Behind the kitchen counter of her City Heights apartment, Fatima Ahmed rolls out a slab of buttery dough. She cuts it into triangles and drops one into a pot of boiling oil.

"This is mandazi, like bread. Flour, yeast and sugar. Just a little bit of sugar, not too much, with eggs to mix it in," she said.

Ahmed cooks these traditional Somalian snacks a lot now, so she can reduce her stress.

She moved to the United States as a single mother over a decade ago to escape civil war in Somalia, where her husband was killed. She feels safer here, but recently the COVID-19 pandemic and protests against police brutality have made her anxious.

She lost her job, is worried about paying the bills and is scared that her children will face violence.

"Sometimes, when I’m stressing so much about my children, I don’t get sleep. And when you don’t sleep, the body hurts. My whole body just aches and hurts." — Fatima Ahmed.

Ahmed spoke in Somali and was translated by her niece, Faiza Warsame.

"Will they get the COVID-19, will they face any problems with the police? There is so much worry that goes into my head when they don’t give me a call back," Warsame translated.

Ahmed said she doesn’t know any therapists that speak Somali. She talks to friends and family to feel better. But, she said she sometimes takes painkillers before sleeping to alleviate her pain.

"Sometimes when I’m stressing so much about my children I don’t get sleep. And when you don’t sleep the body hurts. My whole body just aches and hurts," Warsame translated.

Chronic Discrimination Is A Medical Issue That Doesn't Go Away

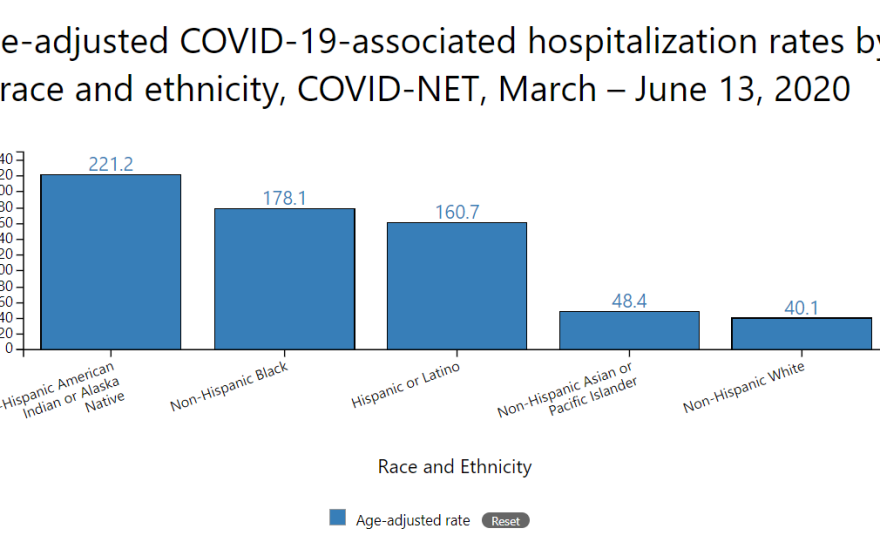

National data show Black and brown communities are being hit the hardest by the coronavirus pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control shows in June 2020 data that for age-adjusted populations, non-Hispanic Blacks are about five times more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be hospitalized due to coronavirus.

Brown communities are four times more likely to be hospitalized than whites.

In fact in San Diego, Latinx communities make up around 60% of coronavirus hospitalizations. But they make up only a third of the population.

Many public health officials, including San Diego’s public health officer Wilma Wooten, say the trend can be explained by underlying health conditions like obesity, hypertension and stress.

The county has also said the Hispanic population might see this trend because they "often show more physical affection."

But some academics say that explanation isn't a fair picture. University of Southern California neuropsychologist April Thames said racism is a chronic form of stress that can’t be treated medically.

"There are certain stressors that are more frequent in ethnic, racial minority populations, for example poverty," Thames said. "Then there’s a type of stresser that’s different, and that’s stress that’s directly tied to your race. It's always in the air, if you will."

