First of two parts

As Mexico approaches its election day on July 1, polls indicate the candidate for the opposition Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, is well ahead and appears likely to return his party to power.

The PRI governed Mexico for seven decades until 2000, when it was tossed out by an electorate tired of a corrupt political machine. Now, discontent with the current leadership and the rampant drug-related violence has created an opening for the PRI to come back. Still, some Mexicans are queasy about the prospect of the party's resurgence.

Every day, a color guard stands at attention under Mexico City's Monument to the Revolution — an arched stone colossus that commemorates the country's violent upheaval that gave birth to modern Mexico. Interred here are the heroes of the Mexican Revolution, including Plutarco Elias Calles, the father of the party that came to be the PRI.

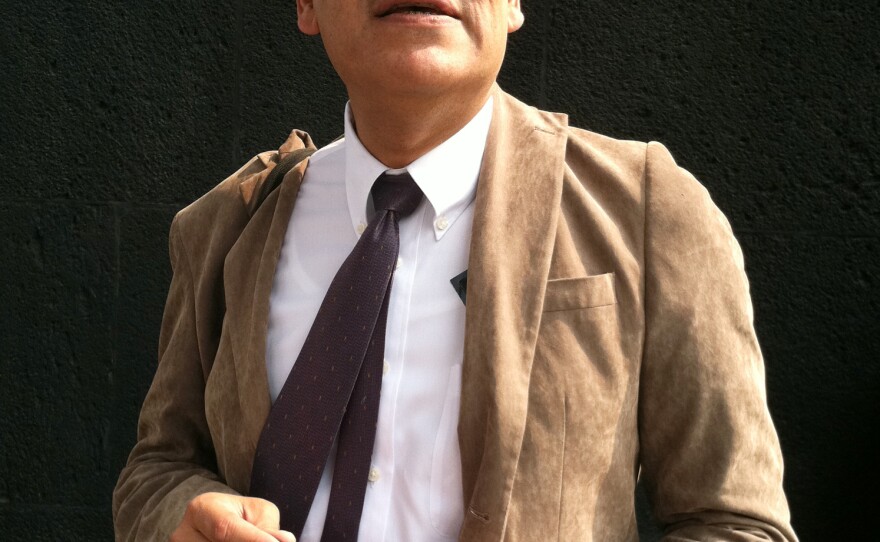

Fred Alvarez, a political consultant and blogger, says what Calles did was to create a unique party, like the Cuban or Russian Communist Party.

"The PRI even adopted the colors of the national flag — red, white and green — and made them the party colors," Alvarez says. "What Mexicans do not want to see is a new state party where President Pena Nieto becomes the party chief. This would be wrong."

Alvarez is referring to the PRI's presidential candidate, Enrique Pena Nieto, the 45-year-old former governor of Mexico state, who has a serious demeanor and movie-star good looks. Polls put Pena Nieto ahead of his rivals by more than 10 points. The leading challengers are Manuel Lopez Obrador, of the leftist Party of Democratic Revolution, or PRD, and Josefina Vazquez Mota, who represents the conservative, deeply Catholic Party of National Action, or PAN, which has been in power for nearly 12 years.

"Why do I want to be president?" Pena Nieto asks in a campaign spot. "Because our country deserves to be better; because I want to change Mexico."

Desire For Stability

Mexicans over 30 remember Pena Nieto's PRI as the party that brutally suppressed a student protest in 1968, that presided over financial crises in the 1970s and '80s, and that used the state-owned oil company as its personal ATM.

But Mexico was stable. Today, the country is agonizing through an epidemic of cartel violence that has killed more than 50,000 people and seen major cities lost to thug rule.

"The only thing that is driving people to vote for the PRI is the perception that these things that are happening now did not happen in the days of the PRI," says Mexican author and historian Enrique Krauze. "Then, we had corruption, yes, but we had peace and order. I think that is something that is drawing many people towards the PRI."

Krauze does not believe the PRI could ever become "the state party" again, when it controlled elections, the Congress, the state governors, the unions and the media. Today, he says, Mexico has moved too far down the path toward democracy.

"The restoration of the PRI we knew, I think, is truly impossible," he says. "This is a different country."

Back at the Monument to the Revolution, on a sunny morning, a vendor named Maria Resendiz takes a break in the shade. Her drawn face bespeaks her hard life selling cigarettes, candy and Chiclets on the street. She describes herself as a lifelong PRI-ista.

"I'm not naive; sure, there was corruption in the PRI, but that was their work and they let us do ours," Resendiz says. "That's why we didn't mind when they asked for a 10-peso bribe."

Generational Divide

A new generation of Mexicans has not inherited these old party loyalties. They're young and independent, wired, well-informed and deeply skeptical of traditional Mexican politics.

Last month, thousands of university students marched through the streets of Mexico City denouncing Pena Nieto and the PRI.

On a recent evening, a classroom of political science students at the prestigious ITAM university in Mexico City is asked to come up with a one-word description of each leading presidential candidate. Their answers are revealing.

Vazquez Mota of the PAN: "False," "maternal," "more of the same," "innocent."

Lopez Obrador of the PRD: "Combative," "retrograde," "old," "incites hatred."

Finally, front-runner Pena Nieto of the PRI: "Corrupt," "cretin," "fool," "puppet," "immoral."

Has The PRI Changed Enough?

Pena Nieto takes pains to tell Mexico the PRI has changed, that during its political exile the party has become honest and democratic. Its platform differs little from the PAN on education, security and job creation. To win, the PRI simply has to capitalize on public discontent with the party in power.

To that end, at the first presidential debate held last month, Piena Nieto gripped his podium and peered into the television camera.

"Mexico has to be different," he said, "and for this I insist the same ones cannot keep governing."

A few moments later, Lopez Obrador, the white-haired candidate of the left, spoke.

"Do you all really believe that if the PRI returns, things will get better in this country?" he asked with a smirk, knocking on the lectern with his knuckles. "You'd better knock on wood."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))