During the 1930s, as Adolf Hitler was rising to power in Germany, the man who would turn out to be his most implacable foe was drowning — in debt and champagne.

In 1936, Winston Churchill owed his wine merchant the equivalent of $75,000 in today's money. He was also in hock to his shirt-maker, watchmaker and printer — but his sybaritic lifestyle, of a cigar-smoking, horse-owning country aristocrat, continued apace.

Stories of Churchill's special relationship with alcohol are legendary. Eleanor Roosevelt, who was his host at the White House during World War II, was astonished "that anyone could smoke so much and drink so much and keep perfectly well."

Churchill started his day with whisky, but it was champagne that was his truest passion — and now, for the first time, we get a glimpse into the extent to which that passion imperiled his already threadbare bank balance.

In a magnificently researched new book titled No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money, David Lough, a retired banker who read history at Oxford University, recounts the unbelievable story of the former prime minister's fiscal excesses. After years of sifting patiently through Churchill's bank statements and bills, Lough, a skilled financial gumshoe, has amassed a trove of material that he deploys to great effect in his book.

We learn of Churchill's ruinous stock market speculation circa 1929 and the inheritances he squandered; his gambling rousts at the casinos in Biarritz and Monte Carlo; the thousands of pounds he sank into the upkeep of Chartwell, his beloved country mansion in Kent; and the unceasing torrent of cash he poured into maintaining a first-rate cellar.

To get an idea of Churchill's annual alcohol consumption, here's what he ordered in 1908, the year he married Clementine:

Lough never ceases to marvel at how such a prominent public figure got away by living his life well over the overdraft and alcohol limit — though he is more bemused than judgmental. (Far more scathing is Christopher Hitchens, who, in an excellent essay for The Atlantic, compared the prodigal and overindulged Churchill of the '30s to Shakespeare's glutton Falstaff, "so surfeit-swell'd, so old, and so profane." )

Perennially late on his taxes, Churchill loathed the taxman as much as he did the Nazi, and while he defeated the latter, he spent his whole life trying, rather less successfully, to dodge the former. The taxman may have proved intractable, but others were more amenable. Rich friends bailed him out, and at one point, the government settled his liquor bills — something unthinkable today.

Every once in a while, when his creditors threatened to reel him in, Churchill would attempt to tighten his belt. The book's title is taken from a note he left Clementine in 1926, ordering, "No more champagne is to be bought. Unless special directions are given only white or red wine, or whisky and soda will be offered at luncheon, or dinner. ... Cigars must be reduced to four a day." In addition, he ordered that all the cattle, chickens, pigs and ponies at Chartwell be sold and that there be no fish course unless there were visitors.

Churchill clearly needed prodigious amounts of alcohol to function, so fortunately for him — and the free world — he had a patient wine merchant. "Randolph Payne & Sons had been the Churchill family's wine merchants for generations," says Lough. "They were a top-end-of-the-market firm who carried the 'royal warrant' on their letterhead: 'By Special Appointment to Her Majesty The Late Queen Victoria and to The Late King William The Fourth.' "

The firm gave Churchill a long rope, but when his outstanding balance touched what is today's equivalent of $75,000 (as it did in 1914 and 1936), the chairman was forced to write to him — triggering yet another fit of economizing that fizzled out faster than an uncorked bottle of Pol Roger.

If Churchill drank his way into debt, he wrote his way out of it. Before he was a politician, he was a journalist, and newspapers vied with one another for his stirring copy. He is easily one of the most highly paid freelance war correspondents in history, and certainly the most lavishly equipped. When he sailed to Cape Town to cover the Boer War in 1899, he took six cases of wine and spirits to enliven the three-week voyage. At Bloemfontein in South Africa, his battle kit comprised an ox-wagon "full of Fortnum & Mason groceries and of course liquor."

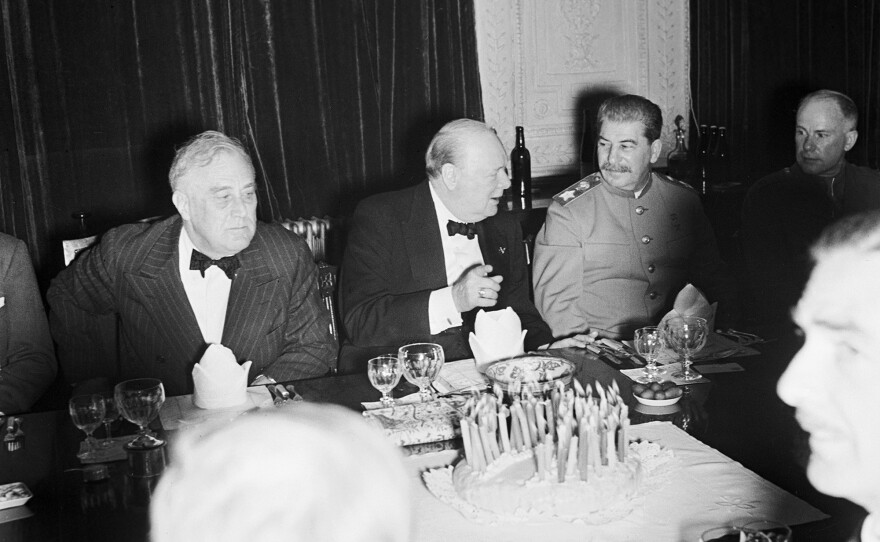

Churchill drank several brands of champagne such as Giesler, Moet et Chandon, and Pommery, but Pol Roger was his clear favorite. Every year on Churchill's birthday, the charming and shrewd Odette Pol Roger sent him a case of champagne. (His other great friend, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, sent him caviar — until they fell out over Churchill's Iron Curtain speech.)

When Churchill died in 1965 at the mellow age of 90, Pol Roger put a black border around the labels of bottles exported to Britain. Madame Pol Roger was among the few personal friends invited to the funeral service at St. Paul's Cathedral. In 1984, no doubt to solder the Churchillian connection, Pol Roger launched a full-bodied cuvée named Sir Winston Churchill.

The Churchill historian Michael Richards describes a game Churchill was fond of playing with his friend Frederick Lindemann, the Oxford don who was the government's chief scientific adviser.

"Prof!" Churchill would command. "Pray calculate the total quantity of champagne, wine and spirits I have consumed thus far in my life and tell us how much of this room it would fill."

Lindemann would pull out his slide rule, pretend to make calculations, and announce something on the lines of, "I'm sorry, Winston, it would only reach our ankles." And Churchill would mock sigh, "How much to do — how little time remains."

Nina Martyris is a literary journalist based in Knoxville, Tenn.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))