Yes, we all get older. But now, getting older has become a video fetish; all kinds of people take pictures of themselves every day for six, seven, eight years and then blend the images together into a ... well, if you've missed the Web craze, Homer Simpson's "Every Day" is a perfect catcher-upper.

Not only can you see Homer switching jobs (cavalryman, Indian, king, infantryman, fisherman, fireman), you watch his body grow, swell, swag. As with all things Simpson, the physical changes are dramatic.

But what these videos don't show are the psychological changes, and one of the most universal changes is that as humans age, they change the way they feel about time.

Faster And Faster And Faster

As people get older, "they just have this sense, this feeling that time is going faster than they are," says Warren Meck, a psychology professor at Duke University.

This seems to be true across cultures, across time, all over the world.

No one is sure where this feeling comes from.

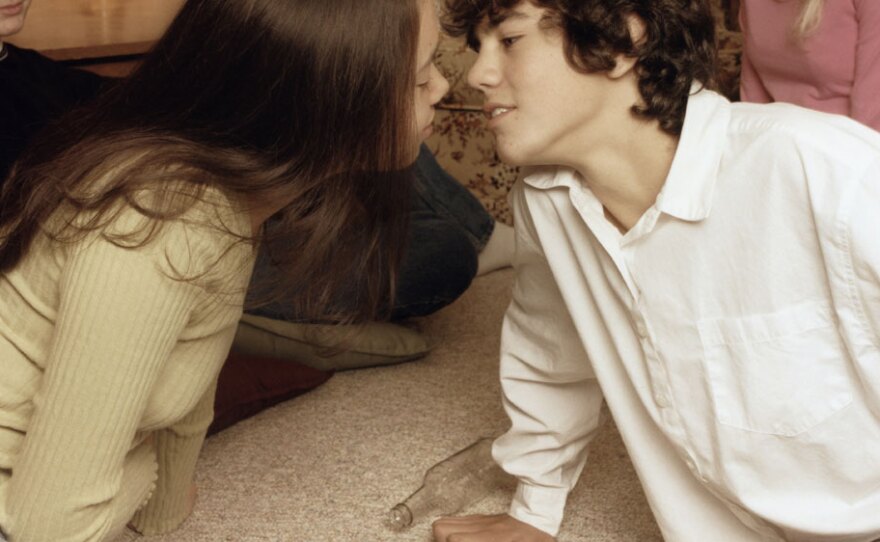

Scientists have theories, of course, and one of them is that when you experience something for the very first time, more details, more information gets stored in your memory. Think about your first kiss.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman of Baylor College of Medicine says that since the touch of the lips, the excitement, the taste, the smell — everything about this moment is novel — you aren't embroidering a bank of previous experiences, you are starting fresh.

Have you noticed, he says, that when you recall your first kisses, early birthdays, your earliest summer vacations, they seem to be in slow motion? "I know when I look back on a childhood summer, it seems to have lasted forever," he says.

That's because when it's the "first", there are so many things to remember. The list of encoded memories is so dense, reading them back gives you a feeling that they must have taken forever. But that's an illusion. "It's a construction of the brain," says Eagleman. "The more memory you have of something, you think, 'Wow, that really took a long time!'

"Of course, you can see this in everyday life," says Eagleman, "when you drive to your new workplace for the first time and it seems to take a really long time to get there. But when you drive back and forth to your work every day after that, it takes no time at all, because you're not really writing it down anymore. There's nothing novel about it."

That may be because the brain records new experiences — especially novel and exciting experiences — differently. This is even measurable. Eagleman's lab has found that brains use more energy to represent a memory when the memory is novel.

So, first memories are dense. The routines of later life are sketchy. The past wasn't really slower than the present. It just feels that way.

There are all kinds of arguments one could have with this theory, but before we poke it, we want you to feel it.

Here's a celebration of dense early memories from a very recently departed (not to heaven, just back to California) intern at NPR, Maggie Starbard. With a bunch of friends (Caitlin Fitch, Mark Turner and Mike Eckelkamp), Maggie decided to dwell on a lazy beach where kids are collecting dense memories by the truckload:

Now for the pokes. Who said that novel experiences belong exclusively to the young?

Older people have novel experiences — lots of them. Some of us have crazier middle ages than youths. We fall in love, out of love. Then our parenting years are filled with watching our babies' first thises, first thats. Retired people travel — if they can afford to — to duplicate some of those rushes of novel experiences.

Yes, it's true, the youngest years are chock full of novelty, but Duke's Warren Meck points out that when you hit your 60s and 70s, and time is beginning to run out, experiences get more precious and once again you remember all the details.

So take this "novelty" explanation for why time moves faster as you age and weigh it as you will.

Other theories may prove more satisfying.

Professors Meck and Eagleman explore a number of them on our All Things Considered broadcast. If you wish to hear the "Aging Brain" theory of why time goes faster, or the "How Long Have You Been Alive?" explanation, they await you at the top of this page, where the button says "Listen."

Special thanks to Dan Madorsky for sound design on the radio story. Warren Meck's work has been featured on the BBC documentaries The Body Clock (1999) and Time (2006). Jay Ingram's essay "Time Passes Faster" (which helped me think through the radio story) is included in a collection called The Velocity of Honey published in 2003. David Eagleman directs the Laboratory for Perception and Action at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. His new novel, Sum, has been featured on NPR/WNYC's Radiolab.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))