New data show that San Diego County has among the lowest levels of annual wildfire smoke exposure compared to other counties in California.

“San Diego, in some sense, is in a lucky spot,” said Marshall Burke, professor of environmental social sciences in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “It's by the coast, and a lot of times the wind blows from the coast.”

But even at its relatively low levels, the county has seen small but statistically significant increases in respiratory hospitalizations and mortality rates.

That’s according to a study published last month in the peer-reviewed journal, Nature.

“We love living in San Diego because the climate is beautiful,” said Carlos Gould, assistant professor at UCSD’s School of Public Health. “Even though we’re having a relatively temperate climate, even though we have relatively little smoke, when we are exposed, we do face health consequences.”

Gould, Burke and other researchers from Stony Brook University, Stanford University, the University of Washington, Princeton University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration developed the report.

They warn that wildfire smoke could lead to 71,400 more deaths per year by 2050 in the United States if preventative measures aren’t taken. San Diego County alone could see hundreds more deaths annually by midcentury.

They examined years’ worth of U.S. death records per county, wildfire data, and surface smoke particles using satellite and machine learning models to understand how wildfire activity may change under future warming and how that affects mortality.

“A pressing question for the U.S. and globally is understanding the expected health impacts from wildfire activity now and in the future,” said Gould. “We know that as the world warms, that wildfires are becoming increasingly common.”

But wildfires are complicated to model, he added. Factors such as temperature, human activity, where people live, the surrounding organic matter and rainfall can all shape where and when wildfires occur.

“This paper ties it all together,” Gould said. The impacts of wildfire smoke on mortality are going to be very large, he said.

The study found that California could experience between 6,700 and 7,900 excess deaths due to wildfire smoke by 2050. That’s about 4,500 more deaths a year than today, driven by projected increases in wildfire activity as the climate warms.

San Diego County has seen an average of about 130 excess deaths each year attributable to wildfire smoke, said Gould. In future scenarios, the county could average between 480 and 590 excess deaths annually by midcentury, he added.

Researchers based their estimates on three climate scenarios: low, intermediate and high emission situations.

These warming scenarios are called the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, which the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses for climate research. They serve as guideposts for emissions reductions.

Areas with frequent or severe wildfire smoke exposure are not the only ones seeing notable increases in deaths and asthma. So are places with low, annual levels of wildfire smoke exposure, researchers said.

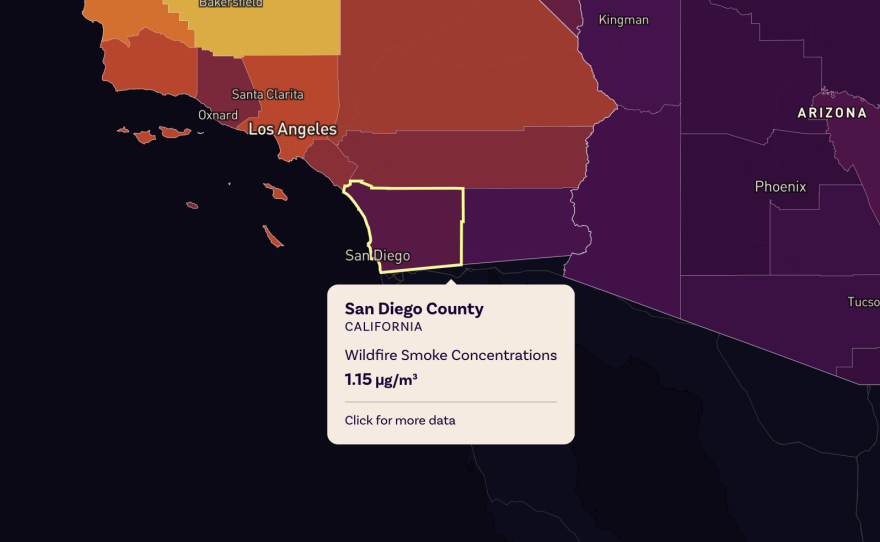

San Diego County is among those areas, according to data from the Environmental Hazard Adaptation Atlas. Stanford published the atlas last month in conjunction with the wildfire smoke study.

Over the last five years, the county has averaged wildfire smoke concentrations of 0.42 micrograms per cubic meter, according to the atlas. Anything below 1 microgram per cubic meter is considered a low annual concentration. For comparison, Mono County, which faces greater wildfire likelihood than 90% of counties in the nation, has average concentrations of 4.73 micrograms per cubic meter, the atlas showed.

When wildfire smoke pollution spiked in San Diego County from about 0.04 cubic micrograms in 2019 to 1.15 cubic micrograms in 2020, mortality from smoke exposure and emergency department visits for wildfire smoke-induced asthma also jumped. Mortality increased by about 1% in 2020, “which might sound like a small number,” Burke said.

“But it’s actually a pretty meaningful increase when you’re tracking things like excess mortality,” he said.

Emergency department visits for wildfire smoke-induced asthma also increased by 60% on the worst smoke day in 2020, according to the atlas.

San Diego County had several wildfires in 2020, with the largest one burning more than 16,000 acres near Alpine. That year was also California’s largest recorded fire season.

So far this year, San Diego County has had more than two dozen fires, according to Cal Fire. Parts of Southern California are experiencing some of the largest increases each year in fire weather days, when conditions are hotter, drier and windier, according to data from the nonprofit Climate Central.

Wildfire activity near or far has an impact on local resources, said Dr. Rajat Suri, a pulmonary and critical care physician at UC San Diego Health.

“The burden definitely increases on our outpatient clinic and then, as a result, our urgent care and emergency rooms as well,” he said, adding that wildfires from earlier this year in Los Angeles not only impacted North County residents, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or COPD, but they also brought Los Angeles residents south for care.

The research team underscored an “urgent need for wildfire smoke adaptation if damages are to be avoided.” Adaptations could include more fuel management, such as prescribed burning to reduce the likelihood of extreme wildfires during changing climate conditions. They also suggested better informing people about the dangers of smoke pollution and how to protect themselves.

Suri said people should try to avoid exposure as best as possible and use masks and home air filters.