Rosarito-born artist Hugo Crosthwaite said being on a White House list of “divisive” Smithsonian exhibits feels like a “badge of honor,” but warns the risks of governmental control of art are real.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration announced a review of all Smithsonian museums, to, quote, "celebrate American exceptionalism" and "remove divisive or partisan narratives." The four-page letter, calling for the review, outlines a detailed, multi-phase plan and timeline. This includes reviews of staffing, projects, future plans, educational materials, external partnerships and grants, as well as a catalog of all current exhibition content and permanent collection holdings.

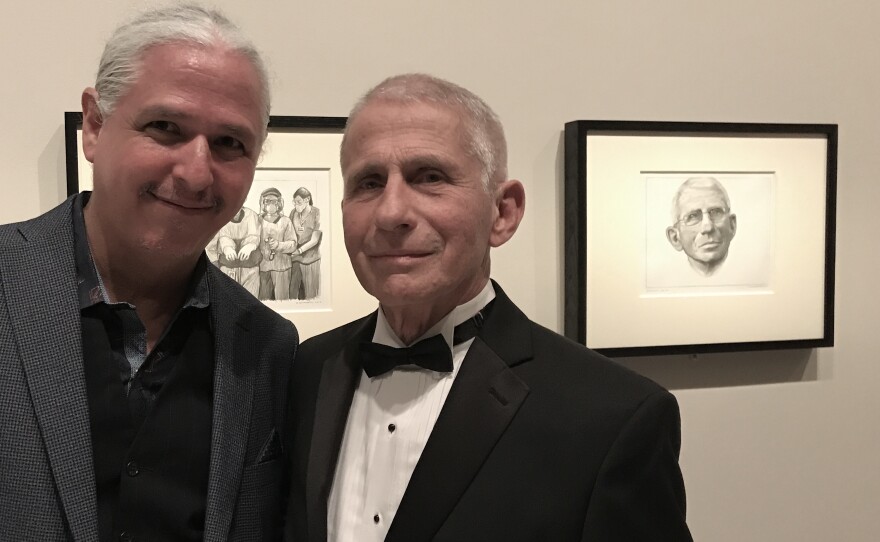

Days later, the White House posted an article titled "President Trump Is Right About the Smithsonian," listing works and programs focused on race, immigration and sexuality — including Crosthwaite’s stop-motion portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) and chief medical advisor to President Joe Biden.

