Updated May 5, 2022 at 9:11 AM ET

Even in feminist history, Pat Maginnis does not quite command name recognition.

"She was not Gloria Steinem," says writer Lili Loofbourow, who profiled the early abortion-rights advocate in 2018. "She was not an attention seeker or a credit seeker."

Maginnis may have lacked a nose for the spotlight. She wasn't one for glamour — she was known to dress in clothes from thrift stores or even those she found on the street. And she employed confrontational tactics that forced the issue into the public eye.

"Her strategy was blunt, and I think that may have prevented her from being known as the activist superstar that she really was," Loofbourow says.

Years before Roe v. Wade established the constitutional right for a woman to terminate her pregnancy, Pat Maginnis advocated for unequivocal abortion rights through a variety of direct actions.

Her position was radical at the time. As of her death in August, that position had long been mainstream.

Oklahoma and Panama

Born in 1928, Patricia Maginnis knew from a very early age that she never wanted to have children.

She was raised in a Catholic family in Oklahoma, with six siblings. Her mother never seemed to particularly enjoy motherhood — she "had many frustrations she took out" on her children, Maginnis said in a Nov. 1975 oral history interview. Maginnis also said her mother endured lifelong physical pain as a result of her pregnancies.

And so children were not part of her plan. "I don't want children," she said. "I had seen enough overpopulation, starvation and human brutality." Or, as she once told a boyfriend: "All I wanted was bed fun."

Maginnis joined the Women's Army Corps in 1951 and trained as a surgical technician. While working in an Army hospital in the Panama Canal Zone, Loofbourow says that Maginnis witnessed women injured from botched abortions, or forced to give birth when they didn't want to have the baby.

"And it was all truly horrifying for her," Loofbourow says. "And she said to me more than once — that was really the thing that radicalized her, was seeing the gamut of things that women have to go through in the name of irreversible biology that nobody lets them opt out of."

Maginnis spent three years in the Army. "It's a wonder they didn't kick me out," she said in her oral history.

Bay Area activism

She moved to California and enrolled at San Jose State College. In the early 1960s, abortion was illegal in the U.S., except when doctors granted exceptions for "therapeutic abortion" for medical conditions like psychosis or excess vomiting.

Maginnis and her cohort learned to weaponize those conditions, Loofbourow said. Maginnis and a handful of local activists would show women how to "fake the symptoms that would get them 'therapeutic abortions.'"

Still, the majority of people seeking abortions at the time did so extra-legally, according to University of Illinois history professor Leslie Reagan, who wrote When Abortion Was a Crime. And it was often a clandestine and dangerous experience.

"Women were dying every year," Maginnis told the oral history interviewer in 1975. "It left little children without mothers, husbands without wives, it was demoralizing in the extreme — and yet what was overwhelming was that people were so terrified of the word abortion."

Breaking the taboo on saying the word "abortion" became a core part of Maginnis' activism. "She made a point of actually saying the word as much as she could," Loofbourow says. "'I'm going to talk about abortion. Abortion!'"

