Ingrid Bergman was a so-so typist. Katharine Hepburn's signature was indecipherable. Marlene Dietrich signed her letter to Ernest Hemingway as "Your Kraut."

A collection of letters, memos, telegrams and other written communiques from the golden age of Hollywood are collected in a new book. Letters from Hollywood, edited and compiled by Barbara Hall and Rocky Lang, is a delicious peek into very famous people's private lives.

Take Audrey Hepburn. On screen, she was perfection: the bangs, the long cigarette-holder in Breakfast at Tiffany's, the lavish hat at Ascot in My Fair Lady.

In 1963, after seeing the My Fair Lady script for the first time, she wrote the director (in perfect schoolgirl penmanship) of her delight.

It's MARVELLOUS, I am beyond myself with happiness and excitement! It is all so good and so solid, warm funny and enchanting. I just pray every day to be as good as the role, or is that too much to ask for? All the wonder of the musical and the play are there, it's just smashing!

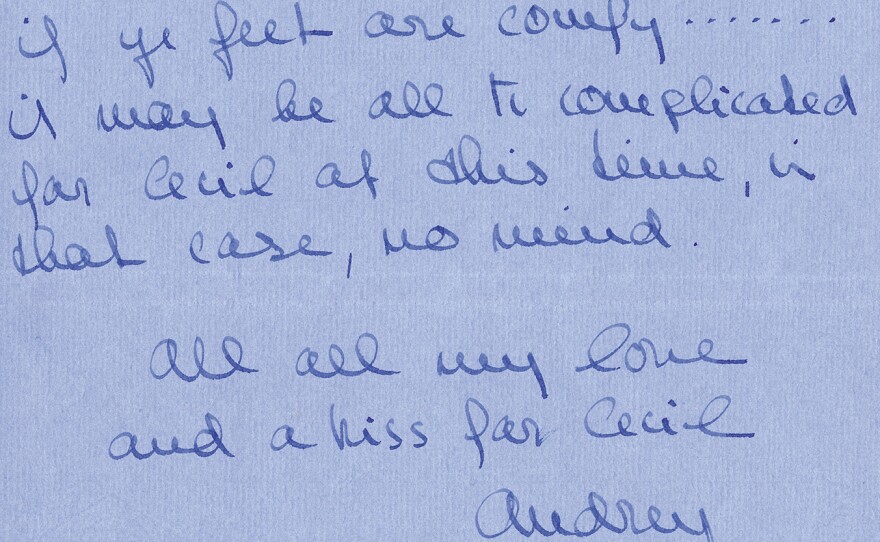

But perfect Audrey, it seems, had bad feet. Hepburn asks for the designer's sketches of her shoes so that her private bootmaker in Paris can cobble them for the movie.

One is an awful lot on ones feet when working — and since my days in the ballet I have had "trouble with me feet" unless properly "shoed." ... It does make all the difference.

"I think it's the kind of thing that it's great to learn about an actress," co-author and film historian Barbara Hall says. "We think of them — sort of put them on a pedestal, but really, she was a regular person, and obviously a very charming one."

In other words, she was a great star who knew what she needed to do her best work.

Bette Davis was also like that. A winner of two Oscars, she's famous for the immortal line from All About Eve: "Fasten your seatbelts. It's going to be a bumpy night."

Years before Eve, Bette Davis was exhausted, overworked. Hollywood studios controlled their actors in those days, and there was little rest for Warner Brothers' biggest star.

"They just kept putting her in more and more films," Hall says. "And she felt like she needed more time between projects."

Davis wanted to make fewer pictures every year — more time off between movies. So she wrote (again, by hand) to studio head Jack Warner, protesting her contract. She ended her very firm letter:

Would appreciate your not communicating with me — it upsets me very much. I must be allowed to completely forget business. ... Also arguing with me is no use — nor do I want to come back until it is settled --

Another letter-writer in this collection is Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to win an Oscar (for best supporting actress) as Mammy in 1939's Gone with the Wind.

McDaniel was a busy actor in the 1930s and '40s — always playing a maid or servant. In 1947, she thanked gossip columnist Hedda Hopper for printing kind words about her. But others criticized her for taking so many servant roles. McDaniel wrote:

Truly, a maid or butler in real life is making an honest dollar, just as we are on the screen. I only hope that producers will give us Negro actors and actresses more roles, even if there will be those who call us Uncle Toms.

The NAACP and other civil rights organizations had started pressuring studios to get rid of stereotypical roles like McDaniel was playing — the only parts African Americans could get then. The protests had a bitter result for the Oscar-winner: Hattie McDaniel found that she was getting fewer and fewer roles in the immediate postwar years, because they weren't being written.

Among the 137 items in this book is a telegram to director William Wyler, sent in 1937 by an extremely precocious star-to-be.

I ADMIRE YOUR PICTURES AND WOULD LIKE TO WORK FOR YOU I AM EIGHTEEN MINUTES OLD BLONDE HAIR BLUE EYES WEIGHT EIGHT POUNDS, AND I HAVE BEEN CALLED BEAUTIFUL MY FATHER WAS AN ACTOR=

JAYNE SEYMOUR FONDA.

The real author of the telegram was Henry Fonda — Jane Fonda's father. So in his reply to the new baby, Wyler wrote that he wanted to make a screen test of her as soon as possible. But he also took a playful shot at her dad: "WE FEEL IT OUR DUTY TO CORRECT ANY ILLUSION YOU MAY HAVE BEEN UNDER IN THE PAST ... YOUR FATHER NEVER WAS AN ACTOR."

Letters from Hollywood is subtitled Inside the Private World of Classic American Moviemaking. These are very personal letters from stars, directors, heads of studios. So is it an invasion of privacy to publish them?

"I don't think so," says Peter Bogdanovich, the director, writer, actor, film historian and author of the book's foreword. "It's history."

Nina Gregory edited this story for broadcast.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))