Luis was a lawyer from South America who ended up homeless in San Diego.

He arrived in August 2024, at the tail end of a historically high migration period. In just a few years, hundreds of thousands of migrants from all over the world had crossed the border in San Diego to pursue asylum claims. There were so many that Border Patrol agents would drop off busloads of people at a San Ysidro transit center every day.

“I remember meeting Luis for the first time getting off one of the buses,” said Ruth Mendez, an immigrant advocate with the Detention Resistance Collective.

Luis is seeking asylum as a political dissident in his home country. KPBS is not disclosing his last name to protect him from retaliation.

By the time Luis got off the bus that day, San Diego County had closed its emergency migrant shelter. The private contractor selected to run the program ran out of money.

He ended up spending 10 days sleeping on the floor at San Diego International Airport before he found temporary housing at a local Catholic church.

Luis is still here today, with a more stable housing situation. His year-long case spans one of the most uncertain times in the history of the U.S. asylum system.

He arrived last summer, two months after the Biden administration bowed to political pressure by placing strict limits on asylum. And his case remains ongoing after the Trump administration began arresting people in immigration court hearings.

Have a tip? 📨

The Investigations Team at KPBS holds powerful people and institutions accountable. But we can’t do it alone — we depend on tips from the public to point us in the right direction. There are two ways to contact the I-Team.

For general tips, you can send an email to investigations@kpbs.org.

If you need more security, you can send anonymous tips or share documents via our secure Signal account at 619-594-8177.

To learn more about how we use Signal and other privacy protections, click here.

“They have peeled back the rights of asylum seekers like an onion,” said Melissa Crow, director of litigation for the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies (CGRS), which has sued both administrations over their restrictive immigration policies.

One of those policies was Biden’s Circumvention of Lawful Pathways, which established that anyone who crossed the border illegally, like Luis did, would be presumed ineligible for asylum.

Previously, everyone in the country had equal access to the asylum system, no matter how they entered.

That meant people like Luis would have to navigate legal loopholes to obtain an exemption and establish eligibility. Or pursue other forms of humanitarian relief that are much more difficult to obtain, Crow said.

Then, CGRS sued over one of President Donald Trump’s first executive orders. Among other things, it terminated humanitarian parole programs, further restricted the asylum system and ordered the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to detain every migrant who crossed the border illegally.

“The restrictions we’ve been talking about — the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways rule and the Securing the Border rule — in most cases take asylum off the table,” Crow said.

Fortunately for Luis, he entered the country before Trump’s crackdown. So he was able to pursue a political asylum claim under Biden’s restrictions.

A helping hand

Despite his own precarious housing situation, Luis wanted to use his own experiences in the system to help others. He kept returning to the San Ysidro transit center where CBP agents dropped off confused migrants. He offered to help the volunteers in exchange for a free lunch.

Luis’ presence gave Mendez and other advocates instant credibility among people wary of strangers, she said.

“He could tell people, ‘Hey, I was in your position. These folks can be trusted,’” she said.

Luis spent the end of 2024 preparing for his asylum case.

Back home, he was a vocal critic of the government and feared retribution for his political beliefs. Luis left behind his relatives, his son and his legal career.

The fears that prompted Luis to flee have been with him his entire life.

“My own father was disappeared for his political views,” he said in Spanish. “So I didn’t want that history to repeat itself with me and my son.”