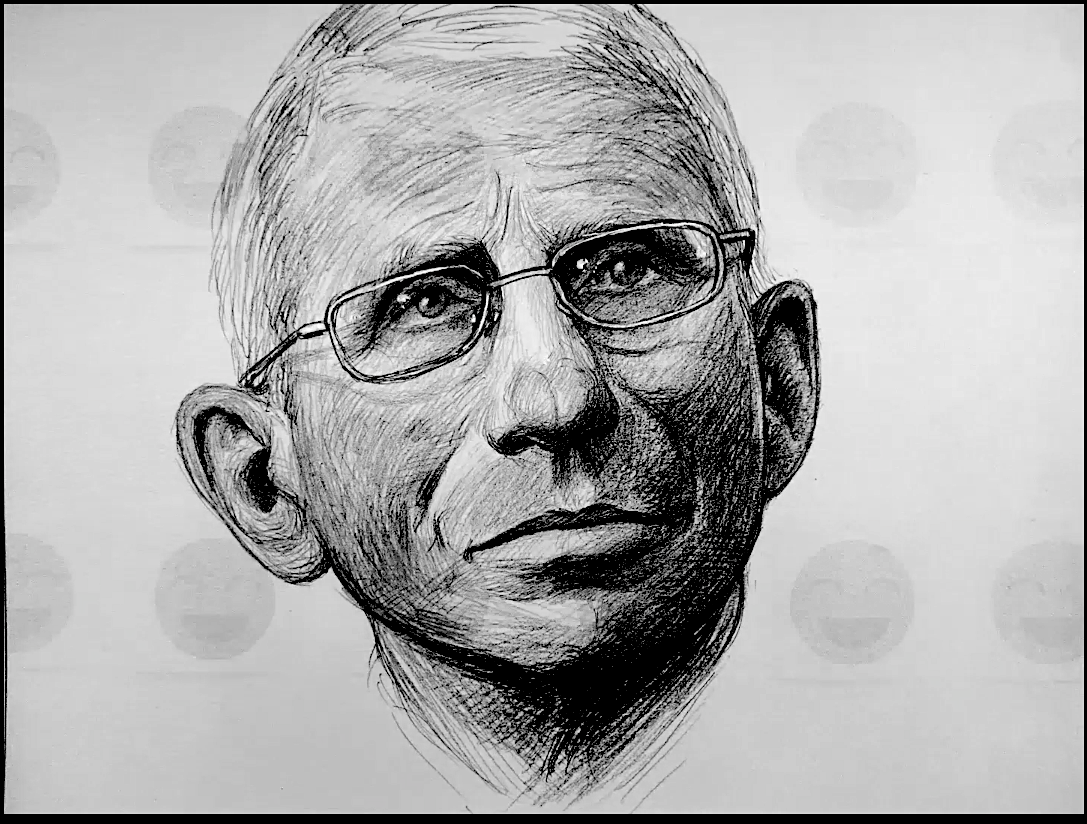

The piece, commissioned by the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and unveiled in 2022, chronicles Fauci’s decades-long career through intricate, vivid sketches, spanning the HIV/AIDS epidemic to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the time of publication, the White House had not responded to requests for comment on why Crosthwaite’s work and others were included.

Below are highlights from KPBS Midday Edition’s interview with Crosthwaite. Responses have been edited for clarity and conciseness.

On history in portraits

I won the first prize in the 2019 Outwin Boochever portrait competition, and as part of that prize that's given by the Smithsonian, I had the opportunity to create an official portrait commission for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

The museum proposed that I should make a portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, and because the COVID-19 pandemic was happening at the time, I jumped at the chance to do this. I wanted not just to do a portrait of a person, but also capture that moment in history — through the pandemic — as a stop-motion drawing animation.

I envisioned that the portrait itself would be a biography of Dr. Fauci's career, but him inside of history, of that moment in history that we're living. So then it would be Fauci's career and it would be him intermixed with social history and images of magnified viruses. So then after meeting with Dr. Fauci, we came up with this narrative that we developed together. And at the end, it became this 5-minute stop-motion drawing animation composed of a suite of 19 drawings.

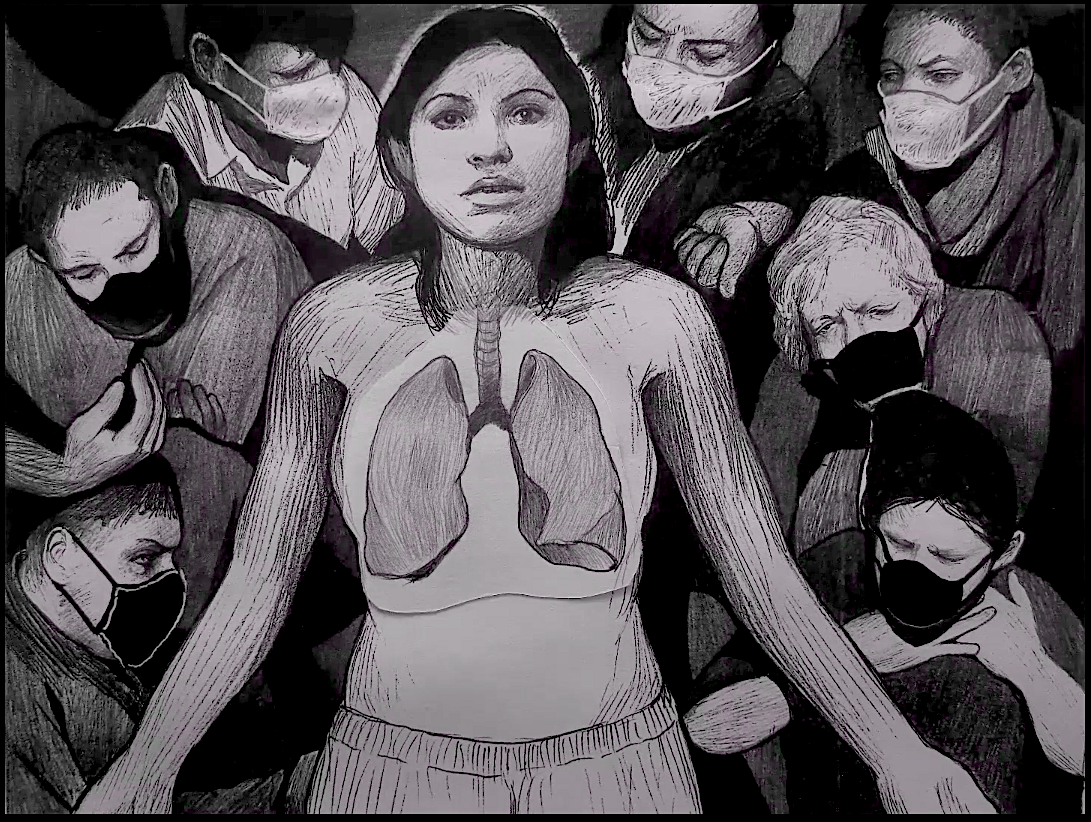

The animation itself draws images from scientific illustration, popular culture, media images and art historical references that create a portrait of Dr. Fauci that speaks not only to the career of him as a scientist and public servant, and then also his management of two of the gravest health crises that happened to the United States: the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic.

