A series of medical images published Tuesday offer the most complete picture, so far, of how the Zika virus can damage the brain of a fetus.

"The images show the worst brain infections that doctors will ever see," says Dr. Deborah Levine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who contributed to the study. "Zika is such a severe infection [in fetuses]. Most doctors will have never seen brains like this before."

The images — published in the journal Radiology — are part of a special report put together by neurologists in Boston and doctors in northeastern Brazil who care for babies with Zika infections.

"Our goal is to illustrate for heath care professionals around the world what they could expect to see with a Zika infection during pregnancy," Levine says.

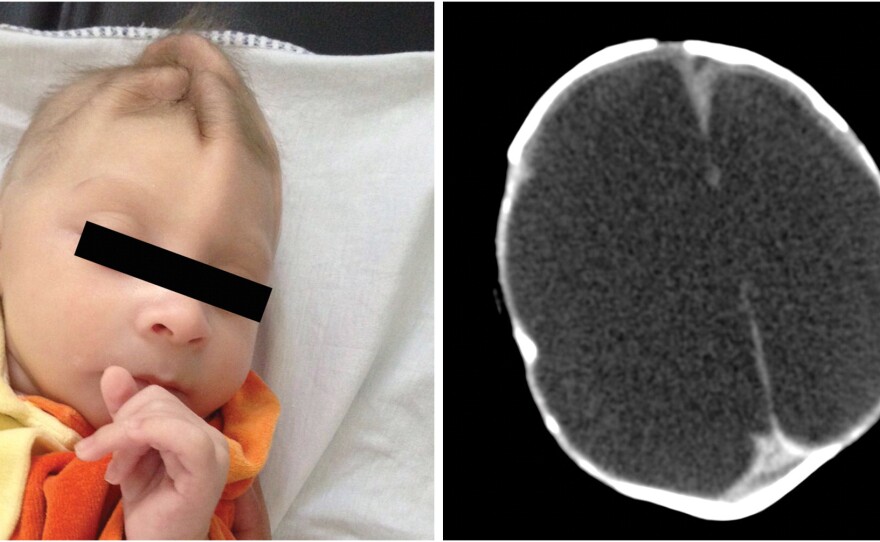

Many research studies and news stories have focused on microcephaly — a condition in which babies are born with very small heads, Levine says. But that defect is just the tip of iceberg of what Zika does to a fetus's brain. "We've illustrated some of those other problems in the study," she says.

For example, one baby in the study was born with a normal-size head. "But when you look inside the brain," Levine says, "there's very little brain tissue present."

MRI scans at 36 weeks of pregnancy showed the fetus's brain was filled with fluid, which had puffed up the size of the skull. And the baby was missing parts of the nervous system, including sections of the brain stem, the spinal cord and the midbrain, which controls eye movements and processes information from the eyes and ears.

The baby also had a flattened skull and extra skin around the head — which is likely caused by the skull collapsing in on itself after the brain stopped growing early in development, the researchers write.

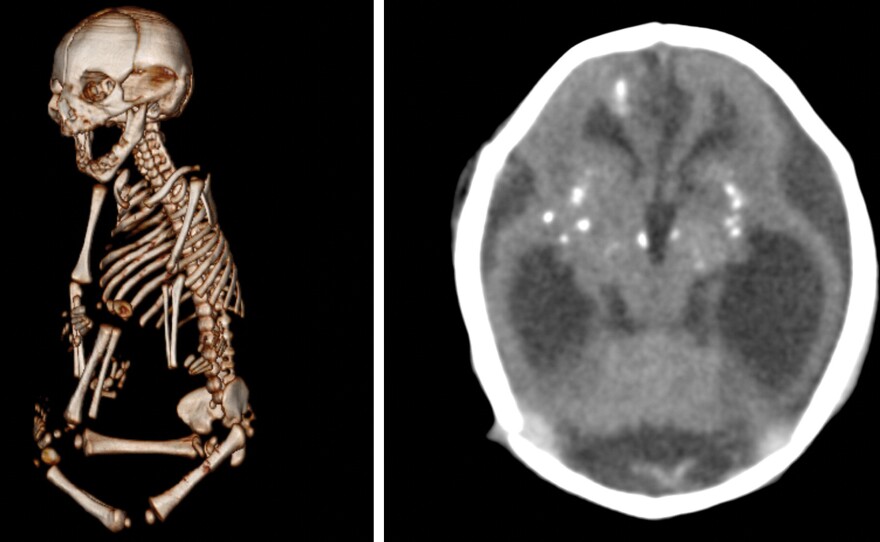

For the study, Levine and colleagues analyzed medical images of 46 fetuses and babies born to mothers who had Zika during pregnancy, including a set of twin girls. The data set included images from 93 ultrasounds, 23 MRI and 41 CT scans taken at the Instituto de Pesquisa in Campina Grande State Paraiba in northeastern Brazil. Doctors also performed autopsies on three babies, who died shortly after birth.

In almost all cases, the babies had damage in the cortex, the outer layer of the brain that controls a huge number of high-level functions like problem-solving, emotion and language. The cortex contains many folds and gives our brains its characteristic shape. But in these babies, oftentimes, the cortex was smooth, Levine says.

"These babies will not be able to behave normally after birth," Levine says. "The question is will they be able to see, hear and move normally."

All the babies had scars in their brains, called calcifications. These are a telltale sign of an infection, Levine says, and show where the virus has injured the brain — or stopped its development.

The babies also had damage in the brain stem, which controls involuntary actions, like breathing and heartbeat, as well as injuries in the cerebellum, which coordinates muscle activity and voluntary movements.

"These images show what happens in the most severe cases of Zika," Levine says. "What we don't know right now is what [milder] cases look like."

In other words, could babies who look normal after birth actually have long-lasting neurological problems because of Zika? "It's too soon to answer that," she says.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.