Flared-leg pants, oversized glasses and hats. Unflinchingly proud expressions. Groovy dance moves.

This was the youth culture of 1960s and 1970s Bamako, the capital city of Mali. And it was captured by Malian photographer Malick Sidibe, bringing international recognition and big deal awards. And it's being celebrated in the first major posthumous exhibit of his images, "Malick Sidibe: Mali Twist," which is at the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain In Paris through February 25. Sidibe died in April 2016 at age 80.

Sidibe's history with photography is a fascinating one. He was born in 1935, and spent his childhood "walking barefoot in the bush with the oxen," he told Brigitte Ollier, who developed the current exhibit with curator Andre Magnin, a longtime admirer of Sidibe's work. But Sidibe's father decided he should study. At school, Sidibe discovered he had a knack for drawing. His artistic ambitions shifted, however, when he landed a job working for a photographer. Before long, he opened his own place, Studio Malick, which beckoned with a neon sign — and the chance for immortality.

"I think photos are the best way of living a long time after you die," Sidibe once told Magnin. "That is why I invested my whole soul in them, my whole heart, to make my subjects more beautiful."

Visitors to the exhibit can see vintage prints as well as some made exclusively for "Mali Twist" from negatives preserved by Magnin. Here's a sampling.

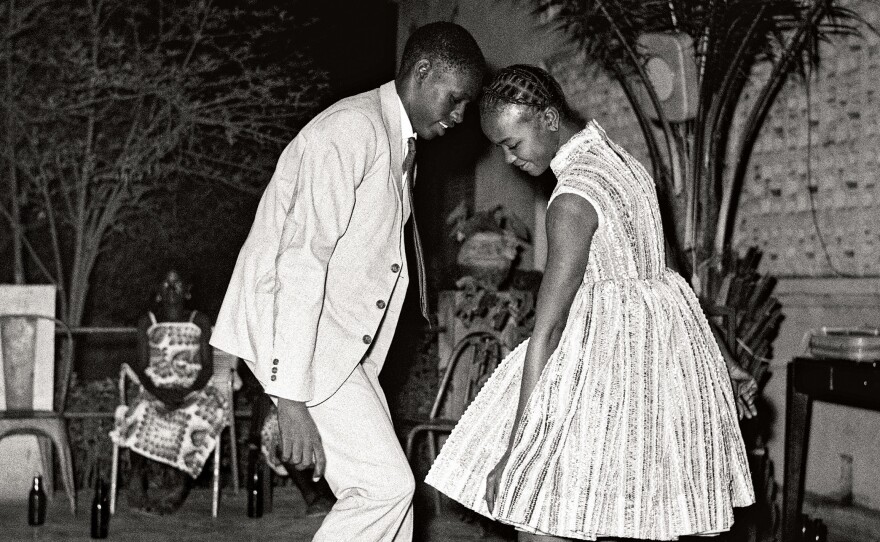

Nuit de Noel, 1963

Named one of the 100 most influential images of all time by Time Magazine, this photo taken at the Happy Boys Club on Feb. 23, 1963 — the eve of Ramadan — was the product of serendipity. Ollier notes that the two teenagers are brother and sister, and she had been dancing with other partners earlier in the night. But Sidibe was ready with his camera at just the right time, as usual. As Magnin writes, "His photography was based on what loomed up, what happened by chance, the good connection. He counted on presence, immortalized moments. Nuit de Noel, with its infinite softness and gentleness, is an instant snatched from time."

Fans de James Brown, 1965

Whether it's a motorcycle, a radio or in this case, a James Brown album, the young people posing for Sidibe liked to showcase their most prized personal possessions, writes Yale University's Robert Storr, who met Sidibe in 2007 — and was photographed by him — while preparing for the Venice Biennale. ("Without the premeditated verve of his local subjects I was unable to rise to the occasion sufficiently to make the picture memorable," Storr admits in his contribution to the exhibit catalog.) Sidibe, in an interview with Magnin, offered his theory on why music mattered so much to the youth of Bamako in that era. "This is only my opinion, but I think young people in those days really liked the twist and rock and Afro-Cuban music because it allowed boys and girls to dance together, touch one another, and dance close," he said. "That was not possible with traditional music."

Les faux agents du FBI, 1974

In an interview with Magnin, Sidibe explained his regular routine: "I would be in my studio until 10 or 11 at night, because the nightlife started late. Then I would go off to the clubs with my bike, until 5 in the morning!" At each stop during the evening, he'd announce his arrival by letting off his flash, which was met warmly by the young revelers, who were excited to welcome him into their world. "I went to their parties like I would go to a movie or a show. I moved about, always looking for the best position. I was always on the lookout for a photo opportunity, a lighthearted moment, an original attitude or some guy who was really funny," he said.

Pique-nique a la Chausee, 1972

The setting changed on hot Sundays, when folks gathered by the Niger River. "People took picnics and we spent the day out there," Sidibe explained. "The boys would bring battery-operated record players and records. We made tea, swam and danced in the open air. I took a great deal of off-the-cuff photos, and I liked doing that a lot. You might get the impression that these photos are posed but in fact they are nearly always natural."

A la plage, 1974

It's Sidibe's perspective that makes his photos stand out, according to Storr, who writes, "Sidibe's is an intimate, avid, nonjudgmental insider's view of the people of his generation, his town, his milieu." Sidibe himself recognized the importance of his relationships with his subjects. He said, "I was an elder for all those young people. They looked up to me rather than respected me. It was better for me that way because if people respect you too much they do not dare to have fun with you."

Circa 1969

The challenges of studio work were what made it appealing to Sidibe. "You had to arrange the person, find the right profile, light the face properly to catch the outlines and features, and find the right light to make the body look beautiful. I also used makeup. I used positions and attitudes that suited the person well," he said. And he cared about the details: "You have to be careful because the photo might be ruined by a mere blink of the eye, which could make the person look tipsy."

Un jeune gentleman, 1978

Filmmaker Manthia Diawara, an NYU professor, reminisces about growing up three blocks from Sidibe's studio. "My brothers, friends, and I used to go to Chez Malick, not only to have our pictures taken but also to admire the photographs of Bamakois we admired most in their bell-bottom pants, large belts with copper buckles, 'chemises cintrees,' and Afro hairdos a la Jackson Five."

Les amis dans la même tenue, 1972

"When I look at Sidibe's photographs today," Diawara writes, "they still remind me of all the dance steps that we used to do in the late 1960s and early 1970s, from the twist to the pachanga, the jerk, the "glissade," and the camel walk."

Sidibe, joking with Diawara, once told him a joke about Diawara's ethnic group, the Maraka: "One day, a Maraka man, who had just returned from Paris, came to my studio to be photographed. He had brought along his favorite perfume and put it on right before I took the picture, thinking that people will smell the perfume, when they see the photo!" Diawara writes, "I still believe that you can smell the perfume coming out of the well-dressed men and women in his photographs; similarly, you can hear the music, see, and admire the dance moves of the youth of Bamako."

Vicky Hallett is a freelance writer in Florence, Italy. She was previously a reporter and fitness columnist for The Washington Post.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.