A young Chalino Sánchez, clad in Western wear and a cowboy hat tilted to one side, could be found selling tapes of his corridos at swap meets or entertaining guests at quinceañeras and baptism parties throughout Southern California in the 1980s.

He was just another Mexican immigrant hustling to survive. But within a few years he became a bestselling singer whose music flowed from California to Mexico, mesmerizing fans with his songs about outlaws and drug traffickers.

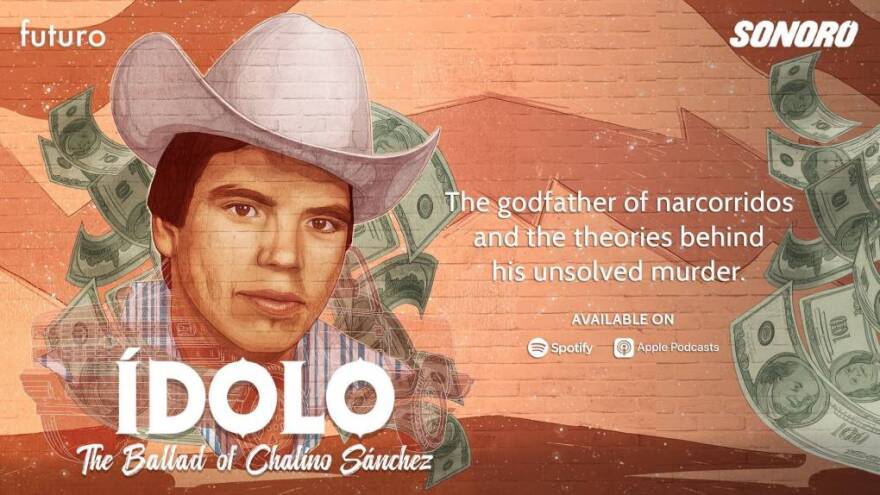

His rise to superstardom, however, was cut short by his still unsolved murder in 1992. Sánchez’s remarkable story takes on new life in Idolo: The Ballad of Chalino Sánchez, an eight-part podcast co-produced by Futuro Media and Sonoro that dropped onto streaming platforms on Feb. 1.

Sánchez is considered the king of narcocorridos, a musical genre that some critics say glamorizes the crime, violence and misogyny that has plagued Mexico for decades.

'Corridos remind you of what your abuelitos listened to, what your parents or your tíos and tías listened to. And, it is a form of literacy. It's a form of reading and writing.' — Cati V. de los Ríos, assistant professor, UC Berkeley Graduate School of Education

Still, something about the raw sound of his voice, his rags-to-riches story and his swagger continue to capture fans. You’ve probably heard his tunes even if you only casually listen to Mexican music. Thirty years after his death, the deeply reported Idolo takes a personal look at the singer who was only 31 when he was found shot to death in an irrigation canal the morning after a concert in his home state of Sinaloa.

The podcast comes in two versions, with host Erick Galindo telling the story in English, from California, and host Alejandro Mendoza telling it from Mexico, in Spanish.

“I've been trying to tell this story professionally in mainstream media for like 10 years,” said Galindo, a writer, producer and host for LAist Studios. “[Sánchez] represented so much across cultures. He gave recent immigrants something nostalgic from their ranchos back home, and at the same time helped their children connect with their parents' culture.”

The history of corridos in Mexico goes back centuries, but the genre has evolved, according to Jorge Herrera, an ethnomusicologist and expert on Mexican music who teaches at California State University, Fullerton. In the past, a corrido would summarize or use figurative language to describe crimes or violence, whereas Sánchez used graphic details in his tales of valientes, or brave men, often desperados trying to avoid capture.

Generations of young Mexican Americans have found “a piece of their dignity in his voice, a piece of their story and their family story in his songs,” said Cati V. de los Ríos, an assistant professor at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Education, who has researched how students of Mexican descent relate to corridos.

“Corridos remind you of what your abuelitos listened to, what your parents or your tíos and tías listened to,” she said. “And, it is a form of literacy. It’s a form of reading and writing. It’s through corridos that a lot of young people learn allegory, hyperboles, similes and metaphors.”

Galindo, whose parents are from Sinaloa, was focused on telling Sánchez’s story in a way that would appeal to other Mexican Americans who also grew up idolizing the singer. The podcast also probes some of the unanswered questions surrounding the singer's mysterious death.

“Everybody can find something that they like in this story,” said Jasmine Romero, head of development at Sonoro. “It's a music story. It's a true-crime story. It's a murder mystery. It's got all of those different elements that make it appealing to all kinds of people.”

Sánchez’s songs, which have hundreds of millions of streams on online music platforms, continue to bump from home stereos. He is often compared to hip-hop artists whose music chronicles the stories of struggling people resorting to crime to get by.

“Chalino is Mexican, but then goes to LA and is so influential and iconic on both sides of the border,” Romero said. “His career took off because of mixtapes that came out of swap meets in LA. That is, in essence, how he got discovered and how he blew up. I think people underestimate the influence of word-of-mouth in the Mexican American community.”

The podcast delves into how Sánchez became a successful performer despite not being a trained singer, or even a particularly talented one.

“Chalino couldn’t have been famous in Mexico,” said Galindo, whose independent production company, Sin Miedo Productions, also co-produced Idolo. “There's too many great singers in Mexico. There's too many people who already represent what he represented for millions of immigrants in Los Angeles and in the Bay Area and in Central California.”

But what set Sánchez apart was a singing style he himself referred to as “barking,” and that Galindo describes as “raw and rugged.”

“His fans felt like outsiders,” said Galindo. “It’s the idea that you're in this country, and you don't feel like you belong. And here's a guy who definitely does not sound like he belongs on stage. And he's doing it anyway.”

Sánchez’s first corrido was about his brother, who immigrated with him to California, and was later killed back in Mexico. The song, “Armando Sánchez,” offers details about the slaying, describing a valiant man who was shot seven times on Dec. 5 at the Santa Rita Hotel in Tijuana by a coward who didn’t give him the chance to react. (The song doesn’t reveal the year of his brother’s death.) Sánchez’s penchant for specificity and paying homage were trademarks of his compositions. (Check out this primer on some of his most well-known corridos.)

As Idolo details, Sánchez spent time in La Mesa prison in Tijuana following his brother’s death. It was there that he honed his songwriting and storytelling skills, earning money by composing tunes for fellow inmates who wanted to be immortalized in a song.

RELATED: Pandemic, San Diego’s high costs have spurred a migration south

The Idolo production team decided a podcast about Sánchez needed its own corrido, so a group of musicians and vocalists were assembled to evoke Sánchez’s style. The verses include the refrain, “Ni las ballas pudieron matarlo/Su legado aún sigue vivo tanto aquí como en el otro lado” ("Not even the bullets could kill him/His legacy lives on here just like on the other side").

The podcast digs into the question of whether Sánchez normalized narco culture. Sánchez weaved tales of narco activity, but his songs preceded an explosion of cartel violence in Mexico that has spurred the murder of tens of thousands of people in the last decade alone. The violence has become part of people’s everyday lives, especially in places like Sinaloa, where Sánchez came from.

“Musicians are singing about what's going on in Mexico, and you cannot blame that on a corrido,” Herrera, the ethnomusicologist, said. “The narco war, the drugs — all that came first and the music is just a reflection of what's happening.”

Galindo said his goal was to discuss Sánchez in all his complexity.

“He told stories of complicated men, bad guys, sometimes good guys, but oftentimes criminals and violent men,” he said. “But he did tell it in a way that gave them context and dignity. And hopefully, we did that for him.”