Thames says chronic stress for people of color is tied to uncertainty. Will I be stopped by a police officer today? Will I be judged? Will I be harassed?

Thames and her colleagues looked into the science of how this anticipatory anxiety biologically affects the body. The research was published in 2019 in a peer-reviewed journal.

The study looked at HIV positive and negative patients across different racial groups to see how they produced immune responses. There are certain genes, or parts of our DNA, that regulate how we handle pathogens, like a virus. Some promote a inflammatory response, which in large doses could lead to cellular damage. Other genes promote an antiviral response that helps fight off disease.

"We wanted to see Black and white differences in this pattern of gene expression that we know could make someone very susceptible to disease and chronic illness," Thames said.

"And we saw that Blacks, more so than whites, had this pattern of sort of, if you will, susceptible gene expression. We saw increases in genes that would promote the inflammatory response and a decrease in genes that would promote the antiviral response, which is all part of innate immunity," Thames said.

Thames said all the people who were studied had similar socioeconomic backgrounds and access to healthcare.

"Because if we think about what it actually means to be discriminated against, it is a threat to your eventual survival." — April Thames, USC.

"The only potential stresser that differed between the two groups was discrimination experiences," Thames said.

Thames said discrimination accounted for more 50% of the difference in gene expression that caused more inflammation within Blacks than in whites.

The research suggests stress from chronic racial discrimination not only causes issues like high blood pressure. She says it also biologically makes it more difficult for people to fight off diseases, like coronavirus.

"It's like getting hit once. It's nothing, you know. But if you continue getting hit, you're going to result in injury. And that's what I see is happening with these chronic experiences of racism and discrimination," Thames said.

"Because if we think about what it actually means to be discriminated against, it is a threat to your eventual survival."

Factoring Racism And Mental Health Into A Medical Response

So, it’s not only Black mothers that are worried. A number of young Black men from City Heights launched a community mental health support group about three years ago.

They get together in the corner room of the nonprofit group United Women of East Africa office. Sometimes they play board games or shoot hoops at a nearby basketball court. But mostly, they just talk.

Abdirazak Ahmed is one of the organizers. He opens up the conversation with a simple question.

"How is everything going for you guys? I know we haven't met in a long time. What's it like being away from the from the space we have?" he said.

This Saturday in late June was the first time these men have gotten together since the pandemic started. Many of them don't have laptops, so Zoom wasn't an option. They're relieved to be back at this space, which they call the Hub, said Ahmed.

"It's like a safe spot. It's better to come here because it's always like people that's gonna keep you in check. We used to hang out in the park. That's not the safest place to be after the sunset, especially in this community," he said.

As Black people we have this aura of getting over it. You know, be strong. But, that's not how it should be. — Abdi Hussein.

But not everyone in at-risk communities have this type of outlet. One participant, Abdi Hussein said there is a stigma within the Black community, and especially the East African immigrant community, of admitting you need help.

For example, one of the men said his GPA had gone down from a 4.0 to a 3.5 since the pandemic started, because he doesn't have a laptop and can't do his studies as well. This type of stress is constant, but hard to talk about, they say.

"It gets brushed under the rug. As Black people we have this aura of getting over it. You know, be strong. But, that's not how it should be. It’s already hard as a teenager and young adult going through changes, and on top of that you add racism," Hussein said.

Hussein says the younger Black generation is increasingly recognizing how critical mental health is. But he feels that people outside the community are still not seeing it, even those who work in the medical field. Many of the men say they feel like they can’t trust therapists who don’t look like them.

"Somebody will muster all this confidence to finally go see a professional. And then it will be some person who doesn't know your culture. They don't know where you come from. And they might say something insensitive. And the person is all of a sudden turned off by it and think this validates what I was concerned about all along," Hussein said.

"From a professional standpoint the institutions that exist have to have cultural competency. There are people who are Somali that can fill these jobs. Hire them!" he said.

As communities of color continue to be hit the hardest by the pandemic, it's not just these young Black men who are asking for change. Scientists say racism, which causes chronic stress, is a key medical issue that has to be factored into the public health response.