Ellsworth Kelly, one of the greatest American artists of the past century, has died at 92.

Kelly died at his home in Spencertown, N.Y., says gallery owner Matthew Marks, who has represented the artist for two decades. Kelly is survived by his longtime partner Jack Shear.

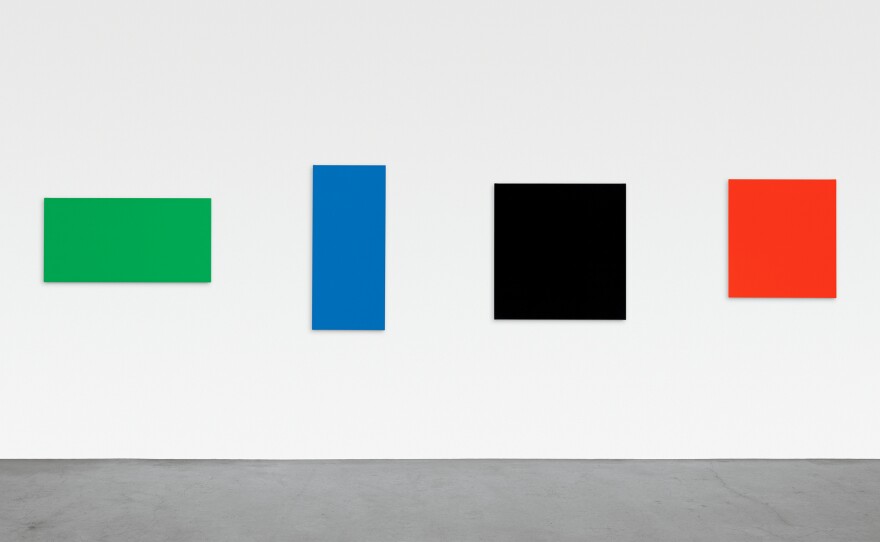

For seven decades, Kelly created pure, strong shapes and colors, immersive and brilliant. His vivid geometric blocks, in sculpture and paintings, are displayed at modern art museums from Paris to Houston to Boston to Berlin.

He started his artistic career in France — but not by wearing a beret and standing behind an easel. He was in a U.S. Army uniform during World War II, serving in a special unit made mostly of artists. Their job was to fool the Germans into thinking there were more Allied forces than there actually were.

Kelly told NPR in 2007 they did it partly by building fake tanks and trucks from wood and burlap.

"But later they were made in rubber — inflatable and they looked like the real thing," he said.

After the war, Kelly lived in Paris. Art historian Sarah Rich says he'd walk around snapping photographs.

"And not photographs of famous places, like the Eiffel Tower, but photos of an alleyway" — or a plain old window, or the side of an unassuming building.

In that photograph, Kelly would see a square. And he would use that black square as the basis of a painting.

Of course, you don't need a photo to paint a black square. You just need a ruler. But Ellsworth Kelly wanted to bring scraps of the world almost mystically onto his canvas.

He boiled shadows and shapes down into abstractions — monochromes, just one strong, pure, bright color. Kelly said that came from his boyhood in New Jersey surrounded by nature.

"I've always been a colorist," he said. "I think I started when I was very young, being a birdwatcher fascinated by the bird colors."

The way Kelly used colors made them feel almost alive. Just to face a giant red rectangle by Ellsworth Kelly is to come to red in a fresh and profound way.

"I feel that I like color in its strongest sense," Kelly told NPR in 2013. "I don't like mixed colors that much, like plum color or deep, deep colors that are hard to define. I liked red, yellow, blue, black and white — [that] was what I started with."

When Kelly moved to New York in the 1950s, abstract expressionism was all the rage. He did not fit in, says Sarah Rich, with all the cooler-than-cool artists flinging paint at canvases — or dripping it, or standing in it.

"He was really not interested in their corny expressionism and epic self-importance," she says. "All of that stuff just seemed burdensome and dull."

Forging a new aesthetic language in that environment was not easy, Kelly said.

"It was a very hard job doing it all by myself, getting to where I am," he told NPR.

Where Ellsworth Kelly was, when he died, was the position of a universally recognized master of contemporary art. He influenced minimalism and pop art with his bold, spare paintings, drawings and sculptures, which are in virtually every major museum of modern art.

When Kelly was 90, NPR asked what he enjoyed most about being very old.

"I feel like I'm 20 in my head," he said. "My painting makes me feel good and I just feel like I can live on.

"If you just keep working, maybe that's possible."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))