The story of America's rise on the global art scene has mostly taken place in New York — but now Los Angeles wants in on the narrative.

Over the past 10 years, the wealthy L.A.-based Getty Foundation has doled out about $10 million in grants to help launch Pacific Standard Time, an unprecedented collaboration between more than 60 cultural institutions with one grand theme in mind: the birth of the L.A. art scene from 1945 to 1980.

For six months beginning in October, large and small museums and cultural venues from San Diego to Santa Barbara will feature artwork that collectively aims to rewrite the history of art in America after World War II.

'Something Great Happened' Right Here

In traditional L.A. style, the exhibition's press preview at the Getty opened with a dreamy, overproduced film that made good use of the project's celebrity cachet: It shows the Red Hot Chili Peppers' Anthony Kiedis bonding with L.A. artist Ed Ruscha.

"I like looking at art that I'm not in anticipation of," Ruscha tells Kiedis in the film.

"You know, I feel the same way," Kiedis replies. "My favorite experience with art is visceral — where I see it, and it just makes me go, 'Oh! Oh! Oh, look at that! Oh! Something great happened right there!'"

And that's the theme of Pacific Standard Time; something great happened right here. The exhibition's art includes everything from L.A. pop to pottery. It covers the tumultuous '60s and '70s; films from the African-American L.A. Rebellion; and Chicano, Asian-American and feminist artwork.

George Herms was part of the L.A. art scene almost from the beginning. He created assemblages and collages out of found objects and was friends with beat writers and poets. Today, Herms is in his mid-70s and still works out of his Topanga Canyon studio near Santa Monica. The Getty asked him to help kick off Pacific Standard Time with a free jazz concert.

"Beauty is your duty," Herms says. "And remember, kids, it's not secondhand smoke that kills. It's secondhand thoughts."

Another exhibition artist studied painting in an unconventional location — an auto-body shop. In the early 1960s, the artist sprayed the hood of a Chevy Corvair with bright colors and patterns, and hung it on the wall. Sound macho? The artist is Judy Chicago. She says the scene was way too macho, but she still owes a lot to the '60s L.A. arts spirit.

"It's freedom from the shadow of European art," she says, "freedom from the shadow of the art market and of New York. It allowed artists to think about making work and not selling work. The idea was to be taken seriously as an artist — that was the goal that we all had."

A Message For The Next Generation

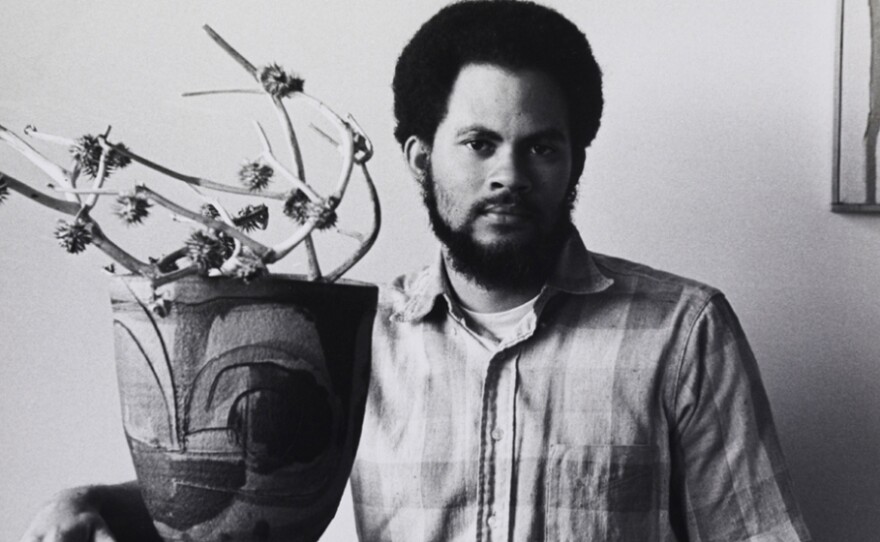

The Leimert Park neighborhood has long been a center of African-American culture in L.A. Dale Davis and his brother ran an art gallery, the Brockman Gallery, there from the mid-'60s to the mid-'80s.

"We had ceramics; we had very fine art prints; we had silk screens," Davis says. "We had art in Leimert Park — in the actual park — hanging on ropes between trees. I guess people would look at it and say, 'Ah, it's very primitive.' But who cares? The idea was we wanted the community to see the art."

In 1969, while fighting the draft, Davis assembled pieces of metal and glazed clay into 4-foot-high bomb-shaped objects. He called it Viet Nam Game and it's in the Pacific Standard Time show called Now Dig This! at the Hammer Museum in L.A.

Davis says he's especially proud of Viet Nam Game's inclusion in the catalog, which also aims to inspire the next generation to learn about the struggles of the past.

"It's what we have needed as minority people; documents that show that we exist and that we have made a difference in the lives of Los Angelenos and, now, the world view," he says.

L.A. As Cultural Intersection

Dora De Larios serves coffee in turned and glazed mugs in her west L.A. studio. The studio also holds 10-foot-high ceramic totems and other cross-cultural works that reflect her childhood in the city and her Mexican heritage.

De Larios' story is symbolic of the way cultures intersect, overlap and influence the L.A. aesthetic. She remembers growing up in a neighborhood that was rich with Japanese immigrants and culture.

"I loved the people, and they all spoke Spanish because our whole neighborhood spoke Spanish," she says. "It didn't matter if you were pink; you had to speak Spanish."

De Larios came to incorporate an Asian aesthetic into her work. Taking a light green porcelain vase with a celadon glaze off the shelf, she admires its quiet subtlety.

"The relief is just an abstraction of brush strokes," she says. "But it doesn't say anything. I mean it's not saying, 'Oh my gosh,' in Japanese or anything. It's just an expression."

Her 1968 glazed stoneware Mother and Child can be seen at the Autry National Center's Pacific Standard Time exhibit called Art Along the Hyphen: The Mexican-American Generation.

'Everything' Is Possible In L.A.

During the 10 years it took to organize Pacific Standard Time, scholars dug deep into archives, interviewing artists, dealers and collectors. Labs restored and preserved the often fragile works, and they documented everything. But in spite of the polished appearance of the collaboration's unveiling, many hope that L.A.'s atmosphere will remain largely the same after the night is over.

Annie Philbin, who directs the Hammer Museum, recalls something L.A. artist Lari Pittman said at a recent gala.

"'This is a moment where L.A. gets to shine and look very glamorous and very polished and very together,' " Philbin recalls Pittman saying. " 'But let's just have that be tonight. And let's wake up tomorrow and still keep it a fixer-upper.' "

As for Philbin, she couldn't agree more.

"I think that's kind of the feeling that everybody has, a little bit. It's like, let's not getting carried away with this," she says, "because we do love that aspect of everything being possible."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))