It points to the politics of the era where the government and the health policies weren't seeing eye-to-eye, so it kind of captures those two moments of history and they echo each other.

The artwork moves through four decades of recent history, shedding light on the social strife that was caused by these two health crises.

It points to the politics of the era where the government and the health policies weren't seeing eye-to-eye, so it kind of captures those two moments of history and they echo each other.— Hugo Crosthwaite

On Fauci's evolution

During the AIDS epidemic, the Reagan administration wouldn't even mention the word AIDS or wouldn't even acknowledge the gay community.

That was basically the problem. The government was not getting involved with this horrible disease. So there was that moment in history where Dr. Fauci met with the LGBTQ community in Brooklyn, the ACT UP movement that was happening. They were protesting that the government needed to listen to them and give them medicines and start programs. Dr. Fauci actually met with this organization and that started the dialogue — and he did this in a personal way, not as an official coming from the White House, but he himself going to these meetings.

At the beginning, he was being vilified by the gay community, but at the end, he earned the respect because he was an official who came down from the Reagan administration to talk to them and to see what they needed. That was a very important element to it. And of course, he learned this; he's a scientist, he's involved with these programs, but also he saw the importance of this communication that needs to happen between a government and its people.

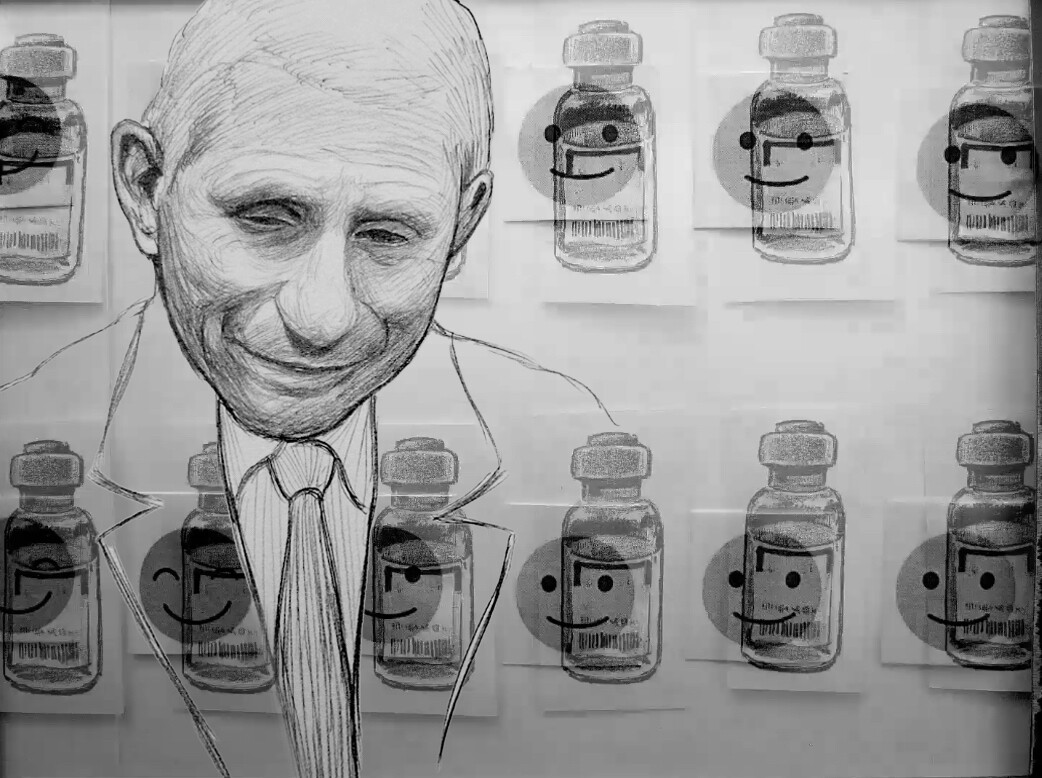

And then of course the opposite happened with the COVID-19 pandemic, where I feel like it was more of a public rejection of the government programs that were coming in to help with this pandemic — especially, you know, those conspiracy theories that were being given about the vaccine itself.

