This year saw the largest outbreak of measles in the U.S. since 1994, with 1,250 cases reported as of Oct. 3, largely driven by families choosing not to vaccinate their kids. Worldwide, the disease has resurfaced in areas that had been declared measles-free.

Some families choosing not to vaccinate argue that measles is just a pesky childhood illness to be endured. But two new studies illustrate how skipping the measles vaccine carries a double risk. Not only does it leave a child vulnerable to a highly contagious disease, but also, for individuals who survive an initial measles attack, the virus increases their vulnerability to all kinds of other infections for months — possibly even years — after they recover.

The research begins to explain something surprising that happened when the measles vaccine was introduced in the U.S. in the 1960s. Rates of childhood deaths from other diseases fell precipitously. The same thing happened as the vaccine was introduced around the world.

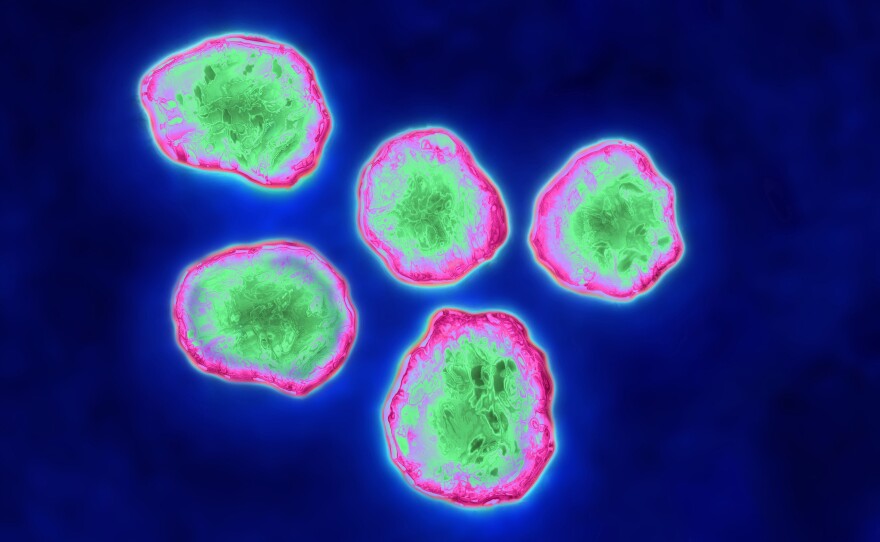

But what is it about the measles vaccine that seems to provide protection from more than just measles? The new studies published this week in the journals Science and Science Immunology provide substance to what has been the leading theory: Measles can damage the immune system by erasing the body's memory of previously encountered antigens.

One of the key features of our immune system is that it keeps track of the infectious agents we've encountered and uses that memory to prevent reinfection. But after someone gets the measles, their immune system appears to forget some of what it has encountered, studies suggest. It's an effect researchers refer to as "immune amnesia."

Previous evidence for immune amnesia has been based on mathematical models and population-level studies according to Dr. Michael Mina, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the primary author of the study released this week in Science. The new studies are the first to show "any of the real biology that helps explain the population-level effects," he says.

"Understanding how this happens has really been a burning question," says Dr. Duane Wesemann of Harvard Medical School. Wesemann authored an article in Science Immunology explaining the significance of both studies; he was not involved in either. "These two papers complement each other in an interesting way, and they both provide clues to help answer how measles causes immune damage."

The two studies used blood samples collected from 77 unvaccinated children in an Orthodox Protestant community in the Netherlands, before and after the children contracted the measles virus during a local outbreak. Parents in that community do not vaccinate on religious grounds but were willing to participate in a research study about the virus. The studies each investigated different branches of the immune system, and both found evidence to support the immune amnesia hypothesis.

"Even coming into this with a pre-existing hypothesis, the findings that we've made here are much more striking than we could have expected," says Mina.

The Science Immunology study released Thursday investigated whether the character of the immune system changed after measles exposure. The researchers sequenced the genes of immune memory cells and found that after recovering from measles, the children's immune system had a different landscape of certain types of cells.

"The immune cells that normally would recognize new pathogens — they become restricted in their ability to respond" after recovering from measles, says Velislava Petrova of the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the lead author of the Science Immunology paper.

"What was interesting is that we can recover our normal cell counts, but we're still immunosuppressed," she says.

To confirm that the decrease in cell diversity would translate into a weaker immune response, Petrova's team conducted an experiment in ferrets. They vaccinated a group of ferrets for the flu, exposed some of them to a measleslike virus, then tested to see whether the flu vaccine still worked. As expected, they found that the ferrets that had had measles were more susceptible to the flu than the control group.

The Science paper looked at the diversity of antibodies in the bloodstream using a new technique called VirScan. "This method allows you to — just from a drop of blood — detect your whole history of viral infection, looking at thousands of antibodies and their targets at one time," says Stephen Elledge of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, who was the study's principal investigator.

What they found was that after measles, previously healthy kids lost on average about half — and as much as 73% — of their overall antibody diversity. Or, as Mina puts it, "measles seems to be punching holes in the immune memory."

"The real takeaway is that underneath the surface, measles is much more than a rash, and it's much more than just an acute viral infection. It's got these very long-term, stealthlike detrimental effects that are extraordinarily difficult to measure," says Mina. "We've been able to show that the effects are vast and impact almost all pathogens that somebody has seen."

Wesemann highlights the Science paper's finding that people who had gotten the measles vaccine showed increased immune strength. "You get the best of both worlds with the vaccine," Wesemann says. "You get the robust immunity against measles virus without having to be infected with it, but it doesn't cause the immune damage that the real measles virus causes."

"The measles vaccine is really a superhero," he says.

Elledge says that for parents who may be wavering on the edge of a vaccine decision, they can think of the measles vaccine "like a seat belt for your immune system."

"We know that seat belts protect against head injuries that can cause amnesia. The measles virus is like an accident too — it can give you immune amnesia. Think of the measles like an accident you can prevent in a parallel way," he says.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.