Courthouse arrest

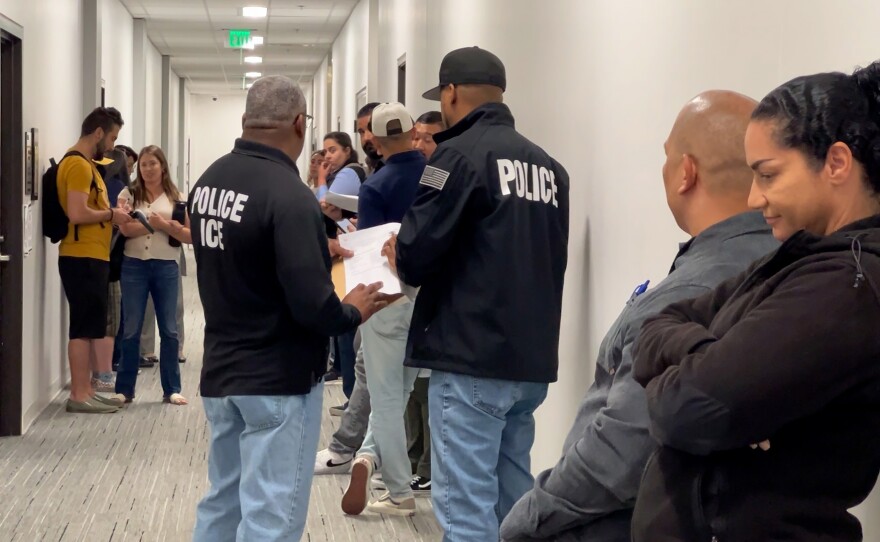

By the time Luis got to see a judge this spring, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents were arresting people in immigration courts across the country.

The White House demanded ICE arrest 3,000 people each day nationwide and courts became a convenient place for agents to meet their quotas.

Mendez and other immigrant advocates were worried about this happening in San Diego. So they accompanied migrants to their court hearings. Their fear turned out to be well-founded.

“At the beginning of that week, we heard of L.A. immigration court, San Francisco immigration court having ICE in the courtroom,” Mendez said. “That was very worrying.”

Luis and Mendez didn’t notice any ICE agents in the courtroom when they arrived for his hearing the morning of March 22.

But when he left the courtroom to use the restroom, Luis saw the hallway was full of ICE agents. He quickly shut the door, went back into the courtroom and mentally prepared himself to be arrested.

Mendez remembers him shaking while sitting in the courtroom.

The lawyer in Luis remembers thinking how odd this was. The federal government was acting as if it didn’t want people to show up for court appearances.

“It removes a lot of credibility from the process,” he said. “Why should we do things correctly, the right way, if we are going to be arrested?”

Luis was among the first to be arrested in San Diego’s immigration court. As soon as the arrests began, advocates like Mendez called local immigration lawyers for help. Several lawyers rushed to the courthouse and offered pro-bono legal services to anyone being targeted by ICE. That’s how Tracey Crowley met Luis.

She was blown away by how well-prepared he was for an asylum case — he had filed all of the paperwork by himself at that point. But that was still not enough to keep him out of detention.

“He’s doing everything he’s supposed to do,” Crowley said. “He’s trying to do it the legal way, and he actually has a really strong case for asylum. It’s just a waste of money and a waste of everyone’s time to throw him into detention.”

Life in detention

Because of his personal family history with government-sanctioned disappearance, Luis was particularly traumatized during his stay at the Otay Mesa Detention Center. He said guards would constantly pressure detainees, particularly the ones who had been there longest, to sign “Voluntary Departure” papers to abandon their cases and self-deport.

He developed a skin infection and would often fall asleep to the sound of other detainees crying. He remembers his time at the private detention center as a mindless routine of eating, sleeping and waiting.

“I felt like a robot,” he said.

Despite having a relatively strong political asylum case, Luis often thought about giving up.

“It was very difficult to keep his spirits up, and to keep him motivated because I knew I could get him out on bond,” Crowley said.

After about six weeks, Crowley was able to secure Luis' release on bond. Luis described his release as “winning the lottery.”

Within days of his release, Luis started volunteering again. This time outside of the same immigration court where he was arrested months earlier. Mendez said he’s been an invaluable resource to the volunteers, especially when anxious families of people in immigration court ask for help.

“He just steps in and tells them what to expect,” Mendez said. “That type of information that advocates can relay, but it hits differently when it’s somebody who was directly impacted.”

Luis is still pursuing an asylum claim and is due back in court next month. Mendez, Crowley, and other volunteers plan to accompany him.