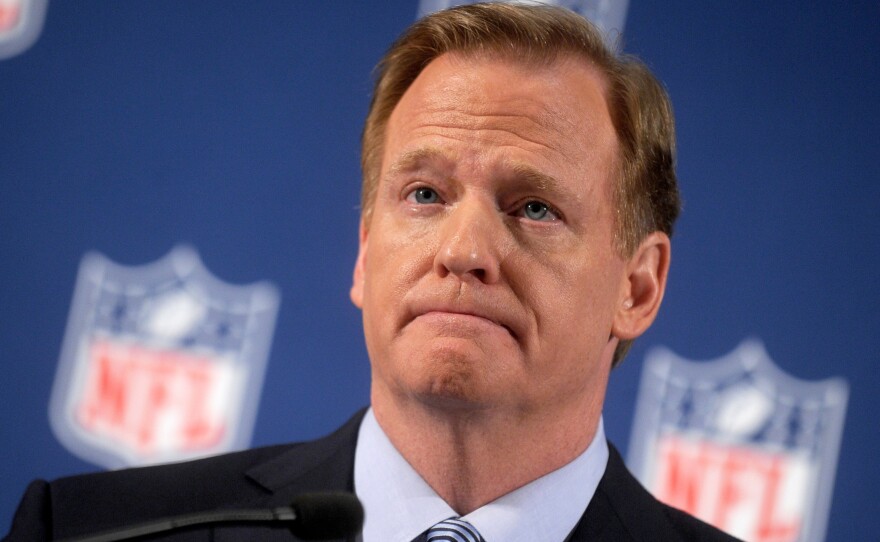

Rewind to last September when NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell publicly repented. "I got it wrong in the handling of the Ray Rice matter, and I'm sorry for that," he said.

Anna Isaacson already was working to fulfill Goodell's promise to "do whatever is necessary" to get it right. "And I can really remember sending an email around saying here's what the solution is going to be, here's how we're going to move this forward," she says.

Isaacson's part of the solution was education. As the newly appointed senior VP of social responsibility, she had the job of educating everyone employed by the league and teams about domestic violence. Last year, Isaacson oversaw a program of live training sessions and a webinar that included the story of Pittsburgh Steelers player William Gay, whose mom was killed by his stepfather.

"She was shot several times in the back and survived all the way to the hospital until she couldn't fight anymore, and eventually dying. And when I lost my mom at 7, you know I just thought the world was over," Gay says in a video.

Despite the emotional vignettes, some players reportedly thought the sessions didn't work. Media reports cited off-the-record criticisms by players saying they felt alienated, lumped together as perpetrators. In fact, the arrest rate for domestic violence is lower among NFL players than non-football playing men in the same age group.

But an NFL arrest database shows seven players have been arrested in relation to domestic violence since the Rice video emerged. It underscores the need to continue education. New sessions are underway now in training camps.

Isaacson says this second round will answer some of the criticism. It's much more discussion-based rather than speaking at players, and, she says, there's more opportunity to engage players by highlighting how they can help as active bystanders.

"You can take action if you see it and how to recognize the signs and the symptoms," she says.

Another part of the league's anti-domestic violence strategy involves investigations. Lisa Friel was hired post-Ray Rice to head up this effort after working 28 years in the Manhattan DA's office — 25 of them in the sex crimes unit.

She says the NFL, like all sports leagues in this country, deferred almost completely to law enforcement in alleged criminal matters involving players. And if the criminal justice system, which Friel says certainly isn't perfect, didn't punish players, leagues usually wouldn't either.

Now the NFL has started its own investigations, although it lacks subpoena power Friel had in her previous job. She says it's a major step forward.

"Anything that you've read about in the newspapers where there was an allegation, we've immediately begun an investigation and many things that you wouldn't have read about because even if we find out from other sources, somebody could call us directly who feels they've been victimized, and we would start looking into that," she says.

The NFL has looked outside its world as well. It made a five-year, $25 million commitment to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Thanks to that money the hotline has 100 more full-time employees and has served nearly 52,000 more people than last year.

Of course there's always more to do. Anti-domestic violence advocates stress the importance of early intervention and how the NFL, with its immense popularity, could have programs solely devoted to character education of young athletes even in elementary and middle schools. Currently, the league does not.

Nearly a year after he was suspended indefinitely, Rice is reinstated and hoping to play football again. In a recent ESPN interview, Rice recounted the moment that changed his life and the course of the NFL: the punch, dragging his limp fiancée out of an elevator and not helping her up.

"I should've never put my hands on her, number one, but to leave her there, to just treat her like nothing, was the worst thing I've ever could've done," he said.

If some team takes a chance on Rice, he'd be coming back to a league that, according to Friel, now has a no-tolerance policy on domestic violence. It's not zero tolerance: a first offense warrants a six-game suspension; the second offense, banishment.

Those who excoriated the NFL and Goodell last year still question the commissioner's leadership and whether the league's anti-domestic violence efforts simply are PR. Those inside the league say those efforts already are bearing fruit but that longevity is the best counter to critics. Isaacson — one of those working to help move the league forward — likes to remind herself to keep going.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.