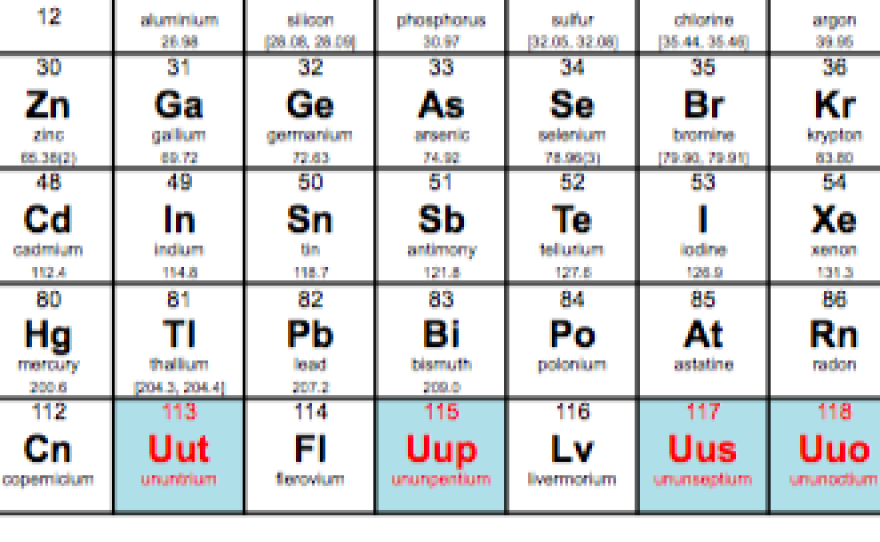

For now, they're known by working names, like ununseptium and ununtrium — two of the four new chemical elements whose discovery has been officially verified. The elements with atomic numbers 113, 115, 117 and 118 will get permanent names soon, according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

With the discoveries now confirmed, "The 7th period of the periodic table of elements is complete," according to the IUPAC. The additions come nearly five years after elements 114 (flerovium, or Fl) and element 116 (livermorium or Lv) were added to the table.

The elements were discovered in recent years by researchers in Japan, Russia and the United States. Element 113 was discovered by a group at the Riken Institute, which calls it "the first element on the periodic table found in Asia."

Three other elements were discovered by a collaborative effort among the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. That collaboration has now discovered six new elements, including two that also involved the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

Classified as "superheavy" — the designation given to elements with more than 104 protons — the new elements were created by using particle accelerators to shoot beams of nuclei at other, heavier, target nuclei.

The new elements' existence was confirmed by further experiments that reproduced them — however briefly. Element 113, for instance, exists for less than a thousandth of a second.

"A particular difficulty in establishing these new elements is that they decay into hitherto unknown isotopes of slightly lighter elements that also need to be unequivocally identified," said Paul Karol, chair of the IUPAC's Joint Working Party, announcing the new elements. The working group includes members of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics.

The elements' temporary names stem from their spot on the periodic table — for instance, ununseptium has 117 protons. Each of the discovering teams have now been asked to submit names for the new elements.

With the additions, the bottom of the periodic table now looks like a bit like a completed crossword puzzle — and that led us to get in touch with Karol to ask about the next row, the eighth period.

"There are a couple of laboratories that have already taken shots at making elements 119 and 120 but with no evidence yet of success," he said in an email. "The eighth period should be very interesting because relativistic effects on electrons become significant and difficult to pinpoint. It is in the electron behavior, perhaps better called electron psychology, that the chemical behavior is embodied."

Karol says that researchers will continue seeking "the alleged but highly probable 'island of stability' at or near element 120 or perhaps 126," where elements might be found to exist list enough to study their chemistry.

International guidelines for choosing a name say that new elements "can be named after a mythological concept, a mineral, a place or country, a property or a scientist," according to the IUPAC.

In 2013, Swedish scientists confirmed the existence of the Russian-discovered ununpentium (atomic number 115). As the Two-Way described it, the element was produced by "shooting a beam of calcium, which has 20 protons, into a thin film of americium, which has 95 protons. For less than a second, the new element had 115 protons."

While you're not likely to run into the new elements anytime soon, they're not the only ones with have short existences. Take, for instance, francium (atomic number 87) and astatine (atomic number 85).

As Sam Kean, author of a book about the periodic table called The Disappearing Spoon, wrote of those elements:

"If you had a million atoms of the longest-lived type of astatine, half of them would disintegrate in 400 minutes. A similar sample of francium would hang on for 20 minutes. Francium is so fragile, it's basically useless."

As for why scientists keep pursuing new and heavier elements, the answer, at least in part, is that they're hoping to eventually find an element — or a series of elements — that are both stable and useful in practical applications. And along the way, they're learning more and more about how atoms are held together.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.