On stop-motion as portraiture

Well, I'm not a very good portrait artist. I always feel like when I draw a person and I show them my drawing, they always complain that they don't look like that drawing. So, in a way, I don't feel strong in that medium, as a portrait artist. As a way of working around that dilemma, I thought that the portrait could be this idea of a narrative, of a story, the idea of a story becoming the portrait — one's actions, one's life, that would be the portrait. And it describes this moment in history.

I remember when I spoke with Dr. Fauci; he's a very humble man. So when he knew that the National Portrait Gallery wanted to commission a portrait, he was kind of hesitant. He said so directly to me, "I don't want a big portrait of me in a painting." But when I came up with this idea, you know, it's not going to be that. It's going to be this narrative. It's going to be this animation that tells a story through history and all this. He loved that idea because, to him, he mentioned to me that it's me placing him in history and not just standing him out of history in a portrait that's basically just exalting a person. It's more of him inside this moment of history. He thought it was a very innovative idea of presenting his life and his career as this stop-motion animation.

Through film, through animation, you can put a lot of other dimensions into it, not just the likeness of the person. I love playing with comedic elements in it and then it goes into some horror kind of things. In the beginning, the animation starts as if it were a public service announcement or a corporate video about creating vaccines. But then it evolves into the story, a very human story of how viruses and diseases attack our population and all the suffering that happens. Also, how the medical establishments — doctors, scientists — fight this through science and through coming up with vaccines and cures. So it plays with this very human narrative, how the disease can affect the population and then how we respond to it with fear, we respond to it with conspiracy theories or we also respond to it with valor and strength from the first responders and the nursing and doctors communities who risk their lives to save us.

On U.S. public health

I feel the United States doesn't have a good healthcare system, in the sense of it being funded or it being accessible to people. Being one of the richest countries in the world, it should have good socialized medicine in a way to help the population, and they don't. It's all very corporate. My experience has been that I don't have access to healthcare, which is a shame, especially coming from the United States, which has the money to do it, but they just don't.

My experience has been that I don't have access to healthcare, which is a shame especially coming from the United States, which has the money to do it, but they just don't.Hugo Crosthwaite

On Smithsonian recognition

To me, it was a great honor because it was actually being part of American history. The National Portrait Gallery is a museum that has the portraits of all the major characters, heroes, persons from history, from George Washington to Benjamin Franklin to all the presidents and all the incredible people — it's American history, and I was able to have one of my pieces be part of that telling of American history. So to me, it was a great honor to be on the record. I'm part of American history now through my portrait of Dr. Fauci.

On the meaning of 'national'

It's this idea of trying to rewrite history, trying to erase our diverse experiences, our diverse history. They want the general public to forget the ills of our past, and to follow an agenda that is not based on the realities of the United States, of our nation. And the danger of that, of course, is that we're condemned to repeat terrible mistakes.Hugo Crosthwaite

It just means being part of the United States, and the pride of being part of a great nation with great people with a great history. It's had its ills, it's had its problems, but I feel that the United States is an ideal — that it's recorded in the Declaration of Independence or the Bill of Rights, that all men are created equal. Those are ideas that I strongly believe in, and that we need to fight for. And we're living in a moment where they're trying to erase history. That's part of what's happening right now with all this, with this list of art that's being reviewed. It's this idea of trying to rewrite history, trying to erase our diverse experiences, our diverse history. They want the general public to forget the ills of our past, and to follow an agenda that is not based on the realities of the United States, of our nation. And the danger of that, of course, is that we're condemned to repeat terrible mistakes if we don't look objectively at our history. So to me, national is that I take pride in my nation, the United States, and I don't want that history to be erased.

On the White House list

When I actually went to the website and I saw the list, I felt a kind of pride that I was in the list of wonderful art projects. I saw it as a badge of honor to be in this list of artworks and art pieces from artists that I admire. So yeah, at first I was like, "Well, yeah, this is not bad to be included in this list."

Of course, like everything with this administration, they're trying to instill fear in the public, and I'm not going to give in to that. I'm not going to give in to the fear that they're trying to inspire, so I'm going to keep working. I'm going to keep doing what I need to do. Art is not a profession; it's a vocation. I feel very strongly about what I paint, what I draw, the subject matters that I deal with, and I'm going to continue that despite any list or any review.