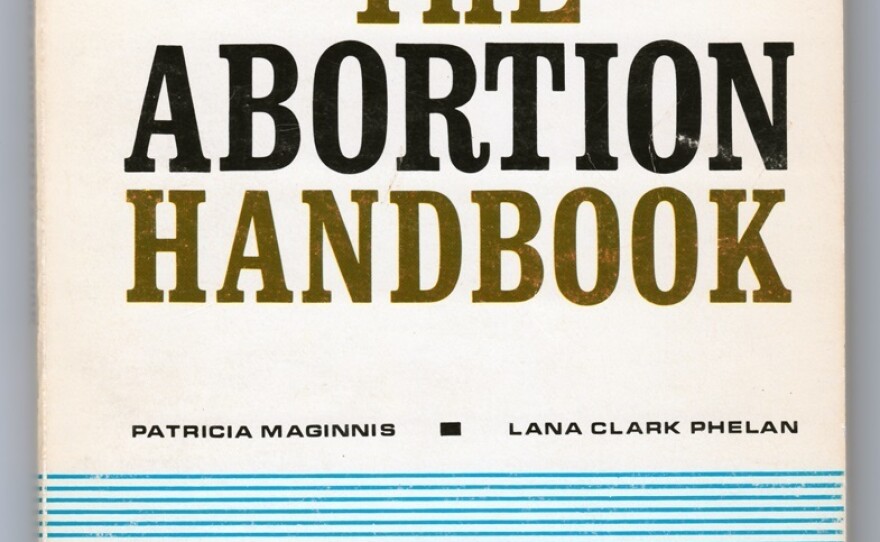

At the time, Reagan says mainstream abortion reform was driven by doctors and lawyers, mostly male, who focused on tempering legislation. Maginnis founded a group that came to be known as the Society for Humane Abortion. The SHA not only demanded the repeal of abortion laws, but ran an underground arm focused on helping women obtain abortions.

Maginnis' strategies included passing out leaflets on do-it-yourself abortions and holding classes that demonstrated techniques to induce abortion at home. These also served as ways of seeking arrest and forcing conversation on the need for safe and legal means to terminate pregnancy.

And Maginnis and her cohort also compiled a list of abortion providers outside the U.S. — "a Yelp inventory of doctors outside the country who it was safe for women to go to," Loofbourow says — and made it available to those seeking an abortion. The list contained not just names of doctors, but their fees, and descriptions of the procedure.

It even included tips for how to travel to places like Mexico. To avoid suspicious border guards, for example, the list encouraged women to buy souvenirs at the border, so they looked like ordinary tourists.

Maginnis' group monitored the list for standards of practice by asking women to fill out surveys after their procedures. At least in one occasion, that was too late — Reagan noted that one specialist had to be removed after multiple accusations of rape. The group didn't remove that person from the list until a second woman claimed the specialist had raped her.

It isn't known how many women were harmed as a result of relying on the list. But Lili Loofbourow says there's no question what Maginnis was trying to do with her activism.

"This was really the way to return power to women," Loofbourow says. "Even if it was hard, even if it was painful and even if it was scary, she thought it was crucially important to actually return some of that power to the people concerned because women had been reduced to an almost infantile state by a medical community that thought ... the authorities should be making those decisions for them."

Maginnis herself had three illegal abortions, two of which were self-induced. According to historian Leslie Reagan, Maginnis was "the first person to publicly talk about her own illegal abortions and to provide information to anyone who wanted it."

Maginnis had little concern for propriety, Reagan said. And her stance was uncompromising. "She was the first person who spoke publicly saying [that] abortion should be completely decriminalized," Reagan said.

"[Maginnis] was earlier than the movement that we know of as women's liberation. She's ahead of everybody."

Out of the SHA grew a legislative arm, the Association to Repeal Abortion Laws. ARAL was a precursor to NARAL Pro-Choice America, now one of the country's top abortion rights advocacy groups.

A legacy of letters

Toward the end of her life, Maginnis' living room served as something of an informal archive of her work. One feature that guests often commented on were the piles of letters.

"She had stacks and stacks, almost like towers, of the plastic shopping bags with letters in them," said artist Andrea Bowers.

These were the letters Maginnis had received in the 1960s from people desperate for any information on abortion — "some of the most emotional things I've ever read in my entire life," Bowers said. "Reading those letters and the pathos in them, the stories, thousands of letters both men and women wrote, who needed a safe abortion for their loved ones, for themselves, for their daughters."

With Maginnis' permission, Bowers copied these letters and preserved them in a video project called "Letters to an Army of Three." One letter came from a woman who identified as 18 years old and pregnant by a married man. She wrote to Maginnis and said: "I need the name of a doctor for I am in a desperate situation ... You are my last resort."

According to Reagan, the SHA reported sending 12,000 women outside the U.S. for abortions by 1969.

Maginnis died Aug. 30, 2021. She was 93 years old.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))