I'm not going to give into the fear that they're trying to inspire, so I'm going to keep working. I'm going to keep doing what I need to do. Art is not a profession, it's a vocation.Hugo Crosthwaite

On why his work was called out

Well, it was funny to me because when I saw the list, it didn't really describe the piece. It just mentioned there was this commission about this portrait of Dr. Fauci's career. So I got the feeling that even the Trump administration hasn't even seen the portrait, because they didn't mention any of the other things that could be considered controversial inside the film itself, where I show imagery of protests and things. It seemed to me like they just saw, "Oh this is about Fauci" then, "We hate it." I think they targeted the piece precisely because it's just a portrait of Dr. Fauci being a public servant who has diligently, heroically served his nation for more than 50 years. He's regarded with the highest esteem in the scientific community, but then also he's been vilified by the MAGA movement and in conspiracy theories. So then I think that Dr. Fauci just became the symbol more than a man, he became this focus of conspiracy theories and he kind of represents the nation's current political divide. So I think that would be the reason that they think Fauci is a danger, because he represents truth, he represents science.

I'm a Mexican-American artist, so someone who's cognizant of the impact that AIDS and the COVID-19 pandemic have had on my ethnic community. At this moment, the critical social and health programs are being defunded by the Trump administration, and that's something that the White House is trying to gloss over — how their policies are affecting the most vulnerable people in the United States. But I don't know if that's the reason why.

On art and government control

This is the first time that my work has ever been put on a list or up for review. I've had the fortune that whatever I do has always been accepted by institutions and shown, celebrated, and presented. And I always feel, for me, as an artist, I feel that that's one of the virtues of art, the eloquence and the beauty of drawing and painting. You can handle any subject matter, how it doesn't matter how controversial it can be, but if it's done in an eloquent way, people are open to it — because they come to a beautiful drawing, they come to a beautiful story, and they see it and they're able to accept it. They might not agree with the subject matter, but they come to see a beautiful drawing and a beautiful painting.

I think that's one of the virtues of art itself. You know, we're not journalists. We're not there to tell the truth and give hard facts. Like Picasso said — I think I'm misquoting him — but he said something in reference to how art is the big lie in the service of truth. This very idea that yes, it's a very subjective way of presenting the truth. But then that's the virtue of art, that we can lie and we can exaggerate things and we can present things to the public in a beautiful way. That's what art is.

I feel like these are all distractions. These are all creating these controversies from this administration, because there are actually real problems that need to be dealt with, and they're trying to steer the public's attention away from some real issues. They're drumming up these fake controversies or these dilemmas.

On what's at stake

At risk is this idea of trying to rewrite history, trying to have people forget the problems, the ills, the what needs to be solved. I think that's their intent. And then that's the danger that people actually do forget. If these institutions don't tell our story and don't educate us to what's happened and be objective in our history and all this, people will forget and we will repeat the mistakes of the past. That's a danger of it.

I feel like there's also the silver lining. For example, this list drew more attention to the work. I'm getting attention for the work. So, in a way, I think it's kind of counterproductive for them. I think it's backfiring to them, this idea that they try to censor work and by doing that it just is drawing more attention to it. And it's drawing more attention to the subject matter and to the issues and the truths that need to be out there.

On artists as social critics

Art is a vocation, and we say what we need to say — and we say the best way we can. The problem when this happens is that they're trying to install fear in people and fear in artists, so then we — sometimes — we even start censoring ourselves. I think that's the danger that will definitely harm the art that we're creating. We need to be strong, we need to believe in who we are. We're artists and we have this vocation. And then, of course, nothing is forever; no ill lasts a thousand years. This time will pass, this moment will pass, and those people who stay true to their vocation and stay true to the truth — the truth will win in the end. I feel that always happens, so just believe in your work and continue to work.

There are lots of moments in history when this has happened ... the Exhibition of Degenerate Art that the Nazis put together back in the 1930s, where they were kind of showing this artwork that was against the regime's ideas of beauty and that went against their propaganda. It was an exhibition of these wonderful artists from Picasso to Cézanne to Kandinsky and Max Beckmann — and that exhibition drew more attention to these artists.Hugo Crosthwaite

There are lots of moments in history when this has happened. Some artists have mentioned this idea of how — they call it the Exhibition of Degenerate Art that the Nazis put together back in the 1930s, where they were kind of showing this artwork that was against the regime's ideas of beauty and that went against their propaganda. But it was an exhibition of these wonderful artists from Picasso to Cézanne to Kandinsky and Max Beckmann — and that exhibition drew more attention to these artists.

When they try to censor something, it draws more attention to it, and I think that's great. That's wonderful. I think more people are going to see my portrait now more than ever.

In San Diego, Hugo Crosthwaite’s work includes a public mural at Liberty Station's Barracks 14, 2770 Historic Decatur Road.